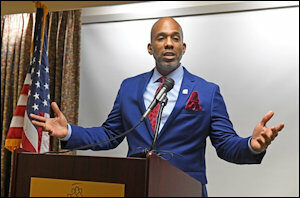

The Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority has a new chief executive, Damon Duncan, who led a housing authority in the Chicago suburbs before taking on his new role in March. He has a tough job. The public housing stock has been deteriorating — units have outlived their useful life by 10 to 15 years at least, he says. And Richmond housing projects are beset by crime, much of it committed by outsiders. Between the maintenance backlogs and the high crime rates, public housing in Richmond is a scandal.

In a Style Weekly profile, Duncan comes across as energetic and willing to challenge the status quo. What impresses me most is that he’s talking about making changes that will surely ruffle feathers in the poverty-industrial complex. To receive subsidized housing, he says, residents will have to work or enroll in education or training programs. Writes Style:

“One thing we didn’t talk about, but we’ll talk about at a later time, is the level of accountability that we’re expecting from the residents in the way of participation with human services programs,” Duncan says, explaining that the agency will move toward requiring able-bodied heads of households to work or enroll in education or training programs to receive public housing assistance or Section 8 vouchers.

“There are some things that we’re going to start to make policy that may be controversial with some of the advocates and some of the other folks,” he says. “But I believe, having worked on the supportive side and the development side, that a lot of these forces help to keep conditions the same.”

This is an interesting development. A less incurious media might ask some follow-up questions:

- What exactly are the work/education/training requirements for able-bodied heads of household?

- How scrupulously have those requirements been enforced?

- How many able-bodied adults are benefiting from subsidized rents, and what percentage is participating in the workforce programs?

- Do the programs work? How many participants eventually find work that allow them to move out of the projects?

Put another way, do Richmond’s public housing programs promote upward social mobility or do they create a poverty trap?

The other question I’d really like to see Duncan address is this: Why does it cost $200,000 per apartment unit in the Richmond region to build affordable housing? In Richmond, the housing authority already owns the land, so that’s a freebie. What makes re-development so incredibly expensive? Is it federal regulations? State and local regulations? Minimum square-footage requirements? Mind-numbing bureaucracy and administrative overhead? Greedy private-sector developers? All of the above? Getting answers would seem fundamental to any rational discussion of how best to provide decent housing for the poor.