In the last post I pledged to explore, and hopefully to explain, the social epidemic of broken kids. For all our rising incomes and for all our advances in health care, the number of children suffering from physical, emotional, and sexual abuse as well as the number diagnosed with autism, ADHD, anxiety, depression, and other cognitive and emotional disorders appears to be on the rise. The problem cannot be attributed to one single cause. It is multi-factorial and complex.

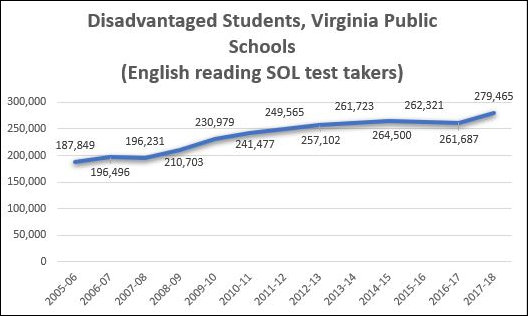

I’m certainly no expert, just a journalist trying to understand what’s happening. One place to start is to look at numbers generated by the Virginia Department of Education and made accessible through its searchable Build-a-Table database of Standards of Learning test takers. VDOE tracks the number of kids designated disadvantaged (eligible for free school lunch programs), disabled (falling within one of 10 sub-classifications), and homeless. All are associated with higher failure rates in SOL tests, and all are associated with behavioral problems that disrupt classes for other children.

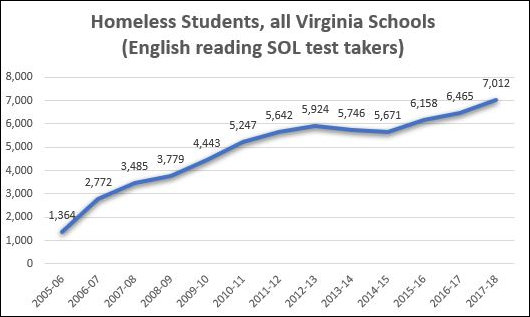

In absolute terms, the number of homeless children is not huge (although certainly way higher than one would hope for) — 7,000 in the 2017-18 school year. But the increase is alarming — the number has quadrupled over the 12 years for which VDOE has data.

Homeless children no doubt come from a wide variety of circumstances. The parents of some may be just down on their luck. Other parents may be drug addicts or alcoholics, or rotating in and out of jail. Many have bounced back and forth between homeless shelters, the homes of family members, and their own apartments. The lives of most are disordered if not downright chaotic. There is a good chance they experience physical and emotional abuse or neglect in ways that effect their learning and social behavior.

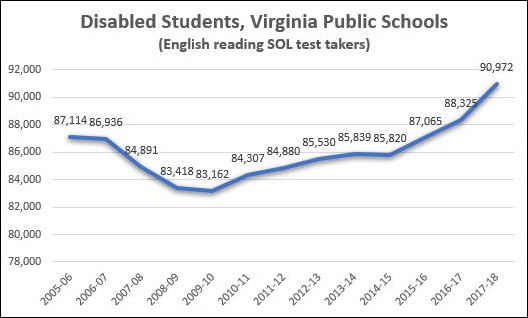

The population of children with disabilities is far larger — more than 90,000 last year. In a previous post, I had noted that the increase over the 12-year period did not seem calamitous, only 4%. But I did not look closely enough at the data. The period between 2005-06 and 2009-10 showed a decline in the number of children with disabilities. I have no explanation for that decline, and it seems to fly in the face of all other evidence, so I suspect it may be a statistical artifact of how the data was collected or reported. If we look at the period of 2009-10 to 2017-18, we see an increase of 9.4%.

The big drivers of the disability numbers in recent years appear to be autism and ADHD, causes are not well understood but appear to be medical in origin, not tied to social conditions. It’s not clear how much those disorders have increased versus how many children have been reclassified from one disability to another. Regardless, under our current legal structure which mandates that children be placed in the least restrictive environment possible, many of these children are being mainstreamed with implications for public school budgets and the maintenance of classroom discipline.

Meanwhile, despite a growing economy since 2008 and a declining jobless rate, the number of disadvantaged students has increased relentlessly as well. Many of these children come from broken homes with single mothers and are more likely to be exposed to the pathologies of America’s poverty sub-culture. Not only do they get less support at home for their schooling, they are more likely to endure physical and emotional abuse and neglect and, therefore, overlap to a significant degree with the kids with disabilities.

With the number of disadvantaged, disabled, and homeless kids all on the rise, Virginia’s public schools face unprecedented challenges. I have been highly critical of the public schools in the past, and I acknowledge that I have not been fully appreciative of how difficult their task is. We are facing a societal crisis, an epidemic of broken children arising in part from spreading social dysfunction and in part from medical causes we don’t fully understand, and these social and medical problems are being dumped onto the schools.

I’m still skeptical of the shift toward a disciplinary system based on the principles of restorative justice. I’m still suspicious that school officials are covering up the dysfunction by gaming numbers. I’m still not convinced that “mo’ money” is always the answer. But there seems no denying that schools are caught between a budgetary rock and a hard place of needy children. Society no longer looks to schools merely to educate but to address problems that originated elsewhere.