Inova is betting that personalized medicine + big data can transform health care. Illustration credit: Richmond Times-Dispatch

Published this morning in the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

As Republicans and Democrats brace for a battle royal over Obamacare and what might replace it, they would do well to pay heed to an important experiment south of the Potomac.

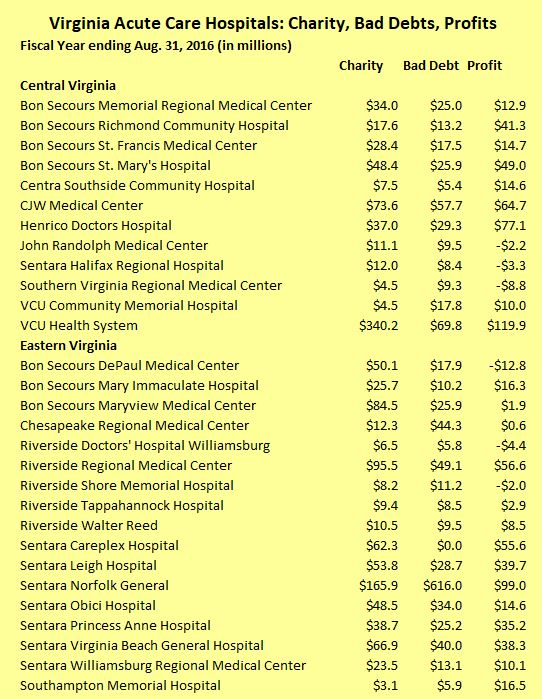

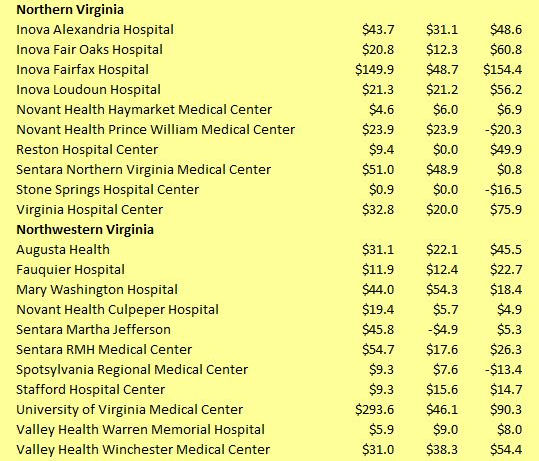

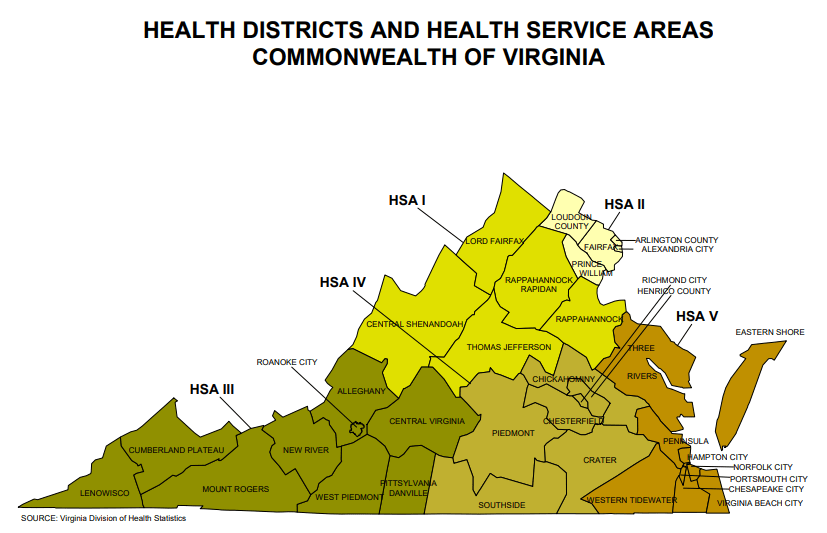

In Congress the debate centers on who pays for health care and how costs can be shifted to someone else — a zero-sum game. At Inova Health System, the dominant health-care provider in Northern Virginia, the focus is on improving peoples’ health at lower cost by practicing medicine differently. If Inova is successful, everyone wins.

