About Bacon’s Rebellion

Bacon's Rebellion is Virginia's leading independent portal for news, opinions and analysis about state, regional and local public policy. Read more about us here.

Glogging Corridors

Is the McDonnell administration serious about protecting state highways from encroaching development? A dispute over a rural stoplight on U.S. 29 may tell the story.

by James A. Bacon

If you want to know how serious Virginia is about preserving the integrity of its major highways from development pressures, pay close attention to an obscure residential real estate project in Greene County.

In February the Greene County Board of Supervisors approved a rezoning for Creekside, a 400-acre residential development, with the condition that the developer build a $1.6 million connector road to U.S. 29 and a stoplight at the intersection. That stoplight would be located only a half mile from an existing light, reducing the speed limit on that stretch of road from 55 miles per hour to 45 and adding another slowdown on a highway officially designated a "corridor of statewide significance."

In February the Greene County Board of Supervisors approved a rezoning for Creekside, a 400-acre residential development, with the condition that the developer build a $1.6 million connector road to U.S. 29 and a stoplight at the intersection. That stoplight would be located only a half mile from an existing light, reducing the speed limit on that stretch of road from 55 miles per hour to 45 and adding another slowdown on a highway officially designated a "corridor of statewide significance."

Before the stoplight can be installed, however, the developer, the Fried Companies, must pay for a "warrant study" to determine if the signalized intersection is justified. After the study is published, the final decision to approve the signal will rest with the Virginia Department of Transportation's Culpeper district administrator.

The ruling is bound to be controversial, no matter what the outcome. The issue of access management is highly sensitive along U.S. 29 north of Charlottesville. Individual decisions like the Greene County stop light may seem small but over the years they have added up, rendering U.S. 29 increasingly unfit as an interstate transportation corridor.

The commonwealth of Virginia is sinking roughly $240 million into a controversial Charlottesville bypass, which will circumvent some 14 stoplights in Charlottesville and Albemarle County. The McDonnell administration approved financing for the project but admonished local governments to get serious about controlling access to the highway. Virginians should not continue the practices that made that investment necessary, Transportation Secretary Sean Connaughton told Bacon's Rebellion. "The definition of insanity [is] doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result."

The proposed stoplight would violate Greene County's comprehensive plan as well as VDOT's own access-management guidelines for U.S. 29, observes Brian Higgins, Greene Field Officer for the Piedmont Environmental Council. "It’s an opportunity for VDOT to apply their access management guidelines and show they are serious about it.”

But Ken Lawson, director of special projects for the Fried Companies, says the project has been in the works for years. Failure to approve the stoplight would redirect traffic emanating from Creekside's 600 single-family homes and 580 town homes to the so-called Sheetz intersection to the north. That intersection, he says, is "failing." VDOT is scheduled to make a $1.6 million improvement there but the intersection would be overwhelmed by Creekside traffic without a second stop light.

VDOT's district administrator is in the hot seat. If he approves the stoplight, he adds more plaque to the clogged artery of U.S. 29 and undermines its value as a major commercial corridor. If he rejects the stoplight, he contributes to localized congestion in Greene County. Pressure from local politicians and citizens can be hard to ignore.

A Long Brewing Problem

While the Creekside matter has come into focus only recently, the larger issue of preserving U.S. 29 as a major transportation corridor has been percolating for years. For decades, cities and counties along the highway treated access as a free good, allowing businesses and developers to build along it with little interference. Entrances, cut-throughs and stop-lighted intersections have proliferated without let-up. As long as transportation funds were abundant, the solution to the resulting congestion was building bypasses. Danville, Lynchburg, Charlottesville and Culpeper all have bypasses on U.S. 29. Warrenton has two. Charlottesville is about to build a second, and local politicians foresee the need for a third. Meanwhile, leapfrog development in rural counties like Greene, Madison, Culpeper and Fauquier threatens to gum up the highway in between metropolitan areas.

"Strip development, the proliferation of driveways and traffic signals, and the

overloading of traffic on a single roadway are all symptoms of a past approach that has emphasized exploitation rather than management of Central Virginia’s most important north-south transportation corridor," summed up the Rt. 29 Corridor Study, published in 2009. "This trend cannot be allowed to continue. It’s time to move forward. ... Land use and transportation planning should tie together to support the roadway’s functionality."

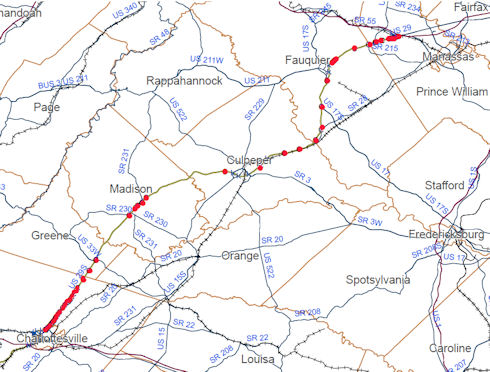

U.S. 29. Traffic signals between Charlottesville and Gainesville in 2009. Adapted from: "U.S. 29 Corridor Study."

U.S. 29. Traffic signals between Charlottesville and Gainesville in 2009. Adapted from: "U.S. 29 Corridor Study."

The study emphasized the need to limit access to the highway. "The development of properties close to Route 29, particularly in the portions of the corridor that have experienced high growth pressures, has resulted in the proliferation of access points. While serving the access needs for adjacent

properties, the proliferation of driveways degrades both the operations and safety of the roadway itself."

