Virginia’s infrastructure deficit, though not as big as that of many other states, still represents a multibillion-dollar liability.

I have often opined on Virginia’s hidden deficits — fiscal time bombs in the form of budgetary gimmicks, pension under-funding, and deferred infrastructure maintenance. These problems are national in scope, and Virginia has been somewhat less derelict in its duty than other states, but sooner or later the Old Dominion will have an ugly confrontation.

The 2017 Infrastructure Report Card conducted by the American Society for Civil Engineers (ASCE) rams home the message. The U.S. overall infrastructure rates a D+ rating. Virginia-specific infrastructure rates a C-. (For whatever reason the 2017 national report card links to the 2015 Virginia report card.)

Here’s a summary of the ASCE’s run-down of major infrastructure categories.

Bridges. Virginia has 20,977 bridges and culverts, and their overall health is in decline due to age and lack of funding. Fifty-six percent are approaching the end of their 40-year anticipated design life. Some 30% are more than 50 years old. In 2013, 23% were found to be either structurally deficient or functionally obsolete. “Available funds are often used to address immediate repair or replacement needs, leaving few remaining funds for preventative maintenance. … The statistics indicate an impending peak of replacements which may be required within the next 10 years.”

Dams. Virginia’s dam inventory continues to grow older and more susceptible to damage. The majority were built in the 1950-75 era, and their average age is 50 years old. Of the state’s high-hazard dams, 45% have conditional certificates, indicating that they do not meet current safety standards. The rehabilitation cost for high- and significant-hazard dams is estimated to be $392 million.

Drinking water. Virginia has 2,830 public water systems supplying drinking water to more than 7 million Virginians. A large number of these systems have passed 70 years in age. The Environmental Protection Agency’s latest assessment showed that Virginia waterworks need nearly $6.1 billion over the next 20 years. “Deferral of the necessary improvements has worked so far, but can result in degraded water service, water quality violations, health issues, and higher costs in the future.”

Parks & recreation. Park attendance in Virginia is on the rise, and state parks are consistently ranked as some of the best in the nation. The ASCE commentary vaguely states that “a lack of commitment to adequately fund and maintain our facilities will change things for future generations.”

Rail and transit. The report focuses mainly on the inadequacies of funding for passenger rail, which must share rail lines owned by railroad companies that give their own commercial traffic priority. Virginia did recently set up a Rail Enhancement Fund, and it created an Intercity Passenger Rail Operating and Capital Fund, although it did not actually put any money into the latter. “The current funding is not sufficient to meet the increasing demand for rail and passenger service or to complete the much-needed rail infrastructure improvements and upgrades.”

Roads. The condition of Virginia roads is tolerable from a maintenance and safety standpoint, but traffic congestion in the Washington and Hampton Roads metropolitan areas has a huge negative economic impact. The average Washington-area commuter experiences 74 hours a year of delay. Despite an increase in transportation funding in 2013, “a network that has grown by 14% over the last 35 years and with every dollar buying less construction work, more funding is needed to maintain safe roadways while adding needed capacity, making this a high priority for Virginia.”

Schools. More than 1,800 public school buildings serve Virginia’s K-12 students. A comprehensive 2013 analysis found that 60% of schools are at least 40 years old. Estimated renovation costs exceed $18 billion for schools more than 30 years old.

Solid waste. Virginia’s solid waste infrastructure is in “good” condition. Increased recycling, a reduction in out-of-state waste, and the addition of 11 additional waste facilities have increased the state’s capacity from 20 years to 22 years.

Stormwater. About one-third of Virginia’s stormwater infrastructure is more than 30 years old, and much of the remainder was built 25 to 30 years ago. Most stormwater infrastructure has a 50- to 100-year lifespan. But the ASCE report is not impressed. “There are shortcomings to address for state-level, standardized reporting, public education, and ensuring a dedicated source of funding commensurate with the economic benefits of a healthy Chesapeake Bay and Virginia ecosystems.”

