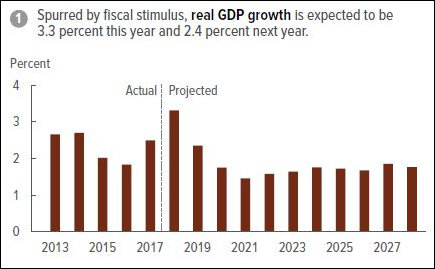

10-year economic growth — the critical variable. Graphic credit: Congressional Budget Office

In previous posts I have described the Republican-backed 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act as a Hail Mary pass, a gamble that by boosting economic growth the United States can outgrow the burden of chronic deficits and a rapidly accumulating national debt. I wasn’t optimistic, but I was willing to wait and see. After the passage of the most recent budget, which will increase spending and push deficits even higher, I became downright pessimistic.

Now comes the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) with its latest 10-year budget forecast, which takes into account the tax cuts and the latest budget. There’s plenty of gloomy news. But the damage isn’t as dreadful as I had feared. There is a glimmer of hope, although it is dim one.

First the bad news: CBO estimates that the deficit for fiscal 2018 will be $218 billion larger than what it had previously forecast. And it projects a cumulative deficit that is $1.6 trillion larger than the $10.1 trillion that it had previously prophesied for the 2018-2027 period. Debt held by the public (not including Social Security and Medicare trust funds) will rise from 78% of GDP to 96% by the end of the decade.

The CBO also struck a Boomergeddon-like tone by making the following points:

- Federal spending on interest payments on that debt will increase substantially, aggravated by an expected increase in interest rates over the next few years.

- Federal borrowing will reduce national savings. The nation’s capital stock will be smaller, and productivity and total wages will be lower.

- Lawmakers will have less flexibility to use tax and spending policies to respond to unexpected challenges.

- The likelihood of a fiscal crisis in the United States will increase. Investors could become unwilling to finance the government’s borrowing unless they are compensated with very high interest rates. If that happens, interest rates on the federal debt will rise suddenly and sharply.

As the football follows its trajectory into the end zone and a half dozen receivers stretch out their hands to catch it, the outcome of the Hail Mary pass is still “up in the air.” In less metaphorically strained words, the game isn’t over yet.

This CBO statement surprised me: While the federal budget deficit grows sharply over the next few years, later on, between 2023 and 2028, “it stabilizes in relation to the size of the economy, though at a high level by historical standards.”

That’s huge! The danger is that the national debt will grow faster than the economy, thereby posing an ever-increasing burden until the economy collapses. But if that burden stabilizes, even at a higher level, there may be hope that the U.S. can muddle through as (another bad metaphor alert!) the Baby Boomer pig moves through the entitlement pipeline. Eventually, a few decades from now, the entitlement crisis will ease and deficit spending will shrink.

The CBO assumes that tax cuts will goose economic growth this year but that growth will moderate in future years — from a peak of 3.3% this year to 1.8% by 2020, 1.5% for the two years after that, and 1.7% for the five years after that. But a plausible case can be made that a combination of deregulation and tax cuts will stimulate faster long-term growth, even in the face of the inevitably higher interest rates. If so, CBO would be underestimating growth and tax revenue. In this optimistic scenario, growth as a percentage of GDP actually could shrink and Boomergeddon could be averted.

On the gloom-and-doom side, the CBO also assumes steady-state economic growth over the next 10 years. But a recession could knock the props from under the growth projects, running up deficits, the national debt, and interest payments on the debt. Indeed, a major recession could trigger a full-scale fiscal crisis. The current business cycle is already almost 10 years old, one of the longest in U.S. history. What are the odds that it will last 20 years? Almost nil.

The key variable is the rate of economic growth. If it exceeds the CBO’s modest expectations, the U.S. has a fighting chance of avoiding Boomergeddon. If we see another black swan event — a trade war breaking out, North Korea firing a nuclear weapon, Iran blockading the Persian Gulf, the overheated Chinese economy imploding, a run on Italian banks, or a surprise insolvency in the hyper-leveraged, hyper-connected global economy sparking a financial panic — we could experience another 2007-scale recession — but this time with annual $2 trillion-a-year deficits. Hold on to your hats, people, it’s going to be a wild ride.