The study articulated a vision for Route 29 that would "significantly reduce the number of traffic signals on the roadway with an ultimate long-term goal of eliminating signals entirely."

Translating Words into Practice

So, what has happened since the publication of the 2009 study? That depends upon whom you talk to.

VDOT insists it has the problem is well in hand. The highway department has approved no new access points since publication of the 2009 corridor study, says Lou Hatter, public affairs manager for the Culpeper transportation district. "VDOT's statewide access management standards are being applied to the Route 29 corridor. These new regulations, such as standards mandating minimum spacing between traffic signals, are intended to provide some guidance and limitations on new access points and intersections."

Several years ago, VDOT worked with Fauquier County to close almost a dozen crossovers. More recently, VDOT has conducted a study, including aerial photography, of the access points within the Culpeper district. Further, Hatter cites Greene and Culpeper efforts to integrate access management into their comprehensive plans.

However, Dan Holmes, director of state policy for the Piedmont Environmental Council (PEC), says he has seen few tangible signs of progress. "You’ve got a whole lot of activity right now" that will further decrease the capacity of U.S. 29. Greene County staff, he says, is recommending approving new curb cuts and traffic signals. Culpeper County is dumping more traffic on the highway and adding new stoplights.

The PEC asserts that VDOT is not, in fact, doing much to curtail new access points. Referring to the Creeksize zoning petition, the PEC wrote the following in a Dec. 21, 2011, draft of a never-mailed letter to Connaughton:

In the recent review of a proposed rezoning in Greene - -a 400-acre development, Creekside -- VDOT raised no concerns about the proposal to add another signalized intersection on Route 29 less than 2,640 feet from an existing light. In fact, the applicant expressed confidence, based on his discussions with VDOT, that an exception on the spacing would be granted. ...

That instance, the PEC observed, was symptomatic of a broader pattern::

VDOT staff continue to weigh in on local projects ... allowing -- even requiring -- additional access points, crossovers, and at-grade intersections that destroy the capacity of Route 29 north of the proposed Northern Terminus of the Western Bypass. This lack of discipline and rigid restrictions regarding—or, rather, disregarding--access management principles is merely deferring to the future significant costs, funding shortfalls, and planning headaches for the Commonwealth.

But the problem goes deeper than VDOT, which finds itself in a position of responding to local zoning initiatives. Most counties along U.S. 29 steer growth to the highway with their comprehensive plans, creating pressure for more access points no matter how tight the controls. One example of how that happens can be seen in Madison County, a jurisdiction with 13,300 people.

When Zoning Administrator Betty Grayson moved to the county 37 years ago, it didn't have a single stoplight on U.S. 29. Now there are five. It's not as if the population has exploded. Rather, commercial development has gravitated to U.S. 29. Grayson cites the building of a McDonalds at one intersection. "Traffic increases. Accidents happen. What do you do?"

At least Madison is planning for its growth to occur in the town of Madison and a nearby community, not U.S. 29. But Albemarle County has designated the U.S. 29 corridor as its primary growth area, Greene County has made it one of its two growth areas, and Culpeper is planning to locate most of its commercial development along the highway. Traffic follows commerce, accidents follow traffic, and a clamor for stop lights follow accidents.

Grandfathered Mountain

Taming the access incursions is made even more difficult in counties bordering U.S. 29 by the fact that there is a veritable mountain of unbuilt projects with grandfathered property rights.

"The state has put into place new access management requirements and street acceptance requirements which should help improve the situation," says Stephen W. Williams, executive director of the Thomas Jefferson Planning District Commission. "But those have been in place only two years. ... The problem is the unbuilt inventory of projects approved years ago. There is going to be a lot of projects that will not be good for access management."

The options for curtailing access for approved projects are limited. "You can't go back and put restrictions on projects," says Williamson. "When you approve the site plans, you've created a right to develop on that property. ... Access rights to roadways is a property right just like everything else. Once those rights have been created, you can't impinge on them without legal consequences."

Tighter Controls

The PEC argues that the state must act much more aggressively to protect U.S. 29's capacity from encroaching development. Some recommendations from the draft letter:

- Whittle down the number of access points, at-grade intersections and crossovers.

- Downzone by-right rural densities.

- Require localities to adopt strict access management plans.

- Re-evaluate projects that have been approved but not yet built.

- Develop a coherent strategy to identify conflicts between land use and transportation plans. Use Entrance Corridor overlays to establish and enforce strict access management standards.

While the PEC's ideas may protect the integrity of the U.S. 29 corridor, they won't address local governments' needs. If counties don't encourage growth along their main transportation artery, where do they allow it?

That raises a host of issues that few rural counties have wrestled with. Should counties build parallel roads to handle local traffic? Should they, instead of smearing growth across the countryside and leaving VDOT to pick up the tab for road improvements, concentrate growth in urban enclaves, or villages, that can be served more cost effectively? Or should they, knowing that removing the implicit subsidy of free access to U.S. 29 would discourage developers from building in remote locations at all, prepare for a no-growth existence?

Transportation Secretary Connaughton concedes that more needs to be done. "VDOT is going to have to reach out to Albemarle County and other counties," he says. Because of the contentious controversy over the Charlottesville Bypass, the McDonnell administration has neglected access management in the Culpeper district. "We have to get back to the issue. It will have to be a joint effort with the central VDOT office, Culpeper district, Albemarle officials, and other counties. Once the Bypass controversy settles down it will be a top priority."

This article was written under a sponsorship of the Piedmont Environmental Council.