Under prodding from the General Assembly that goes back years, Virginia’s four-year institutions are finally developing an easier path from community college to a bachelor’s degree. Unfortunately for students, it is spreading slowly. Unfortunately for anybody obstructing the process, there is one place where the full potential is being realized and proving the concept.

The dual enrollment and transfer relationship between Northern Virginia Community College and George Mason University is so seamless the community college students have GMU identification cards and access to GMU recreational facilities. The Nova Advance program works for 20 degrees with a goal of expanding to 50 possible degrees. Community college students have access to advising and other forms of support from the start.

Paying community college prices for two years saves $15,000 or more towards a bachelor’s degree. Also, before this process community college transfers often found they needed more credits than traditional students, adding additional and wasted cost. With the early guidance toward the right courses and firm agreements to accept the credits the standard 120 credit hours should now do it.

GMU Vice President for Academic Innovation Michelle Marks said getting this ready for launch this term “is the most complicated process I’ve ever worked on.” Hundreds of faculty members at both schools had a hand in course and program design. They planned to start with five degrees, but the enthusiasm pushed them way beyond that. “People wanted to do this,” she said.

There will be some lost revenue for both schools but the presidents of both see this as “right for the families and right for the students.” Marks said. The first 129 Advance students are in class now, with 189 more lined up to start in the spring. The long-term growth plan runs to four digits.

This past summer, Virginia Commonwealth University and the two Richmond community colleges announced they are working on a similar program, but on a smaller scale and limited to arts and humanities degrees. Previously about 75 students per year have switched from John Tyler or J. Sargeant Reynolds to VCU.

The new program will take three years to implement, with the first year (underway now) spent on evaluation and planning, and is supported by $2.4 million over the period from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It will be another year from now before students enter the pipeline.

Jeff Kraus of the Virginia Community College System mentioned three other working relationships, involving Virginia Tech, James Madison and the University of Virginia and their neighboring community colleges.

These examples do make a key point: What is working is a relationship between the four-year school and its neighboring community college or colleges, rather than a statewide, system-wide focus. “Community college students are not going to travel to the other end of the state to finish a degree,” said Sharon Morrissey, VCCS Vice Chancellor for Academic Services. The dream remains far more widespread portability of transfer credits from community colleges.

The General Assembly started pressing this forward years ago with the classic carrot, financial aid in the form of a program of scholarships for VCCS transfers to four-year programs. Those transfer grants have grown to almost $4 million per year, and the 2,500 students using them this term can receive up to $3,000 per year if seeking a science, technology, engineering or math degree at one of the major institutions.

But the theory behind the grants was not working so well in the real world. Transfer students were hitting barriers.

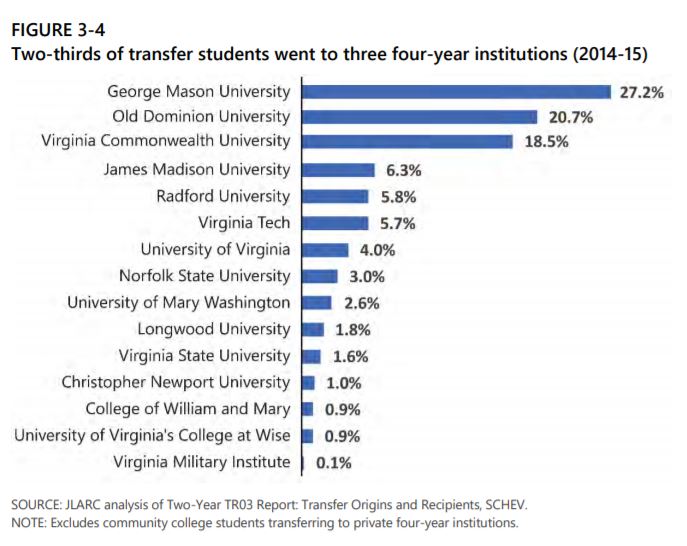

So in 2017 the stick was applied, in the form of a Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission Report that highlighted the problems students were having transferring credits from community colleges, or getting any credit for what were billed as dual enrollment programs in high school. It pointed out where the transfers were happening and where they were not.

Finally, the General Assembly stopped hinting and prodding and passed bills in 2018 directing more action in this arena.

Delegate Steve Landes, a Republican from Waynesboro and chairman of the House Education Committee, had House Bill 3, directing the State Council for Higher Education in Virginia to work on the dual enrollment problem. Senator Siobhan Dunnavant, a Republican from Henrico, sponsored Senate Bill 361 directing the community colleges to set up 15-credit and 30-credit pathways which would be accepted upon transfer. The burden of proof shifts and the four-year schools must demonstrate why they won’t accept them. The goal of every course being accepted everywhere remains elusive.

Implementing Dunnavant’s bill, which passed without any negative votes, is a major topic for next week’s State Council of Higher Education for Virginia meeting.

Morrissey came to Virginia four years ago from the community college system in North Carolina and admitted early frustration with the transfer process. Virginia had articulation agreements making it easier for community college students to get admitted to the universities, but getting the credits accepted was more of a challenge. The JLARC study quantified just how many extra credits the transfer students ended up paying for.

Pressed on whether the problem is just resistance at the four-year schools seeking turf protection, she insisted “we all do want to do it” and sees the transition “gathering strength.” The critical JLARC report and the legislation it spawned created “a big incentive for everyone to look at transfers differently.” While Virginia appears to be moving slowly, nationally it is one of three states getting recognition and additional grant support for expansion from the Aspen Institute.

If 2,500 students earning transfer grant scholarships and an initial cohort in the Nova Advance program of about 320 makes Virginia a national beacon of hope, that’s telling. But it is good news and there is plenty of room for it to get better.