The Washington Post takes note today of three bills affecting Virginia’s sovereign Indian tribes moving through the General Assembly. One would update state code to reflect federal recognition of the tribes. One would make tribes eligible for grants from the Virginia Land Conservation Fund. And third would give federally recognized tribes, in the WaPo’s words, “a voice” in the permitting process for development projects affecting their ancestral lands. After clearing the state Senate 40 to 0, the legislation was blocked by a subcommittee in the House of Delegates.

Last year former Governor Ralph Northam issued an executive order requiring state agencies to notify Virginia’s seven federally recognized tribes of projects affecting their lands. State Bill 482 represents an effort to codify the order, which subsequent governors could reverse, in state law.

The logic of Republicans in blocking the measure was less than clear. The WaPo article quotes Delegate Lee Ware, R-Powhatan, as saying “It has the potential, in my judgment, to have a very wide-ranging … effect with a variety of permitting processes with state agencies.”

That’s not much of an explanation, but I expect there was more to Ware’s thinking than made it into the WaPo article. More important than the bureaucratic procedure it proposes to address, the bill raises the issue of what citizenship means for American Indians.

SB 482 called for creating a Tribal Consultation ombudsman to “facilitate communication” with federally recognized Tribal Nations on environmental, cultural, and historical reviews and permits, and require the Department of Environmental Quality to consult with the Tribal Nations regarding permitting policies and procedures. States the bill:

The policy shall define an appropriate means of notifying federally recognized Tribal Nations in the Commonwealth based on tribal preferences, ensure that sufficient information and time is provided for the Tribal Nations to develop informed opinions about the proposed action, and establish procedures for the Department to provide feedback to the Tribal Nations to explain how their input was considered.

It’s hard to get exercised one way or another about notifying tribal authorities of a project — a pipeline, say, or an electric transmission line — that might affect them. The permitting process is so lengthy and the requirements for public notification so extensive that tribal leaders already get a heads-up by availing themselves of the rights due to all American citizens.

But the bill adds yet another procedural step to a ponderous process, and creates another tool for gumming up bureaucratic reviews, which, I conjecture, is Ware’s concern. Environmentalist groups have perfected the art of utilizing lawfare to defeat infrastructure projects by dragging out the permitting approvals endlessly. A rule requiring notification of the Indian tribes — as tribal entities, not indigenous Americans as private citizens — adds one more potential hurdle.

But there’s an even bigger question. As the WaPo wrote in a previous article, Northam’s executive order represented an important step in the tribes’ fight for self-determination.

“This executive order is a historic step forward in advancing the government-to-government relationship between Tribal Nations and states in this country,” Fawn Sharp, president of the National Congress of American Indians, said in a statement. She said the order honors “the inherent right to free, prior, and informed consent,” an international human rights principle. …

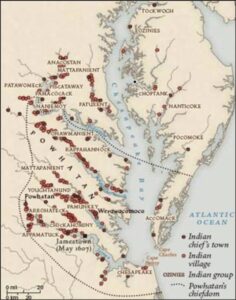

“This order helps advance the relationship between the Commonwealth and our tribes, after the United States recognized our sovereignty in 2018, and it affirms the Commonwealth’s obligations under treaties stretching back more than 300 years,” [G. Anne Richard, chief of the Rappahannock tribe] said in a statement.

Yeah, I know we’re supposed to feel guilty for the sins committed by our ancestors against the ancestors of modern-day Indians. (More about that in another column.) Sorry, but the Indians lost their bid to maintain their independence. Guess what, the Mormons settling Utah lost their bid to maintain their independence, too. So did the Southern states that seceded from the union in 1860. That’s the way it goes. Get over it. Why isn’t it sufficient to say that native Americans are as American as everyone else, and they’re entitled to the full rights of all American citizens — but no more?