Citing housing affordability as the key issue, the Virginia Board of Housing and Community Development has voted down an update to the state building code that would have mandated the installation of sprinklers in all new single-family homes and townhouses.

Virginia home builders have said that the sprinkler requirement would add between $15,000 and $25,000 to the construction cost of a new residence, according to reporting by WAMU, American University Radio. Keith Brower, a former Loudoun County fire chief has countered that the cost would be significantly less, about $5,000 for a 2,000-square-foot house. Whatever the case, there is no debate that the mandate would have added thousands of dollars to the cost of a dwelling unit.

WAMU summarized the home builders’ arguments this way:

Home-builders hailed the 10-4 vote taken Monday, saying that requiring sprinklers would only throw another obstacle in the way of the new housing construction that is needed to help close what officials say is a 75,000-home gap between what’s currently expected to be built across the region and what’s actually needed to keep pace with estimated job growth.

“We’re seeing that in Northern Virginia, we’re seeing it across the state that localities are really struggling to find ways to create to create mixed-income communities, to provide housing for folks at all income levels,” says Andrew Clark, the vice-president of government affairs for the Home Builders Association of Virginia. “And keep in mind that code proposals can have an impact on affordable housing and the ability to provide a diversity of housing stock in our communities.”

Housing affordability is a social crisis, especially in Northern Virginia. Affordable housing is not a concern of Virginia fire fighters — fighting fires is. But Brower’s concerns cannot be dismissed lightly:

“We used to say you have 10 to 13 minutes to get out of your house, and that was because you had a lot of natural fabrics in your furnishings. Over the last 15 or 20 years, everything is now synthetic. Everything in your home is now a highly volatile, combustible product. What we’re finding now is that fire spread has increased so rapidly that people only have two to three minutes to get out,” he says. “The sprinklers are designed to give people time to get out.”

So, we have a battle of dueling crises — unaffordable housing vs. flammable housing. Which is of a greater magnitude when it comes to public health and welfare, and which consideration should prevail?

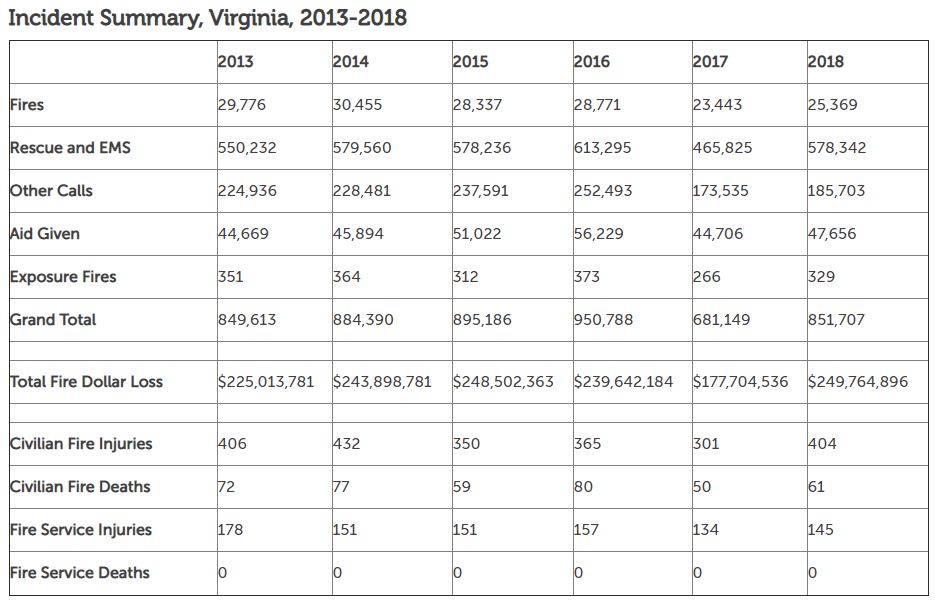

Here is the number of fires, injuries and fatalities in Virginia:

Last year there were 61 fire-related fatalities, 404 fire-related injuries, and $250 million of fire-related property damages in Virginia. With random blips up and down each year, the numbers have been fairly stable since 2013.

That gives us an idea of the magnitude of the threat posed by house fires. What it doesn’t tell us is what impact the mandatory installation of sprinklers will have on the numbers. Given the fact that changes to the building code would not mandate retrofits to the existing housing stock, however, the answer is probably Not Much. It will take years and decades to see the benefits of mandatory sprinklers as new housing stock replaces new housing stock.

By contrast, insofar as the price of newly built housing sets a benchmark for the price of existing housing, changes to the building code have an ripple effect across the entire housing stock, immediately impacting everyone seeking to rent or buy a new house.

Higher rents and mortgages diminish income that households can spend on other priorities — such as health and safety. Households will spend some percentage of their income on safer cars, better health care or, who knows, voluntarily installing sprinklers.

It’s hard to measure the effect, however, so let’s focus on the most vulnerable population, the homeless. As of 2018, the homeless population of Virginia numbered 5,975, according to the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. Many people are homeless due to alcohol and drug addiction, so their plight may seem only tangentially related to the cost of housing. But the estimated 660 homeless families are a different matter; most are homeless because they have been effectively priced out of the market housing and evicted because of an inability to pay rent. As housing prices continue to rise, so will the number of homeless families.

The question then becomes, what are the health and safety effects of homelessness? “Research … indicates that individuals experiencing homelessness have a risk of mortality that is 1.5 to 11.5 times greater than the risk in the general population,” states a 2017 paper by the American Public Health Association. Clearly, there is a relationship.

The data I present here is spotty and inconclusive, but, hopefully, I have illuminated a useful way of examining the public health and safety trade-offs between making housing more affordable and making it more safe. I strongly incline toward a conclusion that the Virginia Board of Housing and Community Development made the right decision, but I’m open to seeing more data and other ways of analyzing the issue.