by Reed Fawell III

This is the second of five posts on the events surrounding the white nationalist protests against efforts to remove the Lee and Jackson statues that occurred in the spring and summer of 2017 in Charlottesville, Va. The facts asserted are based on the narrative found in the “Independent Review of the 2017 Protest Event in Charlottesville.”

An altogether different cast of white nationalists, a Ku Klux Klan group based in Pelham, N.C., decided to protest Charlottesville’s decision to remove the Lee statue soon after the news of the May 13 rallies reached them. On May 24, 2017, a Klan member (the Klan Rep.) filed an application for a “public demonstration” on July 8, from 3:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. to “stop cultural genocide” in Charlottesville.

Based on her experience at such rallies held in Berkeley, Ca.; Danville, Va.; Columbia, SC; Raleigh, NC; and Stuart, Va., the Klan Rep. requested that Charlottesville:

- provide bus transport for the Klan from a secret offsite location to and from the protest site in Charlottesville, given that “jurisdictions that use this strategy keep the Klan separated from protesters,” and that,

- the city delay announcing the Klan event to the public “until the last minute.’ Again, in her experience, a delay in announcing Klan events until the last minute would result in a smaller and less hostile crowd of counter-protesters at the event.

The city declined both requests. It publicized the rally on May 24, the day the Klan filed its application. It later also denied bus transport, believing buses unnecessary. The Charlottesville Police Department (CPD) did agree with the Klan as follows.

The rally event would be shifted from the Charlottesville City Circuit Courthouse steps, as originally requested by the Klan, to the site of the Jackson statue in Justice Park that had just been renamed from Jackson Park, its original name since 1921.

Regarding transport, the CPD would meet the Klan at “a secret location on City property just outside the downtown area.” From that rendezvous point, two CPD squad cars would escort the Klan’s caravan of cars (not to exceed 25) to a surface parking lot in the city next to the Albemarle County Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court (JDR). This lot was within a short walking distance across Park Street to the Klan’s designated rally area (KKK Zone) within Justice Park. Once parked on the surface lot, the police would escort the Klan on foot to their KKK Zone.

To facilitate this plan, the Klan would assemble overnight in Waynesboro, Va, then drive over the mountain to Charlottesville the next afternoon. In so doing, the Klan would alert CPD to its arrival when 10 minutes away from the rendezvous site to assure their timely arrival at Justice Park by 3:00 p.m.

The CPD later described the Klan Rep as “overall, very cooperative” in working out their plan. CPD also said that the Klan ‘adhered to the plan’ created by the police.

The Klan’s Rep., however, expressed grave concerns soon after she learned that the City had announced their rally to the public on June 24. She told CPD that the “counter-protesters had begun organizing on social media to attend the Klan event while armed, and she urged a weapons check at Justice Park to avoid a ‘blood bath.’”

These, and subsequent events, would highlight Charlottesville’s failure to seek advice from others on how they had dealt with threats of violence in similar situations. And how the City and Virginia state officials had otherwise failed to train, prepare, and cooperate with one another, to effectively thwart threats posed by such events. Thus, violence ensued in Charlottesville on July 8. Those actions ignited a cascade of consequences that fractured the City, severely impairing its ability to deal with the larger and more dangerous protests on August 11/12. And those adverse impacts plague the City still.

This, I believe, is the central finding of the Independent Report. But why and how did this happen in Charlottesville? This needs further exploration.

Inexplicably, this failure occurred despite ample intelligence on the threat posed. CPD’s own intelligence gathering clearly predicted “that the July 8 event would likely be a large, confrontational, and potentially violent event … The sharing of all intelligence made (this) clear to all CPD personnel.” Some 600 to 800 counter- protesters, and up to 100 Klan, were projected to attend. Many would be armed. And the counter-protesters were known to be planning to shut down the event.

“For example, the Greensboro, North Carolina police shared with the CPD a flyer from social media advertising for (out of town) counter-protesters to (travel to and) attend the Klan rally in Charlottesville ‘to shut them down.’” The North Carolina police also suggested that squabbling within the Klan might significantly reduce the 100 Klan members earlier estimated to travel to Charlottesville for the rally. Both predictions proved highly prescient on July 8.

