The twice-bankrupted Pocahontas Parkway: Virginia’s poster child for failed P3s.

by Randy Salzman

The history of American transportation “public private partnerships” indicates that virtually all P3 shell companies go bankrupt before paying back federal loans and the “private activity bonds” which they sold to finance part of the debt.

When these firms go bankrupt, who loses? Taxpayers. We get stuck (1) with paying back the money Uncle Sam lent the privates; (2) paying off bonds guaranteed by the state; and (3) picking up the maintenance costs. As a practical matter, the supposedly entrepreneurial, risk-taking private sector doesn’t take nearly as much risk as taxpayers do.

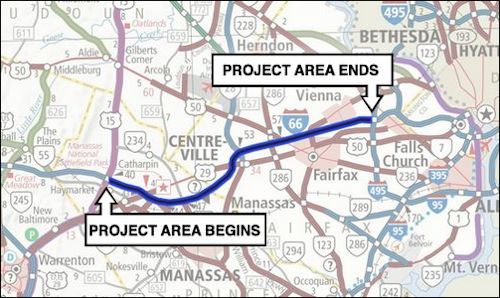

Aubrey Layne, Virginia’s secretary of transportation, recognized that his predecessor gave away Virginia’s transportation future with $6 billion (yes, with “b”) in 2012 through P3s. He has undoubtedly done a much better job negotiating Virginia’s latest P3, the I-66 project, but he’s a state official and has been interested in protecting Virginia taxpayers; not federal taxpayers. Most of us pay both state and federal taxes.

The I-66 partners are putting up over $500 million. Obviously, they expect to realize a profit or they wouldn’t have submitted the bid. That’s simple business and should underline, even if nothing else, what a horrifying reality previous P3s were for state and federal taxpayers. That 460 Mobility Partners put up zero dollars for the disastrous Suffolk-to-Petersburg connector under the McDonnell administration and walked away with $350 million is almost criminal.

The issue is especially timely now that President Trump is promoting public-private partnerships as a tool for increasing infrastructure spending and stimulating the economy. He has proposed $137 billion in federal tax credits for investors who commit to financing infrastructure, which would transfer even more risk from the private sector to the federal government.

The justification for P3s is that the private sector can build and operate projects more efficiently and economically than government can. But the public record is splotchy, and the news media needs to dig into it. In the U.S., more than a dozen billion-dollar transportation P3 projects have gone bankrupt. Even the Indiana Toll Road, the poster child for the privatization of transporation infrastructure, went belly up in 2015.

Cintra, which won the I-66 contract, went belly-up this spring with Texas SH-130, a toll road from San Antonio to Austin. Heavily promoted by former Texas governor and present U.S. Secretary of Energy Rick Perry, the project was absurd from the gitgo. The highway is located is only 20 miles east of an existing interstate, I-35. Even though Texas increased speed limits to the highest in the nation, few drivers were willing to pay tolls to use the road. SH-130 is so underutilized that airplanes have on at least two occasions landed on it! The project generated less than half the traffic and income that Cintra cronies projected when bonds were sold and federal loans obtained. Even though Texas bought down the tolls (wasting additional taxpayer dollars), Cintra’s shell company still went bankrupt and taxpayers were will be stuck paying off the bonds.

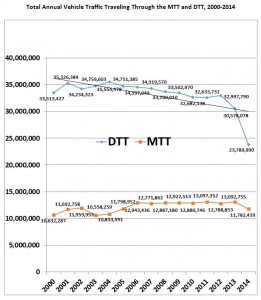

We taxpayers are told, pre construction, that tolls will pay off P3 bonds and back the notes. Even honest media such as The Washington Post parrot that line without examination. Yet no one can find a single instance in which a U.S. P3 toll road has generated the projected traffic or income. There is no bell curve of successes and failures that as one would expect if the forecasting of future traffic and future income was done correctly.

Inevitably, a few years later, after all the politicians and reporters have changed, the same excuse is given as the reason for the eventual bankruptcy: “For XXX reason, the drivers didn’t show up as expected and, reluctantly, the poor private had to give up the ghost.” Never do P3 advocates suggest that bankruptcy was the business model.

Here in Virginia, our first P3, Pocahontas Parkway outside of Richmond, has gone bankrupt twice (yes, twice) in a little over a decade. The owner: an Australian infrastructure company, Transurban. Since then, Transurban participated in the Capital Beltway Express public-private partnership. After CBE took in only one-fifth the projected tolls, the company had to restructure its debt on the project. Despite those negative experiences, Transurban is building the Interstate 95 HOT lanes and competed unsuccessfully for the I-66 project.

If Transurban keeps losing its shirt on P3s, why does it keep coming back for more? I cannot prove it, but I strongly suspect that the company hires the smartest lawyers and smartest financiers to structure the P3s so as to offload risk and ensure the company comes out whole regardless of what tolls are generated. The P3 contracts runs hundreds of pages, and I question whether anyone in the McDonnell administration truly understood them, or even read them as they farmed out negotiations to private law firms that proudly on their websites the great returns they got for private investors.. Continue reading