Trucks on I-64 at Afton Mountain struggle to maintain posted speeds on a grade that is half as steep as a short slope at the southern terminus of the proposed Charlottesville Bypass. How fast can trucks drive when starting from a dead stop at a traffic signal?

by James A. Bacon

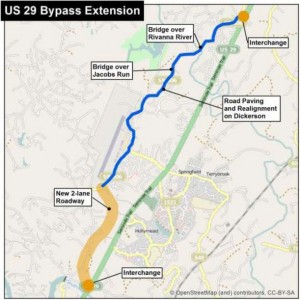

Spending roughly $240 million to build the Charlottesville Bypass will save motorists less than one minute of travel time compared to driving on U.S. 29, according to a new analysis by the Charlottesville-Albemarle Transportation Coalition (CATCO).

The installation of synchronized stoplights in 2007 has cut travel time on the congested stretch of stoplight-infested highway by 30% to 50%, and traffic volumes have increased less than predicted by the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) when the Bypass was originally proposed 20 years ago. At the same time, design changes to the Bypass made by winning contract bidder Skanska/Branch have diminished the performance of the highway, creating the potential for significant slowdowns at its southern terminus.

While some might dismiss the CATCO analysis as the work of a group that has long opposed the Bypass, it is the only travel-time analysis that anyone has conducted on the basis of published roadway design specifications. As the report notes, “VDOT has never publicly released any travel time information regarding the proposed Rt. 29 Bypass.”

Lead author Bob Humphris is a retired University of Virginia civil engineer professor. Having followed the Bypass controversy for 20 years, he has amassed the largest collection of Bypass-related documents anywhere outside VDOT. Last year he exposed the fact that the redesigned southern terminus would create safety problems (see “A Bypass Built for Trucks… that Trucks Won’t Use“). The Virginia Trucking Association subsequently confirmed that the safety issues he raised were valid, although the association still supports the project.

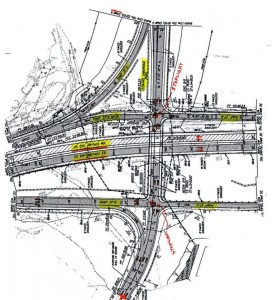

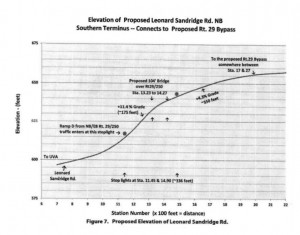

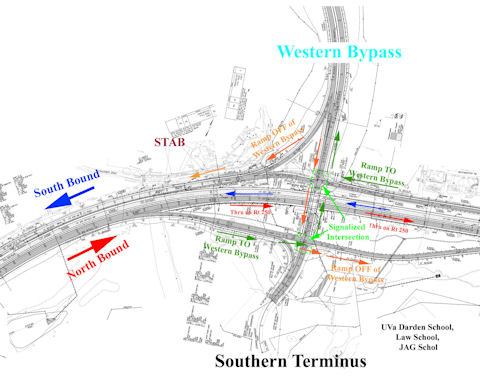

The preliminary Skanska/Branch design, which still may be modified under the design-build contract with VDOT, reduces travel time savings compared to the original VDOT design that was deemed too expensive. North-bound traffic from the U.S. 250 Bypass must detour onto a ramp and the local street system (Leonard Sandridge Road), which includes two stoplights, an 11.4% grade for a distance of 162 feet, and a 4.3% grade for 500 feet before entering the Bypass. States the report:

The CATCO-calculated travel time, using posted and estimated speeds for various segments, for the north-bound 6.56 mile Skanska design WITH the proposed Bypass is 8.26 minutes, and the calculated time for the 6.18 mile present route WITHOUT the Bypass is 9.11 minutes.

The CATCO calculation of a 51-second time savings comes with an important caveat. It represents an “ideal situation” in which traffic flows at the posted speed. In point of fact, even with synchronized lights, travel times frequently fall beneath posted speeds on the congested U.S. 29 business corridor. But Bypass travel times will fall short, too. North-bound tractor-trailers will encounter two stoplights at steep grades and, depending upon traffic conditions, could require multiple signalling cycles to get through.

Bypass foes have argued that for roughly the same price as building the Bypass, VDOT could make major improvements along the existing U.S. 29 that would alleviate more congestion and improve travel times for local traffic as well as for pass-through traffic. Albemarle County Supervisor Dennis Rooker also has been promoting the deployment of more advanced signalization controls on U.S. 29, such as those used successfully in a pilot project on U.S. 250 at Pantops Mountain.

Bacon’s bottom line: If the CATCO calculation is accurate, it would prove devastating to the economic case for the Bypass. The McDonnell administration has justified the project largely on the grounds that U.S. 29 is a corridor of statewide significance critical to the inter-regional movement of trucks. Likewise, the business communities of Lynchburg and Danville have supported the project thinking that it will make local manufacturers more competitive. But the notion that shaving 51 seconds off a five- to 10-hour trip to Northeastern markets would provide a measurable economic boost to Southside manufacturers is hard to maintain. That time savings would quickly be swamped by the ongoing encroachment of cut-throughs and stoplights along the length of the U.S. 29 corridor.