by James A. Bacon

Instead of getting all torqued up about becoming Second Amendment sanctuary cities, suggests a Roanoke Times editorial, citizens of rural Virginia counties should be mobilizing to demand more funding for local school systems.

Arlington County spends $20,460 per student, notes the editorial. The City of Norton spends only $9,219. While the editorial writer concedes in passing that “throwing money at the problem” may not be the best answer, he or she insists that money can fix leaking roofs or buy new technology.

“While you’re all fired up with civic activism,” the editorial admonishes, “start passing some resolutions in favor of more school funding. Unless, of course, guns really are all you care about.”

Ah, so much conventional thinking packed into so little space. Where do I begin?

The editorial assumes that there is a strong correlation between the spending per student and the quality of the education received. Since the editorial compared Arlington County and the City of Norton, let’s take a look at the numbers for those two school systems.

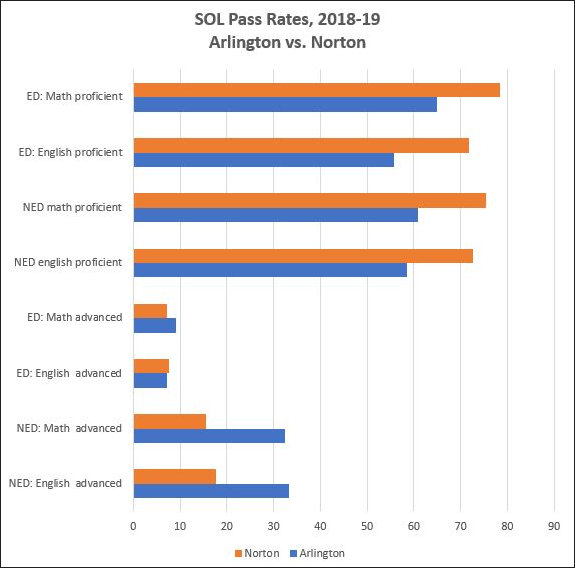

In the graph above, I show Standards of Learning (SOL) “proficient” and “advanced” pass rates for English and Math for both school systems in the 2018-19 school year. Further, I break down the pass rates for Economically Disadvantaged students and Non Economically Disadvantaged students.

When it came to passing the SOLs at a “proficient” level, which might better be described as the “adequate” level, Norton out-performed Arlington across the board — in English and math, for economically disadvantaged students and non disadvantaged. Norton’s school system endeavors to ensure that all kids achieve a basic mastery of subject matter and, despite spending half the money per student, it did a better job of it than Arlington.

How about the “advanced” pass rate? Arlington and Norton performed comparably for economically disadvantaged students, while Arlington shined in educating non-disadvantaged students. It is possible that Arlington does, in fact, do a better job of educating its affluent students. However, I would not accept that conclusion without closer examination.

The category of “non economically disadvantaged” encompasses a wide socioeconomic range, including better-off blue collar workers, the middle class, and the professional class.In 2017, the median household income in Arlington was $112,138. In Norton, it was $16,024. The percentage of Arlington adults with a four-year college degree or higher level of education was 74.1%. In Norton, it was 17%. It is safe to say that Arlington’s student population is skewed to the professional end of the spectrum, while Norton is skewed toward the working/middle class end of the spectrum.

It is widely accepted that, all other factors being equal, students from affluent, well-educated families academically out-perform students from less affluent, less-educated families on average.

While it is true that the better-off Arlington students passed their SOLs at an “advanced” level at roughly double the rate of their better-off counterparts in Norton, one must consider that we are comparing the children of lawyers, PhDs, and MBAs from elite institutions to the children of high school, junior college, and regional college graduates. In other words, what we’re likely seeing in Arlington’s superior “advanced” pass rate could be the vast demographic disparity, not the quality of education provided.

To be sure, if Arlington County can afford to fund a sport as arcane as high school crew, it undoubtedly provides advanced and specialized courses that are unavailable to high school students in Norton. If I had the ambition to go to an Ivy League college, I’d rather attend public high school in Arlington than Norton. But, getting back to the Roanoke Times editorial, I reject the premise that insufficient funding is a first-order problem for Norton and other rural/small town communities in Virginia where very few students burn with a desire to attend Harvard or Yale.

To the contrary, schools in Southwest Virginia out-perform schools in other regions in Virginia by banding together in the Comprehensive Instructional Program to share best practices. Necessity, to borrow a phrase, can be the mother of innovation that brings about more meaningful change than mo’ money could.

Bacon’s bottom line: As I’ve opined before, I don’t have any more sympathy for Second Amendment sanctuaries than I do for illegal-immigrant sanctuaries. The idea that localities can pick and choose the laws they enforce is a pernicious one. So, I suppose I agree with the Roanoke Times that the residents of Virginia’s rural counties could find better things to get agitated about. But pouring mo’ money into local schools won’t address a pressing need. Rather, rural/small town citizens should get charged up about the opioid epidemic, physician shortages, the lack of broadband access, the paucity of employment opportunities — areas where deficiencies directly impact their quality of life.