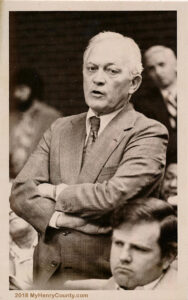

Jason Miyares, Attorney General of Virginia

by Dick Hall-Sizemore

Although the issue of school mask mandates is now behind us, it is instructive to examine the legal arguments advanced by Attorney General Jason Miyares in a court case seeking to overturn the mask mandates instituted by the Loudoun County School Board (“school board”). Not only does Miyares advocate judicial activism and misread statutory law, the breadth of the power he asserts for the governor is breathtaking.

At issue was whether the school board could continue to mandate the wearing of face masks by students despite the provisions of Governor Youngkin’s Executive Order No. Two (EO-2) that students are to have the option of wearing masks in school.

The state circuit courts have divided on this issue. The state Supreme Court dismissed, on technical grounds, a suit by Chesapeake parents challenging EO-2. A group of seven school boards filed suit in Arlington Circuit Court challenging the legality of EO-2. The court there issued a temporary injunction barring the enforcement of the mask-option policy set out in EO-2. The result was just the opposite in Loudoun. The court there issued a temporary injunction barring the mask mandate. Because there are no standards to guide Virginia courts in the issuance of temporary injunctions, it may be difficult to infer from that action how a court would ultimately rule. The order issued by the Loudoun County judge did not provide any specific grounds for granting the request for a temporary injunction other than “the reasons stated in the briefs, pleadings, and on the record at the…hearing.” The Washington Post reported that the judge said that the plaintiffs, consisting of parents and the Commonwealth, were likely to prevail in a trial. He was quoted as saying, “The executive order is a valid exercise of the governor of Virginia.”

Because no court has issued a ruling on the substance of the cases challenging the validity of EO-2, it cannot be said that the positions advanced by the Attorney General in the briefs filed in the defense of that order are the official, legal policy of the Commonwealth. Nevertheless, it is important to examine the briefs for insights into the philosophy of gubernatorial power put forth by the Attorney General and, by extension, the Governor.

First, the brief (the text of which can be found here) devotes a lot of pages arguing that the mask mandate is “ineffective and impractical.” It cites numerous studies to buttress its argument. Furthermore, it argues that masks are not necessary in schools because “COVID-19 infection and spread in schools is low,” and “the rate of hospitalization among school-age children is similarly low.” Regardless of the merits of those arguments, that is a policy decision for legislatures, not courts, to make. In the past, conservatives such as Miyares claims to be railed about “judicial activism” and complained that “courts should be interpreting, not making, law.”

The school board cited Chapter 456 of the 2021 Acts of Assembly (S.B. 1303) as its primary defense. That law requires school boards to offer in-person instruction to each child enrolled in its schools. It also required each school to:

provide such in-person instruction in a manner in which it adheres to the maximum extent practicable to any currently applicable mitigation strategies for early child care and education programs and elementary and secondary schools to reduce the transmission of COVID-19 that have been provided by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [emphasis added]

EO-2 acknowledges that “the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends masks,” as does the affidavit filed in the Loudoun circuit court by the Acting Commissioner of Health. However, Miyares’ brief contends, despite the Virginia statute requiring school boards to adhere to any “currently applicable mitigation strategies … that have been provided by” CDC, that the law “does not impose a universal mask mandate.” Miyares is asking the court to ignore the plain language of the statute.

Finally, and most importantly, there is the order itself. There are several ways of interpreting it, but the end results are either nonsense or very concerning as to the insight they provide into the vision that Miyares has of gubernatorial power and authority. Here is the beginning of the directive in EO-2:

Therefore, by virtue of the authority vested in me as Governor by Article V of the Constitution of Virginia, by § 44-146.17 of the Code of Virginia, by any other applicable law, and by virtue of the authority vested in the State Health Commissioner pursuant to §§ 32.1-13, 32.1-20, and 35.1-10 of the Code of Virginia, Executive Order Number Seventy-Nine (2021) is rescinded and the following is ordered:

1. The State Health Commissioner shall terminate Order of Public Health Emergency Order Ten (2021).

2. The parents of any child enrolled in a elementary or secondary school or a school based early childcare and educational program may elect for their children not to be subject to any mask mandate in effect at the child’s school or educational program….

