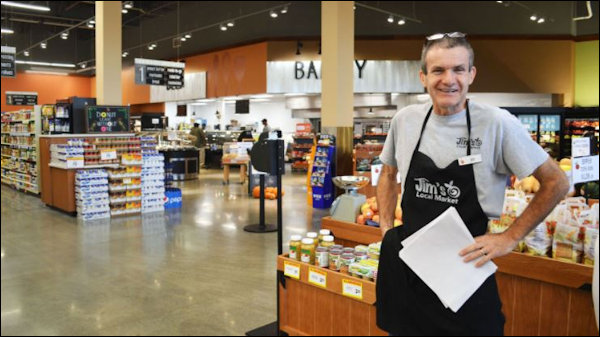

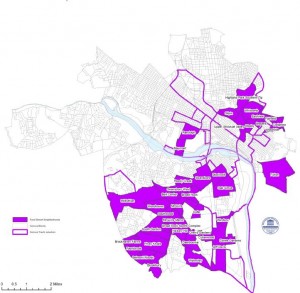

Food deserts in Richmond. Click to view larger image.

by James A. Bacon

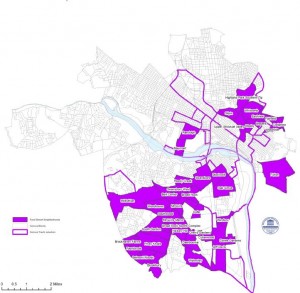

After two years of deliberations, a Richmond Food Policy Task Force has issued recommendations for tackling so-called “food deserts” in low-income city neighborhoods racked by obesity and food insecurity. I was anticipating a touchy-feely report full of good intentions divorced from real-world considerations. My worst fears were not confirmed. Although they were fiscally improvident, the proposals issued by the task force were restrained in their ambitions.

The task force does call for more spending, of course. How could it not? When government sees a problem, it invariably defines the solution as more government. Thus, the task force would spend $600,000 over two years to create a food hub/community kitchen, hire a food policy coordinator costing $100,000 yearly, hire two animal control inspectors to inspect urban chicken coops at a cost of $84,000 yearly, and expand healthier-school work groups at a cost of $100,000 a year.

On the positive side, there was a recognition that government also needs to get out of the way. The city should revise zoning laws that hinder urban agriculture and the raising of fowl, while also encouraging the conversion of vacant lots into community gardens.

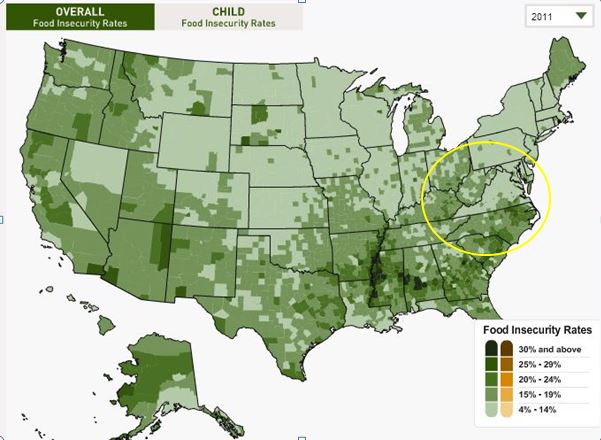

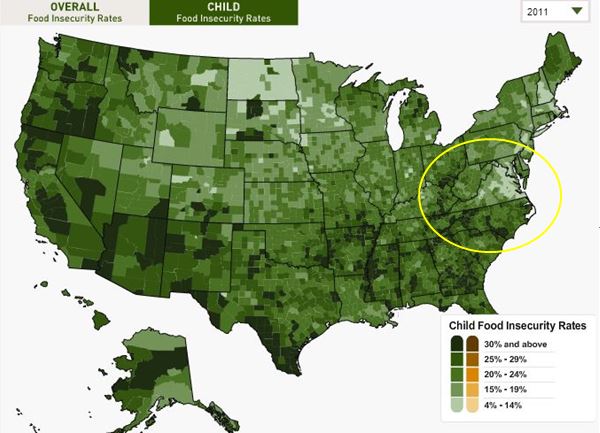

We can all agree that the problem is real. Residents of inner-city Richmond, like other communities across the country, have deplorable diets that are heavy in starch, salt, sugar and fat. Access to healthy food is difficult in many neighborhoods, especially for people who do not own cars. Obesity leads to poor health and higher medical bills, which society at large pays for.

The question is whether government can do much about the problem. The task force, which is comprised of community food advocates, city planners and public health officials, are inclined to believe that change is possible…. at least on the margins. Their solution: Grow and eat more fresh food.

That’s a wonderful idea. I’m not sure it justifies the expenditure of an additional $1 million a year in city funds, but it’s a wonderful idea. Indeed, it’s such a wonderful idea that the not-for-profit enterprises like Tricycle Gardens are already pursuing it. Whether the city can materially add to what Tricycle Gardens is already doing is anyone’s guess.

The problem in getting inner-city residents (or poor Americans anywhere) to embrace the production and consumption of healthy food is two-fold. First, people have lost the taste for fresh food and the knowledge of how to cook it. Second — and here I am swimming in the treacherous waters of political correctness, but it must be said — many poor people simply aren’t willing to expend the effort.

Over the past 100 years, the food industry has transformed how people eat. Americans of all ethnicities and income groups are totally disconnected from the process of growing and preparing food. Following market demand, the food industry has labored mightily to make food cheaper, tastier and easier to prepare. And it has succeeded. The big drawback is that food companies have made processed foods unhealthier. Along the way, Americans lost the taste for fresh food and the knowledge of how to cook it. If it doesn’t heat in a microwave, it’s too much trouble. You can give some people fresh food for free and they will not eat it. The problem isn’t one of supply or access, it’s that they don’t like the taste of fresh food or don’t want to make the effort to prepare it.

A revolt against processed foods has arisen over the past decade or so, but it is confined mainly to higher-income and better-educated classes who can afford to pay higher prices for food. Many of the urban farmers in Richmond are college-educated idealists. With the laudable exception of the 31st Street Baptist Church, which raises vegetables for its food pantry, the poor residents of Richmond’s East End have been slow to embrace either fresh food or gardening.

One would think that poor people would flock to the idea of urban gardening. It is their health, after all. And food consumes a disproportionate share of their incomes. Why wouldn’t they volunteer to help tend community gardens? Why wouldn’t they invest time and effort in cultivating key-hole gardens in back-yard planters? “Relief gardens” proliferated in cities across the country during the Great Depression as the poor, sometimes with philanthropic or government assistance, raised their own food.

But America is not the same country it was in the 1930s. Multiple generations of welfare have shorn many poor Americans of the habits, attitudes and ambition to organize and exert themselves on their own behalf. We can amp up nutritional education and put more fresh food in schools. We can organize school kids to get involved with gardening in the hope that they want to eat what they grow. Maybe we can erode the cultural preference for junk food. But we can’t force people to eat healthier, much less grow their own vegetables.

As Richmond Mayor Dwight Jones said, “This didn’t happen tonight, and it’s not going to change overnight.” He’s right about that. Whether city government can make a difference without tackling ingrained cultural attitudes remains to be seen.