In addition, CPD’s own intelligence before July 8 was vastly superior to its total lack of awareness before the May 13 rally. But its local intelligence gathering on the plans of local activists opposed to the July 8 rally halted around June 23th. This was after CPD received a “strongly worded letter that accused the City police department of using ‘aggressive inquiries’ as ‘an intimidation tactic’ intended to curtail leftist speech and expressive conduct.” The local lawyer “representing a number of anti-racist activists and organizations in Charlottesville” who delivered this letter also held a press conference, alleging that CPD had tried “to interrogate City residents.”

In reply, CPD issued a press release saying that its investigation included all groups who planned to attend the Klan rally. The letter and its “accusations” (however) halted CPD’s efforts to gather information directly from local activists, hurting CPD’s intelligence gathering,” according to the Independent Report. In my view, this was also prescient as to the City’s lack of support for its own police department.

Other City efforts to dilute the threat of violence posed by the Klan rally were also met with resistance from the local community, all in different degrees. For example, “The City made a concerted and unified effort (branded Unity Day) to discourage attendance at the Klan event.” This included its work with local organizations to stage “counter events,” each at a different time and place, during the day of May 8.

Local clergy, however, recalled some resistance to “Unity Day” events. “(It) ‘rubbed people wrong’ as alienating and patronizing because some people felt strongly that they should confront the Klan and their hateful speech. These reactions among local citizens and groups were said by some ‘to create a division within the faith community, which only deepened after July 8.’”

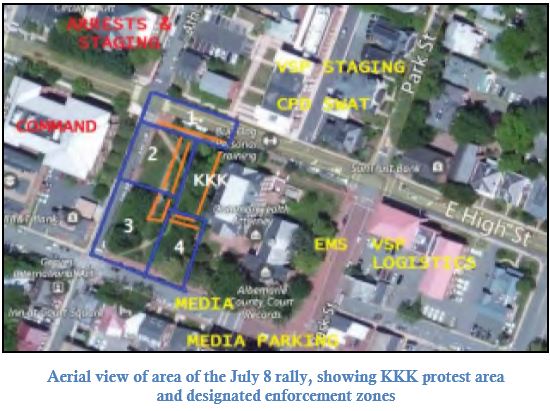

Nevertheless, the CPD did develop and deploy a “final Operational Plan that segregated Justice Park into five zones with the goal of separating the Klan and counter protester at all times. It provided a protected area between the Jackson Statue and the Albemarle County Circuit Courthouse for the Klan’s rally to occur. It placed Double barriers – or two rows of bike rack barricades spread 10 feet apart- (that) surrounded the KKK Zone on three sides with the Courthouse serving as the natural barrier on the fourth side. The remaining four numbered zones were established for the counter-protesters around the KKK Zone.” Recall, too, the CPD would escort the Klan from their parking lot behind the JDR Court to their KKK Zone inside Justice Park.

The Independent Report, however, suggests that this plan failed in its details, its lack of proper focus and emphasis on effectively dealing with those areas of greatest threat, and how those threats might arise and be prevented, particularly in keeping the counter-protesters and Klan sufficiently apart to thwart violence between them.

The Independent Report also suggests the plan failed to give all police elements – city, county, and state – the means and resources, including training, integration, authority, and mission clarity, they needed on site to carry out their mission effectively, namely to shut down the threat of violence before it could flare then spread, causing a array of collateral damage to the City, and its citizens as a whole.

Overall, too, the Report suggests the lack of sufficient local and state political will, and the concurrent failure on the state and local level to grant of the necessary authority and support that the local and state law enforcement personnel on the ground needed to properly do their job, namely to maintain the peace, and protect the safety of all involved (including themselves), while also enabling them to effectively safeguard the rights of speech and self-expression to all participants. Indeed, the Report suggests that this failure was ubiquitous throughout the City, its institutions, and its citizens, generally. Leaders failed to lead. Other citizens refused to follow, or stood passively aside, before and during the event.

