Aubrey Layne explains the concept of fiduciary risk.

by James A. Bacon

As Transportation Secretary Aubrey Layne has had more time to dig into his job, he has developed an ever more nuanced appreciation of how things went wrong with the U.S. 460 Connector. There was more to the fiasco, which could cost the Commonwealth up to $300 million, than a simple failure to acquire necessary wetlands permits before opening the spending spigots and then discovering that the permits were not forthcoming. The McDonnell administration, he says, negotiated a public-private partnership deal without sufficient appreciation of risks entailed with the project.

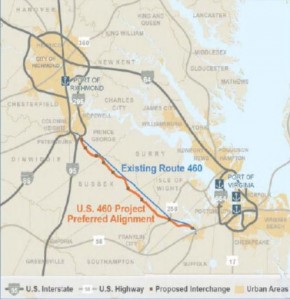

“I can’t tell you if they didn’t know they weren’t transferring the risk [to the private-sector partner] and got out-foxed, or whether they didn’t give a damn,” Layne told Bacon’s Rebellion in an interview today. Either way, the Commonwealth was left holding the bag when plans for the 55-mile Interstate-quality highway linking Petersburg and Suffolk had to be redrawn to do less environmental damage. He still hopes to recover some of the $250 million paid to U.S. 460 Mobility Partners (over and above $50 million in sunk design and engineering costs) for pre-construction work, but that outcome is uncertain.

Layne is optimistic that public-private partnership (P3) reforms enacted with bipartisan cooperation this year will prevent recurrences of the U.S. 460 debacle and help the state negotiate better terms in future deals than it got with the Interstate 495 and Interstate 95 express lanes projects in Northern Virginia, which effectively capped bus transit on the highways for the next half century. The McAuliffe administration’s big test will be to do a better job structuring the financing and risk of $2 billion in proposed improvements to Interstate 66 in Northern Virginia.

Before 1995, the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) had one way of building roads. It designed them, put construction out for competitive bids, arranged its own financing, operated them, maintained them and absorbed the risk of anything going wrong. The system got the job done but it had drawbacks. It overlooked potentially creative solutions to engineering and design problems, and it was prone to cost overruns. Then the General Assembly passed legislation enabling public-private partnerships, which provided the Commonwealth a whole new range of options for financing big projects and shifting selected risks to the private sector.

Facing a severe transportation budget crunch, the McDonnell administration made the strategic decision early on to use P3s to leverage scarce public dollars with private capital. From a high-level perspective, this made sense because the Commonwealth had limited capacity to issue road-building bonds without jeopardizing its AAA bond rating and then-Governor Bob McDonnell had not yet pushed through tax increases to bolster transportation funding. Moreover, the administration wanted to take advantage of historically low interest rates on long-term bonds.

But politics and ideology were pushing P3s as well, says Layne. There was a bias that something is always better if the private sector does it. Sometimes the private sector can do things better than VDOT, he says, and sometimes the private sector is better suited to take on certain risks than the state. But not always. The McAuliffe administration’s goal is to find the best fit — the best balance of cost and allocation of risk — on a case by case basis.

The devil is in the details. Layne, a Republican and a McDonnell supporter at the time, backed the governor’s mega-project funding priorities and voted to approve them while serving on the Commonwealth Transportation Board. Indeed, he chaired an independent bonding authority that issued bonds for the U.S. 460 project. But now that he’s transportation secretary, he realizes the issues were far more complex than presented to him and the CTB board.

The McDonnell administration first proposed a public-private partnership for the U.S. 460 project with the hope that outsiders could devise a more creative way of building and financing the highway than VDOT could come up with. Three consortia took a look and came up with similar conclusions — there would be insufficient toll revenue to finance more than a fraction of the construction cost with bonds. The McDonnell administration then switched gears, deciding to pay for most of the project with state funds but retaining the P3 structure in order to outsource the design and construction of the project to a private-sector partner, which turned out to be U.S. 460 Mobility Partners. The state should have gone back to square one and started over, says Layne, re-defining the project and putting it up for bids instead of using the P3 structure. Instead of getting multiple bidders to compete, the state wound up negotiating with a single player, U.S. 460 Mobility Partners. Even worse, Governor McDonnell had signaled that U.S. 460 was his highest priority, and there was no back-up plan — the administration had to reach a deal with U.S. 460 Mobility Partners or the project would never get built during McDonnell’s term. U.S. 460 Mobility Partners had all the bargaining leverge.

Negotiations took place within the P3 structure, which meant that the deliberations were secret and the contract not released to the public. VDOT briefed the CTB, the state’s transportation oversight board, but failed to disclose the information that critical wetlands permits had not been obtained and might not be obtainable.

The final contract for the U.S. 460 deal was more than 700 pages long. Layne says he can’t imagine than anyone in state government read the whole thing. “I’m confident that no one person understood it all. No one person could tell you what the deal was, what risk was transferred, and what risk the state was taking. And that’s a recipe for disaster” when negotiating with sophisticated business people on the other side of the table.

The dynamic would have played out very differently, says Layne, if the McDonnell administration had set up U.S. 460 as a design-build project. First, VDOT would have opened up the proposal to competitive bids, very likely getting a lower price even while the private contractor took on the risk of delivering the project on budget and on time. Second, VDOT guidelines would have ensured that all necessary permits were granted before the project commenced and the state started shelling out money.

Layne doesn’t blame U.S. 460 Mobility Partners for negotiating the best deal for itself that it could. It’s not a charity. The company’s managers had a fiduciary responsibility to get the best deal for its shareholders that they could. But elected officials have a fiduciary responsibility to the public. The challenge for the Commonwealth is to bring to bear an equally acute understanding of risks and rewards and to cut the best deal possible for the taxpayers. That’s where the state failed utterly with U.S. 460. If he’d had negotiated such a disastrous real estate sector when he worked in the real estate business, he says, he would have been fired.

Now it’s Layne’s turn. He has to structure a mega-project deal for I-66. Tomorrow, I’ll describe how he is approaching that task.

Who really establishes transportation policy for Virginia, the Commonwealth Transportation Board or the McDonnell administration?

Who really establishes transportation policy for Virginia, the Commonwealth Transportation Board or the McDonnell administration?