by James A. Bacon

Silicon Valley may be the biggest fount of innovation and productivity in the American economy, but the oil & gas industry arguably comes a close second. Fracking entrepreneurs have boosted U.S. oil production by 3.6 million barrels daily in just the last four years and have deluged the country in natural gas. Many analysts fretted that the extraction of oil and gas from shale, which took off when oil sold at $150 per barrel, would become unprofitable under $100. But thanks to continued innovation, some operators say they can produce more profitably today at a price of $65 a barrel than they could at $95 a barrel three years ago.

Donald L. Luskin and Michael Warren suggest in the Wall Street Journal today that innovation could drive the profitability point even lower, writing, “The oil patch today is afire with the same technological imperative and competitive mission that has powered the U.S. electronics revolution—think Moore’s Law—to dash headlong down the learning curve, crushing costs and prices and making up for it in volume.”

The Marcellus Shale formation where much of this oil and gas production is taking place, skirts along the edge of Virginia. Only one finger of the formation runs through the Old Dominion, and much of that is in protected national forest. While Virginia is not likely to benefit much from the production of oil and gas, it can position itself as a consumer — of gas especially.

Natural gas is the most clean-burning of all the fossil fuels and it releases less carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than coal, which it has largely displaced in Virginia’s electric power industry under Environmental Protection Agency pressure to to meet tougher toxic emissions standards. The restructuring of Virginia’s electric power industry will continue under another round of EPA mandates to reduce CO2.

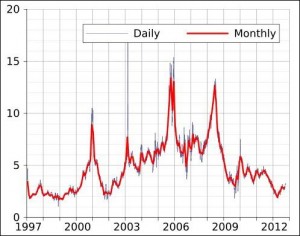

Natural gas prices at the Henry Hub in U.S. dollars per million BTUs. Source: Wikipedia

One of the big questions facing Virginia’s power companies and utility regulators is how much to depend upon natural gas. Gas is abundant and cheap now but historically it has been prone to wide cyclical price fluctuations, as seen in the chart to the left. If gas prices are likely to stay at their current low levels forever, it would be an easy choice to use gas as a base-load fuel, not just save it for power stations that can dial output up and down quickly to match fluctuations in demand for electricity. While coal and oil are out of favor as base-load fuels, due to pollution considerations, Dominion Virginia Power believes that nuclear is a viable alternative over the long run. Local environmental groups oppose construction of a third nuclear unit at the North Anna power station.

Dominion argues in favor of nuclear, in part, as a fuel diversification strategy. The more the state relies upon natural gas to power its electric turbines, the more ratepayers become vulnerable to spikes in gas prices. It is prudent to diversify fuel sources to include nuclear and even some renewables in the electricity-generating portfolio, the argument goes.

So, the question becomes, what are the odds that gas prices will spike as they have in the past? If export controls on natural gas are relaxed, and the U.S. begins exporting gas, could prices becomes more even volatile? Could Virginia electric power generation become too dependent upon natural gas?

Luskin and Warren argue that fracking has altered the economics of the oil-and-gas industry to make supply less volatile, which implies that prices will be more stable.

Wells in light tight-oil formations can be drilled and completed for millions—not billions—of dollars, and the majority of the estimated recovery will occur within a year or two of bringing it on line. Capacity across a diversified portfolio of wells can be turned on when future prices justify it, and off when they don’t. That turns upside-down the traditional model of oil megaprojects that require billions in upfront capital, years of lead time, and always-on production irrespective of price.

All this means that, for the first time in history, oil production is becoming a modern manufacturing process. The frackers are engaged in “just-in-time” production, analogous to the methods pioneered by Japanese manufacturers in the 1970s and 1980s, which led directly to hyper-efficient global supply-chain management perfected by Wal-Mart in the 1990s.

I don’t sense that public opinion full appreciates the extent to which fracking changes the rules of the energy game. Virginians need to incorporate these new realities into their thinking about energy policy.