Fortunately, some officers and troopers on the ground that day filled some of these planning, training, and resource gaps that opened, as their consequences loomed, before those officers and troopers in real time. This quick and competent action on the spot prevented much damage that easily could have become far worse that day. By then, however, much of the initial violence had flared and spread, doing lasting harm.

The Independent Report describes the City’s Operational Plan as it was to be deployed within the Five Zones, including the KKK Zone, roughly as follows.

The CPD police and Virginia State Troopers stationed in each of the four zones would not wear riot gear to avoid the appearance of “militarization.” Plainclothes detectives also placed within each zone would observe and advise outside officials, including the Command Center, and those within other zones, as to what was going on with the crowd. Officers there would “make arrests when appropriate for unlawful behavior.” Only the Chief of CPD was authorized to declare an unlawful-assembly.

If and when the Chief of the CPD declared an unlawful-assembly, this would be announced to the crowd and the officers within the zones would leave their zone and go to nearby buildings, where they would put on their riot gear that had earlier been stashed there, and then redeploy to other areas in need as directed.

If, after the declaration of unlawful assembly, the crowd failed to disperse ‘after an appropriate amount to time,” the Virginia State Police (VSP) mobile field force in riot gear would deploy to push recalcitrant protesters south out of Justice Park (thus away from the KKK Zone.) If, in that case, the crowd did not “remain passive and non-violent,” then tear gas could be deployed. Also, if necessary, the Albemarle County mobile field force, plus two SWAT Teams with Bearcats, that were otherwise held off site (and out of view) in reserve, could be deployed.

As will be discussed later, this plan and its implementation proved faulty in design, scope and execution. This was for many reasons, including lack of the necessary training, equipment, coordination, and cooperation among leaders, who failed not only to coordinate among themselves, but who failed to inform and train those all the way down the chain of command, to and including the most junior police officer.

For example, beyond the details that the Plan failed to address within the Zones, was the ugly fact that the greatest violence on July 8 occurred outside the five protected Zones. And that violence also happened in ways that the plan failed to anticipate, making those disturbances far more difficult to thwart or shut down once in play.

Indeed the harshest of that unanticipated violence in those unexpected places did not involve the Klan at all. It occurred only after the Klan had departed the scene.

Here too, the Independent Report suggests that this later violence was likely the cascade of earlier mistakes in the plan, violence that fed off earlier violence and its threat in and around the barricades within the zones. Hence, these later events too might have been avoided with a more effective and realistic plan well implemented.

Here’s a brief description of events as they directly involved the Klan before they left town on July 8.

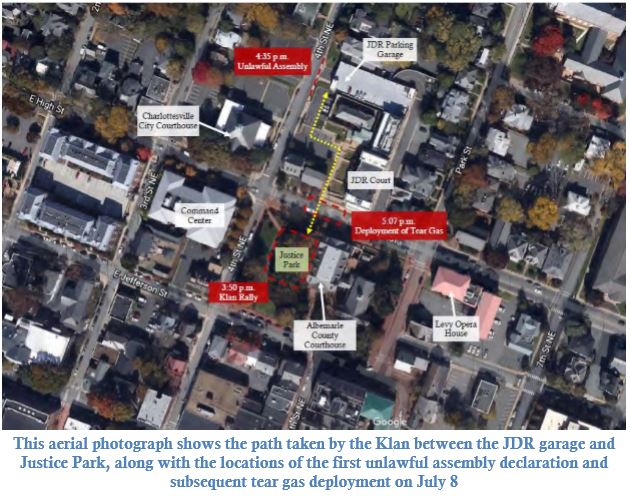

Events in and around Justice Park on July 8 began to unfold at noon. Violence there arose just before 3:00 p.m. It ended officially at 5:58 p.m. The Klan, however, did not arrive in Justice Park until 3:50 p.m. It arrived under attack. It held its rally there for 35 minutes. It departed the Park at 4:24 under attack until it took refuge in the JDR parking garage at 4:32 p.m. From there at 4: 44, it departed the garage under attack, but it managed with the help of law enforcement to escape and get safely out of town within minutes. The garage played a key roll in protecting the Klan, allowing it to organize with police help and escape. No Klan member was arrested on July 8. All those arrested appear to have been counter-protesters, mostly before the Klan arrived in town or after the Klan gained shelter in the garage at 4:32 p.m.

