Source: “2019 Corridor Performance Report for the I-66 Inside the Beltway and I-395 Corridors,” presented March 5, 2020.

by James A. Bacon

In late 2017, the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) installed tolled express lanes on the congested inside-the-Beltway segment of Interstate 66. Planners hoped the tolls would discourage commuters from driving solo, and surplus toll revenues would be used to expand bus and rail alternatives. There was a frenzy of media coverage in the early days when dynamically set toll prices pushed past $47 for an inbound rush-hour commute, but the fever soon abated.

The Northern Virginia Transportation Commission (NVTC) decided to revisit the issue two years later. A new study has concluded that I-66 inside the Beltway “moved people more efficiently” in 2019 than it did in 2015 before the tolls were installed.

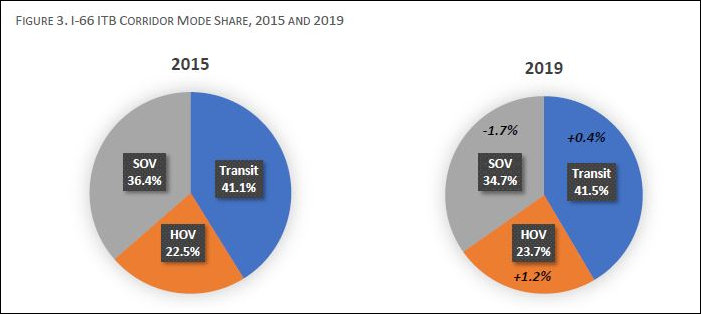

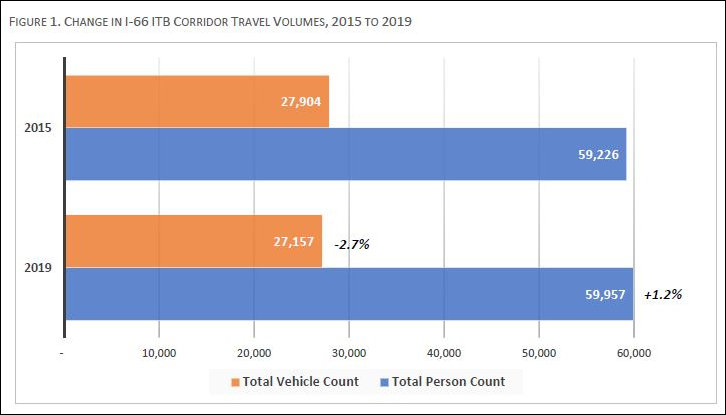

The total number of people traveling inbound during morning rush hour increased by 1.2% while the associated number of vehicles decreased by 2.7%, indicating a shift in the share of trips made by transit and HOV. Overall, 65% of the corridor’s morning rush-hour inbound trips were made by transit or HOV in early 2019, compared to 64% in early 2016.

While the traffic trends budged in a positive direction, the change was incremental. Despite incentives created by the tolls to switch, commuting patterns remain largely the same, as can be seen in the graph above.

The limited change in commuting patterns that has occurred has consisted mainly of people shifting from solo driving (single occupancy vehicles, or SOVs) to shared vehicles and mass transit. HOV (high-occupancy vehicles) has gained 1.2 percentage points of market share, while bus and mass transit have gained o.4 percentage points of market share.

The state has been reinvesting most of its toll revenues in mass transit, particularly commuter bus. (The study provides no dollar figures, so it is difficult to gauge the magnitude of that investment.) Rail has increased its share of transit ridership slightly, from 82.5% to 82.8%, while commuter bus has climbed from 9.3% to 11.4%. At the same time, the local bus share of transit ridership has declined from 8.2% to 5.8%.

The NVTC study asked an important question: Does the investment in commuter bus complete Metrorail or steal passengers from Metrorail? If the program was just spurring riders to switch from one mass-transit mode to another, the investment would be of questionable value. However, the study concluded, “Commuter bus services are not taking riders away from Metrorail. Rather, commuter bus services and Metrorail are serving different markets, and both have enjoyed ridership gains over the last two years.”

Bacon’s bottom line: This analysis is welcome. The study answers questions that the NVTC and VDOT need to be asking. But it seems curiously deficient. It does not reveal how much money the inside-the-Beltway tolls have raised, nor how much has been invested in transportation options. Thus, we have no way to determine if they money is being well spent. The reality could be like the old joke:

Wife: “Honey, I saved a $100 buying these new shoes on sale!”

Husband: How much did they cost?

Wife: Oh, five hundred dollars.

Husband: smacks forehead.

Still, overall, the tolls do seem to be working as advertised. Across the Washington metropolitan region, traffic congestion is getting worse, not better. By contrast, it is improving incrementally inside the Beltway. That’s saying something.