|

PART

I of THE PROBLEM WITH CARS laid out the basic

premise:

It

is a physical and economic impossibility for

Autonomobiles to provide Mobility and Access

for the majority of US of A’s citizens in

the 21st century.

PARTs

II and III examined two contexts – recreation

and entertainment venues (PART II) and Big Box

facilities (PART III). These explorations

provide compelling evidence of the need to

fundamentally rethink extensive use of

Autonomobiles to achieve Mobility and Access.

PART IV further explores the basic disability of

Autonomobiles raised in PART I:

The

space required to drive and park Autonomobiles

disaggregates human settlement patterns. The

resulting distribution of land uses is grossly

dysfunctional for the vast majority of human

economic, social and physical activities. The

autonomobile is an economic and physical

option in few circumstances and for very few

citizens even those at the very top of the

economic food chain. (See End

Note Thirty-nine.)

A

Picture Is Worth a Thousands Words

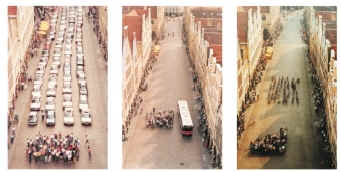

On

10 January 2008, the Urban

Richmond blog published three side-by-side

photos originating from the City of Muenster

Planning Office. These three pictures are worth

far more than 3,000 words.

The

graphic contrasts the street space needed for a

standard urban bus full of passengers (center)

with the space required for the same number of

people using Large, Private Vehicles (left) and

for the same number of citizens using bicycles

(right).

The

three photographs provide a low oblique

perspective of a street, presumably in

Muenster, that tells the story of Autonomobile

spacial requirements very clearly.

This

is not a new idea. Joe Passonneau published a

sketch showing this relationship in the '70s.

(See "Space

Hogs," on the Bacon's Rebellion

blog.) An

Agency staging its own version of this graphic

demonstration in every New Urban Region

reinforces the importance of the excessive

spacial demands of Autonomobiles in settings

with which citizens of that specific New Urban

Region can identify.

Another

way to make the point that Automobiles are

space hogs is to look at an aerial photo of the

Zentrum of any component of human settlement

pattern from Village scale to New Urban Region

scale. Parking lots and streets take up most of

the space.

A

central problem in trying to build citizen

understanding of human settlement patterns is a

lack of useful graphics. Most citizens cannot

visualize what the settlement pattern might look

like even in the shared-vehicle station area.

The

first image of “higher intensity” that comes

to mind for most citizens is “Manhattan”

which is inappropriate and misleading, except

for a small part of Manhattan itself. A second

problem is that few can “read” the wealth of

economic, social and physical information that

an air photo – or any view of the urban

landscape – can convey. This is an important

part of geographic illiteracy.

Once

TRILO-G is published, S/P will devote special

attention to graphic representations of

functional settlement patterns. It is maddening

that there is no interest in supporting these

graphics. Architects who are trained in drawing

streetscapes want to feature and promote their

buildings. Urban Designers like to feature

streetscapes that are interesting but not

definitive. The graphics paid for my the

shared-vehicle system equipment suppliers and by

shared-vehicle system Agencies feature the

rolling stock and the platform. Urban space

functions best when these elements are not

visible in a panoramic view of a station area.

(The problem of visualization is addressed in

“All

Aboard,” 16 April 2007.)

Learning

from Horses

When

writing The Shape of the Future we

examined the experience of urban citizens with

pre-Autonomobile modes of travel to illustrate

the importance of the excessive amount of space

taken up by Large, Private Vehicles. Here is the

way we expressed this issue in Chapter 13 Box 9

which has been updated to reflect the Vocabulary

in the current version of GLOSSARY.

The

Carriageless Horse

Horses

have been part of the evolution of urban

civilization for 10,000 years. Horses were

(and are) consumptive and expensive to

maintain, and so for most of this period,

horses have been limited in ‘high

value-added’ activities. These activities

have included waging war, ceremonies as well

as transport and recreation of those at the

top of the economic food chain.

When

large groups of humans - e.g., those living on

the Steppes of Central Asia or on the High

Plains of North America - wanted to (or were

forced to) take advantage of the speed and

range that the horse provided for more than a

few in a clan, tribe or community, the humans

were required to move to very low density

settlement patterns in order to provide

pasture/feed for the horse and to dispose

of/avoid piles of horse manure.

Extensive

use of the horse to provide Mobility and

Access for the entire population required a

density so low that these clans and tribes

became nomads and/or mobile raiding parties

because they could not support themselves and

their horses in some more amenable pattern.

The

pattern of human settlement that physically

accommodated the widespread use of the horse

proved to be less desirable from an economic

and social perspective than an alternative

pattern which forsakes regular use of a horse

for most adults.

Humans

found it more desirable from economic,

social and physical perspectives to live in

settlement patterns where citizens did not

need to use the range and speed of the horse

in order to carry out their everyday

activities.

Horses

made another run at impacting human settlement

patterns early in the Industrial Era. The

steel wheel and the gravel crusher made

horse-drawn omnibuses, coaches and buggies

useful vehicles to meet some urban needs. The

rising affluence and expansion of the Middle

Class, coupled with the conversion of

pre-industrial ‘cities’ into Industrial

Centers with ‘sub’urbs, led to an

expansion of horse ownership for moving

people. The same infrastructure made horse

drawn wagons useful for moving goods and

providing services. (See THE

ESTATES MATRIX 1870 and 1920 time frames.)