Here is a longer summary of what happened that day.

When, on July 8, the Klan’s 18-car caravan called the CPD at 2:50 p.m. to report that they were 15 minutes from the off-site rendezvous point, some 1,500 to 2,000 counter-protesters were already swelling and surging around the barricades encircling the KKK zone, awaiting the Klan’s arrival. Given these events, the Klan’s arrival within the park was delayed 50 minutes, until 3:50 p.m. The crowd within Justice Park, meanwhile, had been growing since noon.

These details noted in quotes below were taken from the Independent Report:

Around noon on July 8 people began to gather in anticipation on the Klan’s expected 3:00 p.m. arrival at Justice Park.

From 12:00 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. Justice Park “remained … peaceful with officers communicating with … “small groups of individuals arriving. ” One officer reported 15 individuals “carrying fire arms and/or knives openly” in Zone 4.” Others were donning counter-protester dress.

Around 1:30 p.m. more “opposition groups and various factions arrived … (and) continued to float between Zones 2, 3 and 4 … “it was peaceful at first.”

“A 1:42 p.m. multiple people were seen carrying firearms, knifes, and swords.”

By 1:50 p.m., the City’s Command Center across the street “estimated that 200 people were in the Justice Park. Starting at 2:00 p.m., the crowd size increased significantly … People began marching through the Park carrying signs, chanting slogans, singing, and using drums and noise makers.” Starting at 2:00 p.m., the crowd was estimated to have doubled within the next 12 minutes. “At 2:12, the Command Center estimated that 400 people were in the Park.” Opposition groups there “characterized by one CPD officer as “very organized” and “totally coordinated” … “wearing gas masks, padded clothing, and body armor.”

Another police officer recalled “being surprised at the planning by some counter-protesters who brought organized medics, used walkie-talkies to share information, and wore helmets, full body pads, gas masks, and shields, (and who were) actively monitoring scanners and other devices to track the movements and communication of police.”

Just before 3:00, the crowd’s size increased yet again. And the atmosphere intensified. At 2:56 p.m. “Zone 1 was full of marchers, counter-protesters, and bystanders” and “the streets surrounding the Park and adjacent sidewalks were filled up. The crowd, now anticipating the arrival of the Klan, had packed the zones with people who began pushing up against the barricades. This placed the police (in standard uniforms, without riot gear or other protection) in these now threatening public zones in “a terrible safety situation with their backs to people…”

This “terrible safety situation” caused CPD leaders to pull the police out of the Public Area now full of counter-protesters (namely Zones 1, 2, 3, & 4), and to order those police and state troopers (who were without riot gear and other protective clothing) between the two barricades, into the 10 foot wide space that separated the counter-protesters from the empty KKK zone that still awaited the arrival of the Klan.

This “terrible safety situation” no doubt substantially delayed the Klan’s arrival for some 50 minutes, until 3:50 p.m., and the terrible safety situation quickly spread.

“By 3:10 p.m., the counter-protesters had identified the area through which the Klan would enter Justice Park” so part of the crowd moved into that location along High Street in Zone 1. “At 3:16, about a dozen people locked arms (there at that location) on High street to form a human wall blocking the entrance to the Klan’s KKK zone.”

Seeing this blocking action, the “police by bullhorn warned these counter-protesters to move or be arrested.” The counter-protesters refused to move. At 3:18 the VSP mobile field force in riot gear moved “out of their staging area inside the JDR Court and prepared to clear counter-protesters blocking High Street.” At around 3:30 p.m., CPD police began to arrest those counter-protesters who, contrary to police orders, were still blocking the entrance route, while the VSP mobile force created a human corridor on High Street for the Klan to use (whenever they arrived).

