Solar energy is widely regarded as the most cost-effective source of electricity available today. According to financial advisory firm Lazard, the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) for solar, about $30 per MWh, is nearly half that of the most cost-effective fossil fuel, combined-cycle natural gas. The great economic advantage of solar, of course, is that is has no fuel cost. The sun is free.

Now an article in the Harvard Business Review, “The Dark Side of Solar Power,” suggests that the LCOE for solar could be four times greater when the full life-cycle cost, including recycling, is taken into account.

The problem is that solar panels contain small quantities of potentially toxic chemicals, primarily cadmium and lead. These are the very same heavy metals that caused massive freak-outs when they were found in the coal-ash waste of power plant ponds. Worried that leachate from coal ash could contaminate the water supply, environmentalists insisted that the material had to be buried in double-lined landfills at the cost of billions of dollars.

There is widespread agreement that the solar panels must be recycled. But the volume of the task will be far greater than anticipated, and the industry is totally unprepared, say the HBR authors, Atalay Atasu, Serasu Duran, and Luk N. Van Wassenhove.

Solar energy is a large component of Virginia’s electric-power mix, and it will grow significantly as the state’s electric utilities press toward the goal of a net-zero carbon electric grid by 2050. The recycling issue is unavoidable here. But there is no indication that Virginia is remotely prepared for coming crunch.

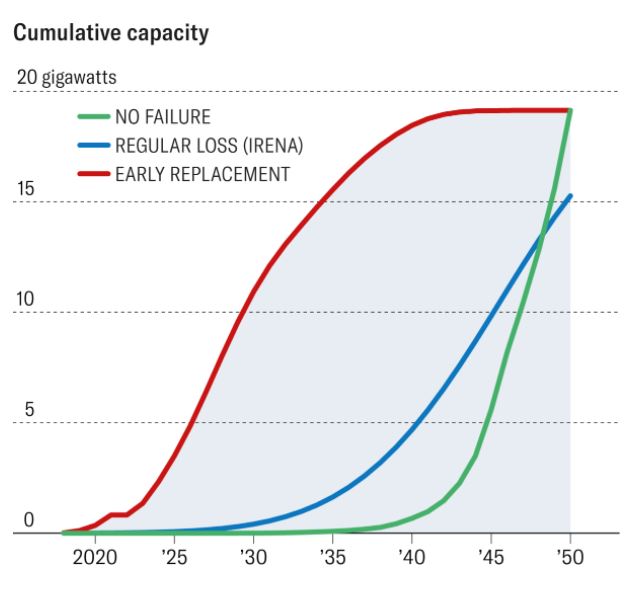

The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) projects that solar-panel recycling waste could total 78 million tons by 2050. That sounds like a lot, but thirty years does give us three decades to prepare. However, Atasu and his co-authors don’t believe that estimate is remotely realistic. Recycling volumes will be much higher, and the crunch will come much sooner. Ironically, one factor driving the crunch is the steadily improving productivity of the solar panels. Instead of using solar panels for their full expected life of 30 years or so, the authors say it will make financial sense for solar enthusiasts to replace them earlier to take advantage of the greater efficiencies. The result: More solar panels will need recycling.

This graph, taken from the FBR article, shows three projections. The green line charts the recycling volume if all solar panels last 30 years. The blue line shows the IRENA forecast, which allows for some replacements early in the life cycle. And the red line displays the authors’ predictions.

“If early replacements occur as predicted by our statistical model, they can produce 50 times more waste in just four years than IRENA anticipates,” they write. Add commercial and industrial panels, and the scale of replacements could be much larger.

By 2035, discarded panels would outweigh new units sold by 2.56 times. In turn, this would catapult the LCOE (levelized cost of energy, a measure of the overall cost of an energy-producing asset over its lifetime) to four times the current projection. The economics of solar — so bright-seeming from the vantage point of 2021 — would darken quickly as the industry sinks under the weight of its own trash.

A big question is who will bear the cleanup costs. The U.S. might follow the European’s WEEE Directive, apportioning recycling responsibility to manufacturers based on market share. The trouble with that is accounting for “orphan waste,” waste generated by companies that are no longer in business. Adding to the risk, the biggest manufacturers are Chinese. What happens if the Chinese government cuts its subsidies and producers fall out of the market? Who will take up the slack, and at what cost?

A similar problem looms for the wind industry — 720,000 tons of wind turbine blades could fill U.S. landfills over the next 20 years — and electric battery makers, the authors say.

Devising legislative remedies and building the infrastructure to handle this volume of “green” waste could take years, warn the authors, who, by the way, fully support the shift from fossil fuels to renewable fuels. If their analysis is sound, we need to get started now.

Bacon’s bottom line: If past is prelude, Virginia politicians won’t get around to dealing with the recycling issue until it becomes a crisis, and then the cost of dealing with it will be so much higher.

I do have one question about the article. The authors say that at current recycling capacity, it costs First Solar, the sole U.S. panel manufacturer with an up-and-running recycling program, $20 to $30 to recycle one solar panel. By contrast, it costs $1 to $2 to put it in a landfill.

Well, why not put the solar panels in a landfill? What is the obsession with recycling? The authors never address that question.

Whatever route is taken, it makes sense for Virginia to start working on the issue now, it makes sense to ensure that solar energy encompasses its full life-cycle costs, and it makes sense to ponder the implications for solar power in the Old Dominion.