by James A. Bacon

Court-imposed fines and fees set poverty traps, disproportionately burden black communities, and “affront basic notions of equal protection under the law,” asserts The Commonwealth Institute (CI), a center-left think tank, in a new report, “Set Up to Fail.”

Fines and fees relating to traffic and criminal cases amount to less than $200 million in fiscal 2019, a modest sum in the context of Virginia’s $70 billion budget, says the report, but they lock people into cycles of debt they cannot escape. “Unpaid court debt, even when resulting from low-level offenses, often leads to additional costs, court hearings, wage garnishments, and even deductions from state tax refunds.”

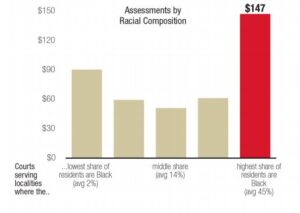

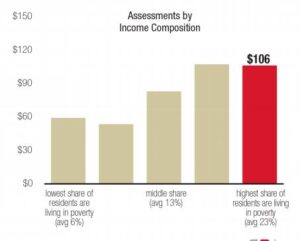

The use of fines and fees does not afflict all poor Virginians equally, contends the Institute. “Race — explicitly or implicitly — is a factor that influences the level at which fines and fees are imposed. … Fines and fees are imposed at the highest rates in areas with the largest percentages of Black Virginians.”

I think it is fair to say that CI has highlighted a real social problem. Poor people in Virginia do get caught in cycles of fines, fees, unpaid debt, compounding interest, and second-round punishments and fees stemming from the first. In a related problem, not related in this report, courts often take away peoples’ driving licenses as punishment for their inability to repay the fines, thus hindering their ability to generate an income. But is race really a factor? CI’s case is much weaker.

My sense is that the system of judicial fines and fees does need reform, and CI offers some good ideas of how to fix it. But it seems that highlighting government policies that merely afflict the poor doesn’t provide enough traction these days. You can turb0-charge your case by arguing the policies are racist by showing a disproportionate impact on African Americans — even if what you’re really showing is that African Americans are disproportionately poor, not that the rules are applied unfairly.

That said, CI makes raises some valid issues.

Fines and fees can quickly mount, especially for people lacking the means to pay them quickly.

A $30 fine for an improper U-turn, for example, can balloon into a nearly $220 debt, especially for Virginians who cannot afford to pay upfront and must rely on payment plans, or who write a bad check during the payment process, or who — perhaps because of work conflicts or family obligations — miss a court date.

While courts have discretion to reduce and even waive court debt, this is only permitted by the statute after someone has defaulted on their payments and following additional court hearings. In other words, relief only comes at the bitter end, when someone fails to pay despite good faith efforts to do so — even then, relief is not guaranteed.

Adding insult to injury, CI argues that fines and fees are an inefficient source of raising revenue. Much of what courts assess is never collected. Over the last five years for which data is available, courts levied $2.3 billion in assessments but collected only $1.4 billion. States the report: “Year after year, Virginia squanders resources chasing after uncollectable court debt and imposing fines and fees at levels that lock people into cycles of debt they cannot escape.”

The CI analysis becomes more problematic when it addresses the issue of race. “Our regression model controlled for factors such as population size and poverty rates to show how race — as opposed to other possible factors — influences fines and fees. In the end, the results were clear: as the Black population share increases, fines and fees assessments per capita also rises.”

Think through the implications of this. In effect, CI is saying that judicial practices are most racist in localities with the highest percentage of black residents — in cities such as Richmond, Petersburg, Portsmouth, and Newport News where blacks have strong representation on city councils, dominate key government positions, and, whose representatives in the General Assembly have a strong say-so in the appointment of judges within their localities. Does that sound plausible? Surely not.

Here’s another theory: blacks suffer a disproportionate share of fines and fees because they have a disproportionate share of encounters with criminal and traffic courts. I suppose that some would argue that the criminal laws are racist — especially those criminalizing marijuana possession — but CI does not make that case. And it is hard to see how traffic laws are racist, unless it’s racist to charge people for reckless driving, driving without a license or failure to purchase decals.

Indeed, CI backhandedly concedes the weakness of its case. One of its recommendations is to expand data collection to “understand racial disparities.” Publishing data on the assessment and collection of fines and fees by race and ethnicity “will help policymakers understand and address the disproportionate harm to Black communities.” If the argument were cut-and-dried, there would be no need for such data collection.

But there seems no disputing that fines and fees create a real hardship for poor Virginians, of whatever race or ethnicity. CI’s recommendations to “eliminate poverty penalties” sound reasonable. Rather than proposing to abolish fines and fees — a utopian idea — CI targets the most onerous aspects.

- Repeal the $10 “time to pay” fee for people who need more than 90 days to pay their court debt.

- Eliminate mandatory down payments, which can exceed $50 and create barriers to participate in court repayment plans.

- Ensure that interest that accrues on court debt when an individual is incarcerated is automatically waived, without the necessity of navigating a burdensome process.

- Make it easier for people to repay their debts through community service.

Public policy in Virginia should be aimed at fighting poverty and promoting upward social mobility. There is no need to create a sense of artificial urgency by describing the system as racist. We know it creates poverty traps for poor people, and that should be justification enough.