The plan at Inova’s Center for Personalized Health, located across the road from Inova’s flagship hospital in Fairfax County, is to draw upon diverse data — electronic health records, user-generated data (such as fitness trackers and other wearable devices), family history, social milieu, and a patient’s genetic and biochemical make-up — to develop wellness and treatment strategies tailored to the individual.

“Take a cancer drug that’s effective 30 percent of the time,” says Todd Stottlemyer, CEO of the center. “A better way to understand it is that the drug is 100 percent effective for 30 percent of the people who possess certain genes or proteins.”

If physicians can target the treatment to the patient’s unique biochemistry, they can avoid giving drugs that don’t work. That leads to better health for the patient and saves society a lot of money.

***

Inova is building its Center for Personalized Medicine on the old Exxon-Mobil corporate campus, and adapting it for use as a medical research center. Construction is underway there for the Schar Cancer Institute, a multidisciplinary institute where precision medicine will be practiced.

The Inova Clinic will provide genomic testing and consultations. Other centers, institutes and incubators will conduct research, crunch data and, hopefully, spin off new business enterprises. Meanwhile, the Center has already begun recruiting national-caliber scientists.

Many other medical colleges and research centers around the country are doing similar things. What sets Inova apart is not just treating disease but keeping people well in the first place.

Let’s say a 48-year-old woman has breast cancer. Here’s how Stottlemyer sees things working: Physicians will want to understand her genetic make-up. They’ll want to know the biomarkers of the particular type of cancer she has. They will design a treatment, based upon the unique facts of her case, that will target the biomarkers and offer a higher probability of success than conventional approaches.

But the work doesn’t end there. What if the woman’s daughters have the same genetic markers? Should they screen more aggressively? Should they have mastectomies before getting the disease themselves? Inova will have genetic counselors trained in interpreting the scientific data and then walking patients through the complex decision-making process. Says Stottlemyer: “We want to empower good, informed choices.”

***

Inova will draw upon Northern Virginia’s strength in information technology. Harnessing so-called “Big Data” will help researchers and practitioners gain insight into not only individual patients but entire demographic groups.

The Center will cobble together health records, family histories, genome sequences, and sociodemographic statistics, and then compare the data against its database that houses more than 10,000 genome sequences from 134 countries of birth around the world.

The nonprofit health system is sinking hundreds of millions of dollars of its own money into the Center — acquiring the Exxon-Mobil building, funding venture capital, setting up the institutes and centers — and supplementing it with state dollars, philanthropic dollars, and funds from corporations and academic partners.

Late last year, Inova inked a $112 million deal with the University of Virginia School of Medicine allowing U.Va. medical students to participate in the discovery and commercialization of treatments for cancer and other diseases.

Stottlemyer sees the launch of a new center of research and innovation as a booster shot for Northern Virginia’s economy, which is still staggering under the impact of sequestration-related cuts in defense spending. Building bridges to U.Va., Virginia Tech, and Virginia Commonwealth University should provide a stimulus to downstate economic development, too, he says.

But the ultimate justification for a nonprofit enterprise like Inova to spend millions on an initiative like the Center for Personalized Health is to help the people of Northern Virginia and the commonwealth to enjoy better health at lower cost. When the center opens for business next year, health teams will disseminate insights from the center’s research to Inova hospitals throughout Northern Virginia.

The U.S. health care system is organized around treating people when they get sick, not keeping them well. “It’s a transactional system,” says Stottlemyer. Doctors and hospitals get paid only when they conduct a test or procedure or other service. “We’re trying to change the game.”

The capital projects section of the budget bill is often overlooked by the media. That has been especially the case this year, with all the major initiatives brought forth by the Democrats.

The capital projects section of the budget bill is often overlooked by the media. That has been especially the case this year, with all the major initiatives brought forth by the Democrats.