by James A. Bacon

If you’re looking for a good Sunday read, consider an article by Tim Sablik, “Has the Pandemic Changed Cities Forever?“, in the Richmond Federal Reserve Bank’s Econ Focus. Sablik does a fine job of sketching out the big issues identified by the nation’s leading urbanologists as they ponder the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on urban development.

In a nutshell, Sablik argues that (a) the epidemic has clobbered the urban cores of American metros as knowledge workers have drastically changed their work habits and personal preferences, (b) that the pendulum will swing back partially as the epidemic subsides, but that (c) things will not go back to the way they were. There are profound implications for cities and counties in Virginia as they plot their futures. Reading Sablik essay is a good place to start any re-evaluation.

Before COVID-19 struck, the prevailing wisdom was that the “economics of agglomeration” gave large metropolitan statistical areas — and core urban areas within the the MSAs — a tremendous competitive advantage. From start-ups to Fortune 500 companies, corporations gravitated to metros with the largest, deepest, most skilled labor pools. This powerful economic advantage overcame the disadvantage of higher taxes and cost of business, floundering schools, and higher crime rates..

But COVID-19 introduced a new dynamic, actually, an ancient dynamic that public health measures of the past century had held in abeyance: fear of disease.

Throughout history, cities have been associated with epidemics, from the Black Death in the Middle Ages to cholera outbreaks in the industrial revolution. “There are demons that come with density, the most terrible of which is contagious disease,” Sablik quotes Harvard University’s Edward Glaeser as saying. Advances in sanitation and medication took that factor off the table for decades. Then COVID-19 reintroduced it.

Moreover, COVID-19 coincided with a technological revolution that made it possible for a large swath of the workforce to work from home. Writes Sablik:

“We know from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ American Time Use Survey that before the pandemic, 5 percent of working days were done from home, says [Nicolas Bloom of Stanford University]. “During the pandemic, the share of working days from home jumped to over 50 percent.

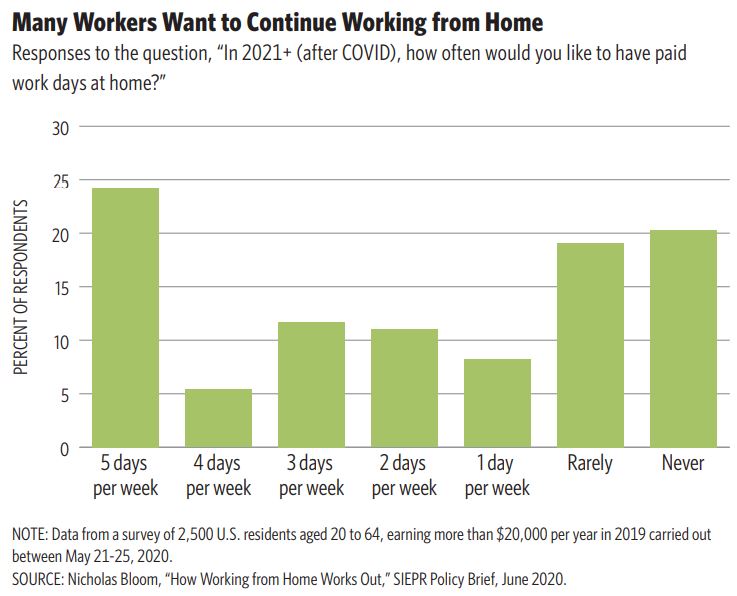

But this tenfold increase didn’t affect all workers evenly. In a survey of 2,500 workers Bloom conducted last May, about a third said they could do their jobs perfectly from home, while another 30 percent said the couldn’t their job from home at all.

This divide is starkest in cities.

The pandemic-related shutdowns of places of business had a secondary effect.

Bars and restaurants curtailed in-person seating to comply with social distancing guidelines. Theaters and museums closed. Sporting events played out for TV audiences and empty stadiums. As the lockdowns stretched on, some began to wonder whether people who could no work from anywhere would choose to stay.

In numerous surveys, a majority of workers have expressed a desire to continue working from home at least some of the time when the pandemic ends. Both workers and firms made investments in physical and human capital to support working from home, such as purchasing home office equipment and upgrading servers. Meanwhile, people have developed new habits such as exercising on their Peletons and binging on Netflix rather than frequenting the gym or movie theater. “The pandemic has basically accelerated 25 years of telework growth into one year,” says Bloom.

Sablik acknowledges that there is a pent-up demand for social interaction, especially among young people, and he does expect a partial return to the status quo ante. Still, he speculates that some businesses many opt for cheaper locations, perhaps in scenic natural settings or with higher-performing school systems. I think cities like New York are more vulnerable than they have been in decades,” he quotes Glaeser as saying.

Bacon’s bottom line: Sablik highlights the major issues that urbanologists are wrestling with regarding the impact of COVID-19. His focus in the article is COVID-19, and he sticks faithfully to that theme. But COVID is only part of the story. The viral epidemic coincided with another kind of epidemic — the wave of radicalism that coincided with the police killing of George Floyd. To some (perhaps unknowable) degree, the unemployment spike engendered by the COVID-19 shutdowns fed the street protests calling for racial justice, engendering a wave of violence in many cities.

Parts of the U.S. are becoming increasingly ungovernable. As many cities and states experiment with efforts to end mass incarceration by emptying jails and prison, violent crime rates are on the rise. Parallel efforts to create “equity” in schools have combined with COVID-driven school closures to create even greater racial disparities in academic achievement than existed before. Social anarchy, violent crime and failing schools are sure-fire ways to drive the creative class out of the urban core.

It’s too early to declare that America’s great urban renaissance of the 21st century is spent. As Sablik notes, cities have shown great resilience throughout history in reinventing themselves. But not always. Some go into long-term decline. Which scenario do American cities face? That is one of the great questions of our age.