A simple interpretation would be that the governor has rescinded the latest executive order and Order of Public Health Emergency regarding the emergency created by COVID-19 and ordered that school boards not require students to wear masks in school.

The governor certainly has the authority to rescind previous executive orders and public health emergency orders. But, by what authority does the governor get to issue an edict that schools cannot require students to wear masks, especially when state law gives school boards supervisory authority over schools and the 2021 legislation requires that masks be used by students? This is an edict that Miyares tells the court the school board has “disobeyed.” In this vein, can the governor issue edicts that all school children must wear uniforms, or that school boards cannot prevent a student from receiving a diploma even if he failed most of his classes, or that students cannot be required to do their homework assignments?

Recognizing that the Governor needed some sort of legislative authority to issue such an order, the authors of EO-2 cloaked him, paradoxically, in the protection of that law that conservatives now seem to hate: the Virginia Emergency Services and Disaster Law (VESDL), specifically Sec. 44-146.17 of the Code of Virginia. Accordingly, his order that schools not require students to wear masks was issued “by virtue vested in me as Governor…by Sec. 44-146.17 of the Code of Virginia.”

The VESDL defines “emergency” as “any occurrence, or threat thereof, whether natural or man-made, which results or may result in substantial injury or harm to the population or substantial damage to or loss of property or natural resources.” Section 44-146.17, cited in EO-2, authorizes the Governor to declare a state of emergency and to issue orders that “in his judgment, [are] necessary to accomplish the purposes of this chapter.” In Sec. 44-146.14, the General Assembly declared “generally to provide for the common defense and to protect the public peace, health, safety, and to preserve the lives and property and economic well-being of the Commonwealth, it is hereby found and declared to be necessary and to be the purpose of this chapter.”

With that established, one needs to ask, “What is the emergency that is the subject of EO-2?” Miyares’ brief states, “COVID-19 still poses a very real threat to public safety and continues to be an emergency under the VESDL” (p. 16, para. 63). If COVID-19 were really the emergency for which EO-2 was issued, it does not make any sense that the steps ordered by the Governor involved diminishing the use of a measure designed to reduce the transmission of the disease.

Actually, the purpose of EO-2, and the ostensible “emergency,” is stated explicitly in its title and first section: “reaffirming the rights of parents in the upbringing, education, and care of their children.” In the petition to the court to allow the Commonwealth to intervene in the case, Miyares declared, “The Governor has declared EO-2 is a necessary measure to protect public health, safety, and welfare during the COVID-19 emergency, in particular the health and safety of children.” In the next paragraph, he also asserts “The Governor has a duty to protect the rights of parents to guide the care and education of their children.” It is this latter objective that is emphasized throughout the briefs and in the executive order.

In EO-2, the Governor states, at the beginning, “Under Virginia law, parents, not the government, have the fundamental right to make decisions concerning the care of their children.” In his brief, Miyares declares that it was in light of this “fundamental right” that “Governor Youngkin invoked his VESDL power to rescind the previous order requiring all students to wear masks” and further ordered schools not to impose such mandates (p. 18, para. 67).

In summary, the “emergency” that caused the Governor to issue EO-2 was that, because their children were required to wear masks to school, the fundamental rights of some parents had been infringed upon and the Governor had a “duty” to protect those rights. Unaddressed are the fundamental rights of those parents who might feel that schools and the Governor have a duty to protect their children, to the extent possible, from the transmission of a deadly disease in schools.

Completely ignored in Miyares’ brief is the statutory definition of the type of emergency under which the Governor is authorized to exercise his extraordinary powers. It strains the borders of credibility to contend that schools requiring their children to wear masks with the intent to decrease the chances that they would transmit or catch a deadly disease infringes upon the rights of parents to the extent it “results or may result in substantial injury or harm … or substantial damage to or loss of property or natural resources.” It seems that, according to Miyares’ argument, an “emergency” is what the Governor says it is.

Before moving to discussing the implications of enabling a governor to use the VEDSL to manufacture an “emergency” for the purpose of unilaterally putting in place a campaign promise, it is worth exploring the concept of a parent’s right to make decisions regarding the care and education of their children.

