by James A. Bacon

For many social justice activists — please note, I refrain from using the potentially inflammatory term social justice “warriors” — racial disparities in the United States are a fixation. They have made an issue of the fact that African-Americans are more likely than whites to contract the COVID-19 virus than whites, which supports their contention that the U.S. health care system is unjust, and inequities can be remedied only through government action.

Maybe the system is unjust, maybe it isn’t. If it is, we can argue over the reasons why that might be so despite the transfer of hundreds of billions of dollars from taxpayers and privately insured patients to the poor. But before we jump to conclusions, let’s look at the numbers.

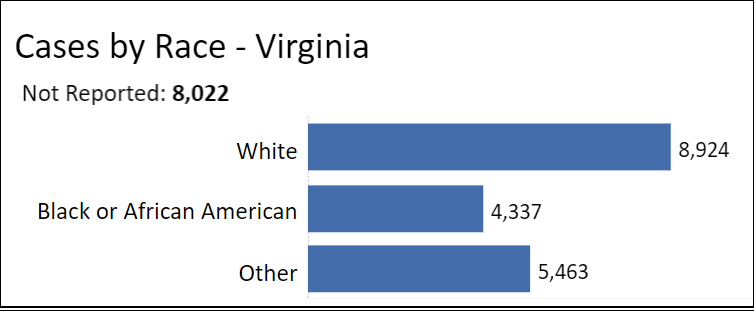

As can be seen in from the graph above, among Virginian patients whose race has been reported, African-Americans account for 4,337 cases, or 23.2% of all cases. That is slightly larger than African-Americans’ 19% share of Virginia’s population. By contrast, whites, who comprise 68% of the population, account for only 8,924, or 48%, of COVID-19 patients. That is what the SJAs (social justice activists) call a “disparity.” To the SJA way of thinking, disparities constitute proof — no further evidence needed — of injustice.

The first question we might ask is why blacks are more likely than whites to contract the disease. Does this disparity reflect inequities in the health care system or some other explanatory factor?

Commenting on CNN, basketball legend Magic Johnson drew a parallel between the HIV epidemic and the COVID-19 epidemic. “When I announced [that I had HIV], it was considered a white, gay man’s disease. People were wrong. Blacks people didn’t think they could get HIV and AIDS.” The implication of his remark is that African-Americans did not immediately take COVID-19 as seriously as they should have.

Other possible factors, suggested Johnson, were the higher prevalence of underlying health conditions such as obesity, diabetes and high blood pressure; the high cost of health care; and the the fact that a higher percentage of African-Americans work in “essential services” occupations where they are more likely to be exposed to the virus. He also said it was more difficult for African-Americans living in inner cites to get test kits. “The problem is people want us to drive to suburban American to get that test. Why can’t you have that testing done right in urban America and right in the inner cities?”

Johnson provides several worthy hypotheses of why COVID-19 has affected African-Americans to a greater extent than whites. They warrant a closer look. But before we draw any conclusions, let us dig a little deeper into the Virginia data. This graph shows hospitalization by race.

African-Americans comprise 858, or 26.7%, of all COVID-19 hospitalizations in Virginia among those whom race is known. That’s higher than the 23.2% who contract the disease. That implies that African-Americans are somewhat more likely to contract severe cases requiring medical attention. This is consistent with Johnson’s argument that African-Americans are more likely than whites to suffer from underlying health conditions that aggravate the disease. It is not consistent with the notion that African-Americans lack access to the health care system. Indeed, it appears that African-American COVID-19 patients make greater utilization of hospitals than whites with COVID-19.

A retort of social justice activists might be that the higher prevalence among non-Hispanic blacks of co-existing conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension reflect differential access to primary health care, ergo it constitutes a social injustice. I won’t argue that point one way or the other at this time. Either way, we need to distinguish between access to primary health care and access to acute care treatment, or hospitalization.

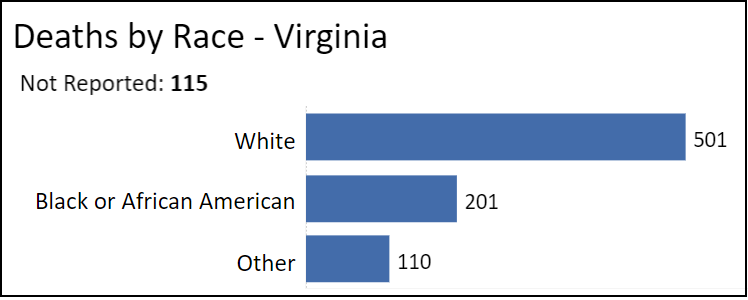

Finally, let us look at deaths by race.

African-Americans account for 201, or 24.8% of all COVID-related deaths — somewhat higher than their percentage of Virginia’s population but lower than their percentage of hospitalizations. (Conversely, the death rate for whites shoots up to 62%.) If African-Americans die at lower rates than they are hospitalized, it suggests that the quality of care they receive in hospitals is as good as the care received by whites.

Bacon’s bottom line: Any analysis quickly gets complicated. The limited data we have suggests that the greatest problems for African-Americans stems from the travails of lower socio-economic status: higher prevalence of pre-existing conditions, greater involvement in service occupations exposed to the public, living in over-crowded housing, and, one might add, greater use of mass transit. Personal behavior — the willingness to take protective precautions — is a factor that simply hasn’t been examined carefully. Access to protective gear such as masks, plastic gloves, and hand cleanser — a matter of access to cash — could be a factor. What does not appear to be a factor is access to hospitals and the quality of treatment in hospitals once the disease has progressed to the acute phase.

When it comes to addressing a public health emergency like COVID-19, it helps no one to impose a rigid ideological framework on the data in order to confirm pre-existing suppositions. The more factors we consider, even if some are politically incorrect, the better our analysis will be. Flawed diagnoses leads to flawed treatments. Well-grounded diagnoses leads to better treatments — whether we’re dealing with social issues or epidemics.