There’s a new wrinkle in the Charlottesville Bypass controversy. The bridge across the Rivanna River may prove to be far more expensive than anyone anticipated.

By James A. Bacon

The Charlottesville Bypass could cost a lot more than the $197 million approved by the Commonwealth Transportation Board (CTB) last week, contends the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) in a statement released earlier today. The preliminary design work for the controversial road project, undertaken years ago, did not take into account the fact that the Bypass would cross the Rivanna River at the same spot as a proposed extension of Berkmar Drive.

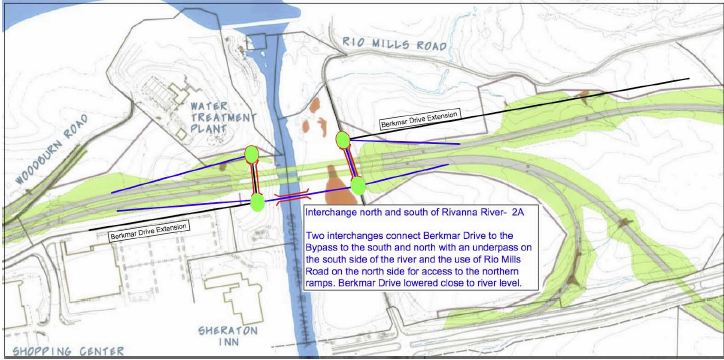

SELC based its claim of potential cost overruns on an analysis by Michael J. Wallwork, a professional engineer with Florida-based Alternate Street Design, P.A. Design considerations will be more compelex than originally envisioned because the Bypass and the Berkmar extension have to pass through the same chokepoint, threading between U.S. 29, a water treatment plan and a major subdivision. “The three main options … face significant cost, engineering, and other challenges due to the number and length of bridges and under or overpasses needed,” Wallwork wrote. “These challenges underscore the need for careful consideration of the costs and impacts of the proposed Bypass on the planned Berkmar Drive Extended.”

Wallwork's analysis complicates the decision-making of the Charlottesville-Albemarle Metropolitan Planning Organization, the approval of which is needed for the project to proceed. The report highlights the need for additional information rather than rushing the controversial 29 bypass through the approval process, the SELC argues.

"This is further evidence that the [Albemarle County] Board of Supervisors and MPO are lacking key pieces of information about the bypass and its impacts," said Morgan Butler, director of SELC's Charlottesville-Albemarle Project. "The public has been promised that the bypass would help advance Berkmar Drive Extended, a top priority in the county's Places29 master plan. But today's report indicates the opposite may be true, even if the two projects share a bridge. Our local leaders need to get a much better grasp on how the bypass would impact Berkmar Drive Extended before they vote on it, not after."

The MPO is scheduled to meet Wednesday night to address the western bypass issue.

One of the bridge scenarios in the Wallwork report.

The Bypass long existed as a line item in the state’s Six-Year Plan, but no money had been allocated to it and nearly everyone had written it off. Partial rights of way, acquired more than a decade ago, are due to revert to the original owners if construction doesn't get underway by 2012 -- effectively killing the project. But the McDonnell administration surprised the project's foes by resurrecting the Bypass earlier this month, persuading the Albemarle County supervisors to reverse their previous opposition earlier this month and then gaining the approval of the state transportation board last week.

Rodney Thomas and Duane Snow, two of the Albemarle supervisors who voted in favor of the project, also sit on the five-person MPO board. A third member is James Utterback, Culpeper district administrator for the Virginia Department of Transportation, answers ultimately to Secretary of Transportation Sean Connaughton, who has worked extensively behind the scenes to move the project forward. The two other board members, who serve on Charlottesville City Council, are widely presumed to oppose the Bypass.