First of all, the Governor expanded upon the law in his statement of it in EO-2. According to that document, “Under Virginia law, parents, not the government, have the fundamental right to make decisions concerning the care of their children.” However the text of the actual law is:

A parent has a fundamental right to make decisions concerning the upbringing, education, and care of the parent’s child.

There is no language in the statute excluding the role of the government. Furthermore, the statute says that a parent has “a” fundamental right, not “the fundamental right” asserted in the Governor’s rendition of the law. There is a difference. Using “the” lends a sense of exclusivity, ruling out the existence of any other entity having a right to make decisions about the case of a child.

Assuming that the statement of the law in EO-2 correctly reflects the administration and Miyares’ interpretation of the statute, consider the implications in the following scenarios:

- A parent refuses to have his child vaccinated against measles, as required by law, not due to religious convictions, but because the parent distrusts vaccinations.

- A parent refuses to send her child to school after age 14 on the grounds that schools are not that valuable after that age and the child can gain much more knowledge and valuable skills while working in the parent’s automobile repair shop, plumbing business, roofing company, etc.

- A parent disciplines his child with corporal punishment to the extent that the child frequently needs medical attention.

- A parent regularly leaves a six-year-old child at home alone as a way of teaching that child to be independent.

A.L. Philpott

This Code section is an example of the type of policy or philosophical statement that often appears at the beginning of a chapter in the Code. The late Delegate A.L. Philpott strongly objected to such statements and would order their removal from any legislation that came up in any committee upon which he sat. Long before he became Speaker, Philpott was regarded as the foremost authority on the Code of Virginia in the General Assembly, as well as in the Commonwealth. For Philpott, a statute or law should do one of three things: authorize something to be done, require something to be done, or prohibit something from being done. Philosophical or policy statements cannot be enforced and are subject to wide interpretation and, thus, have no place in a code of laws.

Jason Miyares never had the opportunity to serve in the House of Delegates with A.L. Philpott and experience his famous and feared scowl as he reviewed a bill. (It was said that Philpott’s scowl alone was enough to kill a bill.) Therefore, the foundation of his brief in the school mask mandate case is the wrongly stated statutory right of a parent, not the government, to make decisions about his child’s education.

Next, it is necessary to examine the implications of Miyares’ contention that the governor has the authority to declare an emergency when someone’s rights are being threatened. Under this interpretation, the “emergency” no longer is restricted to its commonly understood, and statutory, meaning. There no longer has to be a credible threat of people being physically injured or killed or of widespread property damage, such as in the case of a hurricane, tornado, flood, ice storm, or pandemic. An ”emergency” becomes something happening that a lot of people are upset about and feel their rights and interests are not being protected and the Governor “concludes that existing legal procedures fail to protect those rights and interests.”

Under the Miyares approach, the following scenarios would be plausible:

- The Governor declares the falling reading scores of minority students in some localities constitute an emergency and orders the school boards in those localities to approve the establishment of charter schools in their jurisdictions.

- The Governor declares the increase in the crime rate to be an emergency and orders that no prisoners currently incarcerated be released on parole, even if eligible for consideration for parole under the law.

Do conservatives really want a governor to have this sort of power? They may approve of the results set out above, but they need to keep in mind that such power could be wielded in ways in which they may not approve.

Here is an example of another possible use of the “Miyares doctrine.” The state constitution has the following declaration:

…it shall be the policy of the Commonwealth to conserve, develop, and utilize its natural resources, its public lands, and its historical sites and buildings. Further, it shall be the Commonwealth’s policy to protect its atmosphere, lands, and waters from pollution, impairment, or destruction, for the benefit, enjoyment, and general welfare of the people of the Commonwealth. (Article XI, Section 2)

Scenario: Under the provisions of the VESDL, the governor declares that climate change constitutes an emergency that threatens the Commonwealth and that, as Governor, he has a duty under the provisions of Article XI of the state constitution to protect the Commonwealth’s atmosphere from “impairment” for the “benefit of the people of the Commonwealth.” Accordingly, he orders a moratorium on all new residential, commercial, and industrial natural gas hookups. Also, he orders the suspension of all land-use regulations with regard to the siting and installation of solar panels.

The moral: Be careful of what you ask for. Once power is granted to a governor, it will be used by whatever governor is in office and maybe not for ends that you favor.