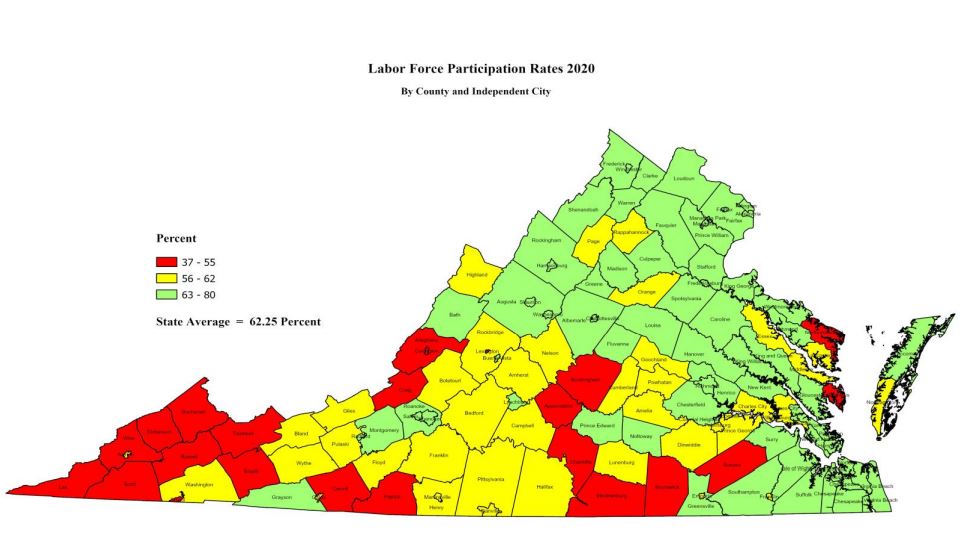

Labor Force Participation Rates, March 2021. Source: VEC Click for larger view. It represents the percentage of population of working age employed or seeking a job.

by Steve Haner

So many Virginia employers faltered or failed during 2020, the remaining companies may be charged a special tax of $95 on each of their own employees in 2022. It will cover the unemployment benefits paid to workers somebody else laid off, the highest so called “pool tax” ever imposed, more than double the amount collected following the previous recession in 2012.

The total unemployment insurance tax (average) may reach $360 per employee in 2022: A base tax of $249, the pool tax of $95 and a special “fund builder” tax of $16. That is more than 50% higher than the previous peak tax in 2012.

The figures emerged this morning as the Virginia Unemployment Commission staff briefed a legislative oversight panel on the financial health of the state’s beleaguered Unemployment Insurance program, swamped by a record number of claims in the COVID-19 recession and hampered by administrative failures in dealing with claims that needed extra attention.

For details, here is the UI Status Report presented today, following the usual format. VEC also provided more information on Virginia’s employment history over time, by region, industry, and locality.

The General Assembly can soften the tax blow by taking some of the massive inflows of federal American Rescue Plan stimulus funds and directing them to refill the depleted UI Trust Fund. That will be considered at the coming special session of the General Assembly, and some level of UI tax relief is expected. Covering that pool tax amount should be first priority, since it is taxing employers for somebody else’s failure.

Under a court order now to clean up the embarrassing claims backlog, VEC Commissioner Ellen Marie Hess reported that the remaining 70,000 cases in limbo should be addressed by early September. Legislators on the panel continued to report constant complaints from constituents who have been frustrated by the communication delays and difficulty in reaching VEC.

On average, the backlog works out to 700 claims per House district and 1,750 per Senate district. Be sure that federal officeholders are getting the calls from angry constituents as well.

A long-delayed upgrade to the VEC’s computer system, public interaction portals and communications system is due October 1. One legislator in particular, Del. Sally Hudson, D-Charlottesville, was sharply skeptical that VEC is doing that correctly and following best industry practices, a view that was reinforced by data expert Waldo Jaquith speaking during a public comment section.

Hudson, who teaches economics at the University of Virginia, has emerged as the most focused and forceful legislator on UI issues in the past three decades. The once-sleepy meetings of this oversight panel (which I have followed since 2002) have become interesting indeed because of this crisis and her willingness to probe. She is pushing to greatly expand the tracking and reporting into the future.

That’s problem number one, and the most pressing. Problem number two is the coming wave of tax increases on Virginia’s 235,000 employers. The state UI tax is an annual amount per full time employee. During good times the tax is low, and the UI Trust Fund grows fat, but once the Trust Fund drains below a certain point the taxes begin to rise. Employers also pay a federal UI tax per worker.

The base state tax an employer pays is based on its own history of layoffs, and with no history of claims the tax can be as low as 0.10 percent of the first $8,000 in pay ($8). With a bunch of layoffs, the tax reaches 6.2% of the first $8,000 per employee ($496).

The pool tax is the same for all employers, per employee, and it covers the money that VEC does not collect because other employers closed, as many did in 2020. Employer A fails and everybody else has to contribute to the benefits for its laid-off workers. The record pool tax expected for 2022 is a sign of how destructive this recession was and how long the workers remained off the job.

One reason the 2022 taxes are projected to be so high is that Governor Ralph Northam prevented VEC from increasing the taxes in 2021, as would normally have happened. That just delayed the necessary efforts to rebuild the trust fund, which likely will extend well past 2022.

The headline in the employment history report, which didn’t even get mentioned during the meeting, is how flat employment growth has been in Virginia during the 2010-2020 period. Partly that reflects the destruction of jobs during the pandemic, still well below pre-pandemic levels in many sectors. But growth was weak even before that sharp and deep recession, and wildly uneven across the state.

Total non-farm employment grew under 6% from 2010 to 2020, mostly in the Northern Virginia and Richmond regions. Winchester also grew a bit above the state average, but several regions lagged the anemic statewide figure. Look at what sectors grew over the decade (education and health and business services) and which diminished (construction and manufacturing and utility work) and you see the trends remaking Virginia.