Someone in the crowd filming the event later said: “that the police were overly aggressive in the way they arrested people who were simply standing in the way.”

Police said their actions to clear the blockage “fired up the crowd.”

Meanwhile, more counter-protesters, now again anticipating the Klan’s arrival, left their positions in Zones 2, 3, and 4, to flood the Klan’s access corridor though Zone 1. This growing crowd of counter-protesters were said to “nearly overwhelm the law enforcement in that zone.” One officer recalled that in the now flooded Zone 1, “we had to make some (more) arrests for blocking the entrance to the park, sidewalks. Another said (that) the crowd (there) in Zone 1 became ‘more agitated with the large majority obviously in opposition’ to the Klan” (who had yet to arrive.)

As a result, the barricades between the Zones were closed off, and even more “officers were removed from the crowd and placed inside the barricades.” The CPD later explained these movements of the police and troopers into protected areas “as an officer safety decision where the officers were severely outnumbered by the large crowd.” (Please recall earlier decision to clothe these police officers in regular uniforms instead of protective riot gear, a decision that now exposed them to rising threat levels while it also severely limited their ability to counter the rising threat.)

Meanwhile, two CPD squad cars with eight officers waiting at the secret site just out of town met the Klan whose caravan of 18 cars arrived there at 3:13 p.m. Now, with the Klan’s arrival there, the CPD Command Center across from Justice Park instructed their team at the secret site to hold the Klan in place there “as officers (downtown) cleared the Klan’s entrance on High Street.” Given the delay, the officer off site told the Klan that they would have “no time to fiddle around at the downtown parking lot.” “By 3:30 p.m., the 18-car Klan caravan started their drive into town, with a police car in the front and rear, not stopping for traffic lights along the way on a journey later described by the Klan Rep. as “dangerous and unsafe.”

Fortunately, a last-minute change by a sheriff’s deputy and police lieutenant allowed the Klan to park in the protected JDR Court parking garage, instead of its surface lot. This on-the-spot change in plans “saved a lot of issues … we were just lucky” … thank God we parked them in the garage, otherwise ‘we probably would have had to shoot someone’ to get the Klan out later,” police said later.

The Khan entered the garage at 3:39 p.m., and the garage door closed.”

Inside, the Police told the Klan to line up on foot and, once they had gotten outside, the Klan (now estimated to number between 40 and 60 individuals) were to “squeeze through” a narrow path in the crowd created by the VSP mobile field force.

“(We were) told to line up, stay together, and move quickly,” said the Klan Rep later.

The march started at 3:45 p.m. Many of the Klan members toted Confederate flags and wore Klan robes with hoods and exposed faces. Their journey on foot between the “human police wall of State Troopers” shielding them from the counter-protesters on High Street was later described by a Klan member:

“The counter-protesters gathered on both sides of the human police wall threw punches, launched bottles and fruit, and shouted ugly chants.” A bystander witness said the counter-protesters were “trying to jump over” the police in riot gear, yet “the VSP troopers remained very professional and non-confrontational.”

Once the Klan got into their KKK Zone at 3:50 p.m., many counter-protesters shifted back into the Justice Park’s public zones 2, 3 and 4, “pressing up against and reaching through the barricades.” The 10-foot space between the barricades was “too narrow, the counter protesters were right up on us,” said the Klan Rep.

The Independent Review reports that: “The crowd was most intense along the Barricade encircling the Klan. Farther away, the event remained largely peaceful. Some outside that Barricade area never felt a sense of danger.”

Indeed, it might be said that there were two rallies around Justice Park on July 8. One was chaotic along the barricades, and the other was largely peaceful nearby. Punctuated, perhaps, for some by a few scuffles now and then.

The Klan remained for 35 minutes in their KKK Zone, from 3:50 to 4:25. Several made speeches that often were muffled by the noise in the crowd. One police officer said that in his zone “no one crossed the barricades or … threw anything at the Klan … but that “it was so loud in our section no one could hear what the Klan was saying.”

A counter-protester carrying a BLM sign said they intended to be louder than the Klan so they could not hold their rally. Another said, “In addition to noise, counter-protesters launched projectiles at the Klan, including apples tomatoes, oranges, and water-bottles.”