Wastewater. Virginia has $6.8 billion in wastewater needs over the next 20 years, a 45% increase from ASCE’s previous report card in 2009. That includes $1 billion for combined-sewer overflow, and much more to achieve Chesapeake Bay clean water standards. “Virginia has made progress with considerable investments and has a comprehensive plan, but has tremendous challenges ahead.”

I don’t share the ASCE’s sense of urgency for every category. If we want to reduce traffic congestion, there are alternatives to building more road and transit projects: (1) reforming land use to provide a better balance of jobs, housing and amenities, and (2) accelerating the Uber-ization of ride sharing in order to reduce the number of single-occupancy vehicles on the road. I also question whether 40 years is an appropriate standard for rehabilitating or replacing school buildings. Clearly, many schools need rehabbing, but the study may overstate the number.

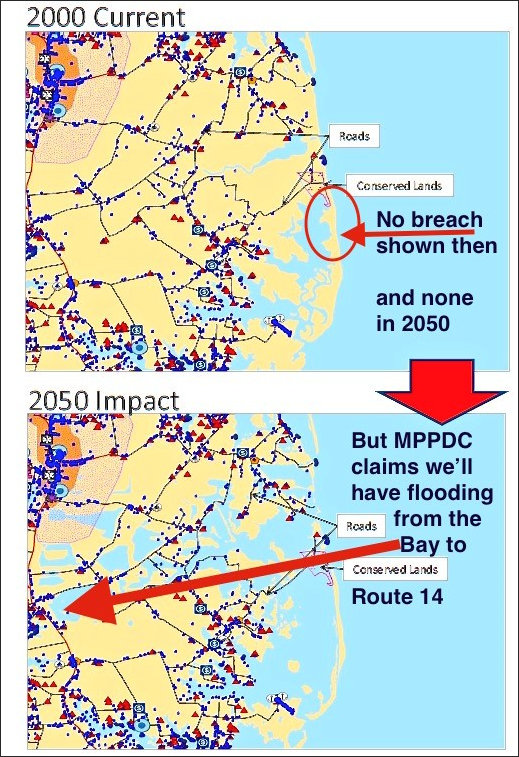

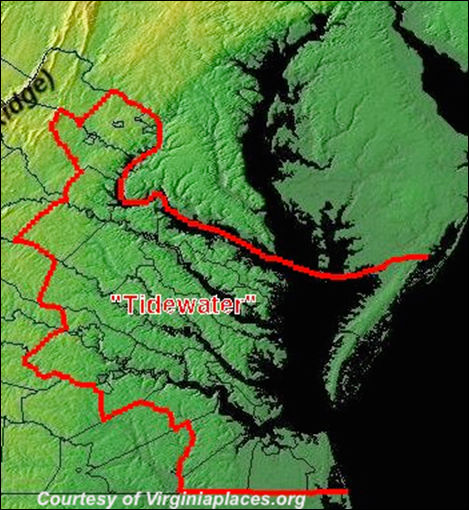

Even with these caveats, Virginia’s infrastructure deficit runs into the billions of dollars. And this analysis does not address recurrent flooding, an increasing problem in Hampton Roads. On top of all the other issues mentioned above, hardening the region’s infrastructure will cost billions of dollars of dollars more.

Update: Charles Marohn over at the Strong Towns blog eviscerates the ASCE report, which he describes as a “propaganda document.”

The reason why we can’t maintain our infrastructure is not because we lack the money or are afraid to spend it. It is because the systems we have built and the decisions we’ve made on what is a good investment are based on the kind of ridiculous math you see reflected in this ASCE report. We spend a billion here and a billion there and we get nothing but a couple minutes shaved off of our commutes, which just means we can build more roads and live further away from where we work. (Or, as we call that here in America: growth.)

Sixty years of unproductive infrastructure spending later, we are awash in maintenance liabilities with no money to pay for them. This is what happens when you have a government-subsidized, Ponzi-scheme growth system that, at all times, lives for the next transaction. America is all about new growth, which is why we don’t even bother to question the findings in a study like this.

Hamilton Lombard with Demographics Research Group at UVA said in the StatCh@t blog :

Hamilton Lombard with Demographics Research Group at UVA said in the StatCh@t blog :