Between Thomas, Snow and Utterback, the pro-Bypass forces would seem to have a majority on the MPO board. But there’s a complication. Thomas and Snow say that they switched their opposition to the project only because Connaughton promised them funding for four key U.S. 29 projects – a widening of the highway north of the proposed Bypass terminus; a new ramp at the interchange of U.S. 29 and U.S. 250 (widely referred to as the Best Buy ramp); completion of Hillsdale Drive, a road running parallel to U.S. 29; and the Berkmar extension, another road running parallel to U.S. 29 – in addition to the Bypass.

“When Duane Snow and I started on this, we were called by Sean Connaughton to have a meeting,” Thomas explained. “We were asking for money to widen U.S. 29. He threw the idea of the Bypass on the table. Duane and I looked at each other, ‘Hmm, what’s this?’”

The two supervisors responded that they were committed to the four “doables,” high-priority projects that were inexpensive enough that local officials believed they could gain funding, in contrast to the Bypass, which was widely believed to cost too much money. Most of the “doables” were integral to the Places 29 plan, developed as an alternative to the Bypass. Places 29 envisions reducing congestion in the U.S. 29 corridor north of Charlottesville through a combination of spot transportation improvements, more compact, walkable development and mass transit. An additional “doable” is a project to rebuild the Belmont Bridge in Charlottesville.

According to Thomas, Connaughton then asked the two supervisors, if he could get the funding for all the doables, plus the U.S. 29 widening, would they support the Bypass? They said they would. With the understanding that they could, in effect, have their cake and eat it, too – get funding for the Bypass and the four U.S. 29 improvement projects – Thomas, Snow and a third supervisor reversed Albemarle County’s opposition to the Bypass.

Several days later, Connaughton persuaded the Commonwealth Transportation Board to fund an additional $197 million for the Bypass (over and above funds already spent on preliminary design and right-of-way acquisition) plus $33 million for the U.S. 29 widening. The CTB did not approve money for the Berkmar extension, the completion of Hillsdale Drive or construction of the Best Buy ramp, however.

Noting that Albemarle’s support for the Bypass was contingent upon funding for the local transportation projects, the SELC urged the county to spell out the legal conditions and vote on them before the MPO meeting Wednesday. “It is essential that the county [has] clear, firm and legally enforceable conditions in place as part of any vote to amend the Metropolitan Planning Organization’s transportation plans to allow funding for the bypass. You cannot give up your one point of leverage and simply hope that the commitments will be met,” wrote the SELC’s Butler in a letter Friday.

One of those conditions was that the bridge for the Bypass over the Rivanna River would be designed and engineered to serve Berkmar Drive Extended as well.

The cost of the promised U.S. 29 improvements is estimated to be about $80 million, not including the expense of the Bypass. VDOT has yet to identify a source of funding for the other U.S. 29 projects. While the CTB found money for the Bypass and the U.S. 29 widening by raiding one VDOT fund reserved for public-private partnerships and another for matching future federal funds, it is not clear whether those sources can be tapped for another $50 million.

The funding gap could widen if the Bypass proves to be more expensive than projected. There has been no traffic engineering study for a decade, considerable right of way remains to be purchased, and VDOT never completed a final design. “This thing is not ready to go,” says Trip Pollard, a senior attorney with SELC. “They plucked it out of the deep freeze.”

There is no way to get an accurate cost for the Bypass yet because many design decisions have yet to be made, Pollard says. The northern terminus, where the Bypass joins U.S. 29, has yet to be engineered. Even more problematic is the bridge across the Rivanna River. According to Wallwork’s analysis, there is no elegant solution to the need to squeeze the Bypass and the Berkmar extension through the same slot. One possibility is for the two roads to share the same bridge, but that would defeat the objective of keeping the Bypass separate from local streets. Another option would be to create a two-level structure with one of the bridges running above the other. Complicating matters is the necessity of building extensive ramps, which will entail significant right-of-way acquisition in an area that has been partly developed.

“Under any scenario,” wrote Wallwork, “trying to fit two facilities in this space would be difficult and extremely expensive."

=============

This article was reported and written thanks to a sponsorship by the Piedmont Environmental Council.