Another CPD officer “reported that exchanges between the Klan members and individuals within the crowd were constant.” The City manager “received reports of some objects being thrown at the police, but there are no injuries.”

Another resident saw “people throwing bottles at the Klan” and Klan members “trying to provoke counter-protesters.”

Some in the crowd called the police ‘too aggressive.” They said that the police did not do enough to preserve the speech rights of counter-protesters. Others felt the police went out of their way to protect the Klan: “Even if I wanted to jump the barricades and attack the KKK, I could not.”

Another “suggested that the positioning of the police between the barricades was ‘unsettling’ because the police faced the counter-protesters with their backs to the Klan, giving the crowd the impression that the police were protecting the Klan while suspicious of the crowd.”

By this time, most all “eyewitnesses estimated that the Klan had 40 to 60 members while the crowd contained 1,500 to 2,000 counter-protesters.”

After the first 10 minutes of the Klan rally, at 4:00 p.m., the crowd began chanting for the police to shut it down. According to one, “the crowd was frustrated that the police allowed the Klan to exceed their time.” The police gave the Klan another 20 minutes, until 4:22. And the Klan did not object.

As the Klan started to depart at 4:25, many counter protesters shifted over to the designated Klan exit corridor that was still protected by the VSP mobile field force. Even then the Khan struggled to leave. One was punched in the face. Police reported they were spat on as the crowd threw tomatoes and water bottles.

And meanwhile “hundreds of counter-protesters surged down 4th Street to the JDR Court Parking garage where the Klan had parked.”

“Watching this unfold, a CPD Lieutenant and his team quickly moved to the front of the parking garage and spoke to the Albemarle County mobile field force stationed nearby. We knew we would need them and alerted them that the Klan was on the way.” At the same time the CPD Command Center moved officers from Zone 2 to the JDR Court garage to assist. These officers “lined up to maintain a separation between the Klan and counter-protesters, whose numbers continued to increase.”

The Klan holed up inside the garage at 4:30 p.m. as a large crowd of counter-protesters blocked their exit door from the garage. The Klan Rep. called it “terrifying;” they were “trapped inside.”

Around 4:35 the City and County police, State Troopers, and Sheriff’s Deputies lined up in front of the parking garage fending off the counter-protesters. The CPD lieutenant in charge, using a bullhorn, declared the crowd of counter-protesters an unlawful assembly. Within three minutes, at 3:38 p.m., a CPD Major seeing the lieutenant with bullhorn surrounded by counter-protesters took command and ordered the officers to assist the surrounded lieutenant.

“The Line of law enforcement personnel in front of the parking garage pivoted and pushed the crowd away from the garage door and across 4th Street. With the driving path cleared, the Klan exited the garage around 4:45 p.m. led by a CPD squad car.

The Klan Rep. said “the counter-protesters confronted the cars, hit them with weapons, and stood in our way,” despite the police escort, but all cars got away, and left the city, save for one that would not start, so it was left behind in the garage.

By all accounts, the crowd of counter-protesters became hostile to law enforcement. A former City Mayor, seeing the event, said, “that after the Klan left, ‘the counter-protesters turned on law enforcement’ and ‘things got crazy.’” Another participant, a clergyman, said “the ‘police became the enemy’ to many in the crowd, as people were angry that the police ‘protected the Klan.’” Another said, the “ ‘crowd turned against the police’ after the Klan left, partly because of the riot gear and aggressive actions of officers. Some crowd members chanted, “Cops and Klan go hand in hand.”

The events that occurred after the Klan’s departure, and their ramifications, would have a profound affect on the next white nationalist rally held on August 11/12, 2017, in Charlottesville.

In the next post, the third on the events surrounding the white nationalist protests against efforts to remove the Lee and Jackson, we will discuss what happened in Charlottesville after the Klan left on July 8, and how those events impacted the events of August 11/12.

Reed Fawell III, the former president of a Washington D.C., law firm, is a graduate of the University of Virginia.