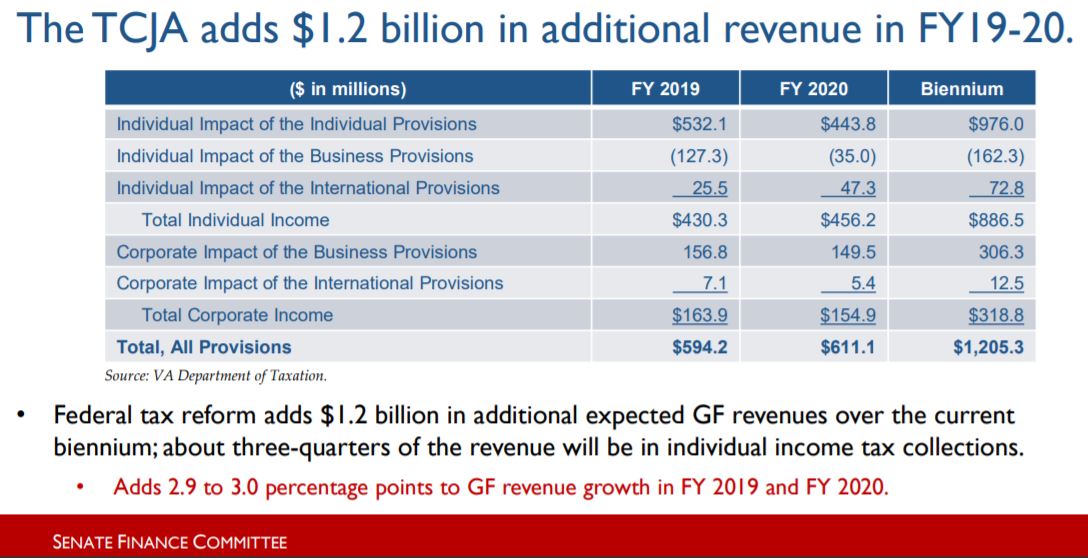

Senate Finance Committee data highlights the “conformity” tax impact on Virginia corporations. The Governor’s Office data lumps in all forms of businesses, implying a smaller impact on Virginia business. (Click for larger view.)

In proposals which would further distance Virginia from the tax reforms of President Donald Trump, the General Assembly is being asked to let Virginia corporations keep two major deductions no longer allowed at the federal level.

If the General Assembly agrees, the chance for a general corporate income tax rate reduction probably goes away. The protection of a well-connected few will outweigh a possible benefit to the many, which seems to be what always happens when Virginia tries tax reform.

The focus so far in the tax conformity debate has been on individual taxpayers, but $318 million of the $1.2 billion in new revenue generated by conformity over two years will come from corporations. You won’t find that number in any presentations from the Northam Administration, but the Senate Finance Committee reported it (see chart above.) In future years the new corporate income taxes grow faster than the individual taxes.

The focus so far in the tax conformity debate has been on individual taxpayers, but $318 million of the $1.2 billion in new revenue generated by conformity over two years will come from corporations. You won’t find that number in any presentations from the Northam Administration, but the Senate Finance Committee reported it (see chart above.) In future years the new corporate income taxes grow faster than the individual taxes.

It works the same as with individual taxes. Congress eliminated several popular deductions but compensated with major rate cuts, leaving lower taxes overall. If Virginia conforms to all the lost deductions but keeps its corporate tax rate the same, the result is higher taxes overall.

Many businesses don’t use either deduction, but some that do are pushing hard to maintain them at the state level.

There are several bills pending in the House and Senate that propose to reduce the state’s corporate income tax rate from 6 to 5 percent, in two half-percent steps. That step has been endorsed by the National Federation of Independent Business and the Virginia Manufacturers Association.

If the $300 million in expected corporate tax revenue growth is all you can work with, both steps cannot be taken at once. The 2019 General Assembly must either restore deductions o protect the select few or cut the rates to benefit all. (It also might do nothing on corporate taxes, and just spend the money.)

It is the same question as with the competing proposals dealing with individual taxes. Do you fully conform to the new federal system, but use the revenue to provide general tax relief through a higher standard deduction or lower rates? Or do you reject key parts of the new federal system and restore the status quo ante Trump.

The largest of the two deductions involved interest expenses, which are still deductible but now more limited under the new federal rules. Bills to restore the full interest deduction in Virginia include House Bill 2701 and Senate Bill 1697. According to the conformity revenue study commissioned by the Northam Administration, the new rules will cost certain Virginia taxpayers an additional $123 million for Tax Year 2018 and $90 million for Tax Year 2019.

That one conformity provision accounts for two-thirds of the additional revenue generated from corporations in 2018 and 2019.

The other issue has smaller dollars attached to it, about $7 million a year. Everybody enjoys the associated acronym, GILTI, which stands for Global Intangible Low-taxed Income. The bills to create a Virginia-only deduction for GILTI are House Bill 2700 and Senate Bill 1698. Virginia has long allowed a deduction for income earned overseas, so there is a strong argument that exempting this new category of taxable income is in line with that old policy.

Because there are individual bills, it is easy to adopt one and reject the other, which could happen. More details follow on the interest deduction, a.k.a. IRC Section 163(J).

As previously noted, Congress didn’t eliminate interest deductions for businesses but imposed major new limits. Those seeking to keep the full deduction on their state taxes argue it will make Virginia more attractive to investment and point to other examples where Virginia has refused to conform on business deductions.

“Congress only limited interest deductibility to pay for a lower federal corporate income tax rate and 100 percent expensing,” reads an industry handout supporting the deduction. “This way, companies are incentivized to invest in new assets without over-relying on debt. However, Virginia decouples from federal 100 percent expensing under IRC §168(k). Therefore, Virginia should decouple from IRC §163(j) because Congress intended for these provisions to act together.”

The sheet is being distributed by an organization known by the acronym OFII, made up of foreign-owned companies, which often do have complicated corporate structures and internal loans going back and forth across borders. Arguments over how to tax those structures and transactions have gone on as long as the U.S. has had an income tax.

Here is how the Department of Taxation described the issue in a recent presentation:

“Prior to TY 2018, the deduction of investment interest was limited. For individuals, the deduction is limited to investment income. For corporations, interest may be disallowed if debt-to-equity ratio exceeds 1.5/1.0 and net interest expense exceeds 50% of adjusted income. Disallowed interest may be carried forward.

“Beginning in 2018, the deduction is limited to 30% of the business’s adjusted income. Special rules or exemptions for partnerships, certain utilities, and businesses with gross receipts less than $25 million. Disallowed interest may be carried forward.”

It’s way more complicated than that. The actual IRS guidelines on the issue are long and illegible.

Easier to understand are two articles from Forbes magazine, here and here, which indicate Congress had policy reasons for what it did and was not just trying to grab revenue. For businesses or individuals, deductions nudge taxpayers toward a certain decision or investment. Congress was interested in reducing the incentives for corporate debt and creating a level playing field between debt and equity.

And it was going after the kind of behavior described in this Forbes excerpt:

“When you allow businesses to deduct interest expense, big businesses will abuse that deduction. A primary example is so-called “earnings strippings,” where a U.S. corporation borrows money from a foreign affiliate in a low-tax jurisdiction. When the U.S. (affiliate) deducts the interest it pays on the borrowing, it “strips” the earnings out of the (pre-2018) high-tax U.S., and moves those earnings to a lower-tax or tax-indifferent locale.”