The

private horses, plus horses used in public

transit – i.e. the omnibus – and in

goods movement caused the urban horse

population to skyrocket.

Horse

manure piled up in the streets. The European

House Sparrow, introduced to North America to

combat insect larva feeding on Linden Trees

which were a common street tree, learned to

feed year round on the grass and hay seed that

had passed through the horse. As a result, the

House Sparrow population also exploded.

Horse

manure and House Sparrows became the “twin

urban problems” in the Zentra of late 19th

century North American Industrial Centers.

The first automobiles were seen as a

‘nonpolluting alternative to the horse.’

Hopefully,

long before humans have used the Autonomobile

for as long as they have used the horse,

citizens will find that Large, Private

Vehicles, like horses, serves civilization in

much more limited ways than is currently

imagined by Autonomobile manufacturers or most

citizens who do not yet realize there is any

option.

Horse

Power and Horsepower

Climate

change (or is it just a drought?) has caused

pastures in the Piedmont to become more suited

to pigs or goats than horses. The spike in hay

prices has humane societies taking over the

maintenance of neglected horses, even in

“horse country.” This reality has again put

a spotlight on the economic and physical burden

of supporting horses.

Unfortunately

when EMR wrote “The Carriageless Horse,”

Erik Morris had not published “From Horse

Power to Horsepower.” (See End

Note Forty.)

Morris,

a PhD student at UCLA, provides a graphic,

factoid-laden exposition of the use of horse

power in late 19th Century urban agglomerations

and also makes the observation that the

Autonomobile was seen at the time as the

non-polluting “answer” to the horse.

Morris’s

description of piles of horse manure, maltreated

horses and the removal of dead horses could

provide the backgrounder for a horror film. He

paints a gruesome picture of the use and abuse

of horses during the time that horses were used

to provide both private and shared-vehicle

passenger transport as well as for delivery of

goods and services.

Are

Citizens Better Off with the Autonomobile than

the Horse?

There

is no reason to challenge Morris’ images or

data related to the use of horses in Industrial

Centers. There is a very good reason to

challenge his sweeping, sugar-coated

conclusions.

After

describing the chaos caused by the use of horse

power to provide urban Mobility and Access,

Morris teases the reader with a question:

Was

the autonomobile really an improvement given

the current levels of congestion and

pollution?

He

immediately scoffs at the idea that this is even

a rational question, suggesting that it is clear

to any sane person that the current situation is

much “better” than stinking streets full of

horse manure. This is the expected conclusion

because Morris’ work is supported by the

Autonomobile / Business-As-Usual “Complex”

described in PART I.

What

Morris misses (or intentionally avoids) is the

fact that very same root problem existed with

the horse providing Mobility and Access then as

with the Autonomobile providing Mobility and

Access now:

There

was no Balance between the travel demand

generated by the settlement pattern and the

capacity of the transport system. In addition,

there was no governance capacity to facilitate

the creation of this Balance.

The

Morris article documents that the governance

structure was already woefully out of sync with

the economic, social and physical reality of

urban settlement. When applying the new urban-fabric

shaping technology - structural steel framed

buildings, elevators, etc. - the way to make the

most money in the shortest time within the

context provided by Agencies was to build the

biggest possible building on each lot. The

public spaces were not designed to accommodate

horse power.

The

problem was not civil engineering and

construction know-how. Roman roads were built to

withstand the wear and tear of horses’ hooves

and the wheels of carts, wagons and chariots.

The grading and drainage system carried away the

manure and other refuse.

The

problem was not the design of the road system,

it was the design of the street system. When the

Roman roads dumped traffic onto urban streets,

congestion was the result and that was the same

problem in 1870 and is the problem in 2008. (See

End

Note Forty-one.)

In

large urban agglomerations, the Autonomobile and

the internal combustion engine (aka, Large,

Private Vehicles) have not proven to be any

better suited to Mobility and Access needs than

the horse. The reason is simple:

The

lack of balance between the traffic-generation

demand of the settlement pattern and the

capacity of the Mobility and Access system. It

does not matter if the vehicles are chariots

and carts, horse drawn wagons and omnibuses or

trucks and Large, Private Autonomobiles.

The

same problems crop up with Autonomobiles today

as did with horses, only now they are problems

of a Regional scale rather than the scale of

Neighborhood and Village streets. The cumulative

impact of Autonomobiles is worse than that of

the horse but the solutions are the same.

No

one would deny that huddling against a building

and facing the prospect of wading through

knee-deep horse manure was a daunting

possibility. People hoped for a silver bullet.

However, the solution that came down the road

turned out to be no better than the horse.

In

2008, citizens face the same alternative they

did in 1900:

Creating

human settlement patterns that generate

vehicle travel demand which can be served by

the transport system in such a way that there

is a Balance between demand and capacity.

That

means Fundamental Change to create functional

human settlement patterns in Balanced

Communities. It also means Fundamental Change in

government structure to facilitate functional

human settlement patterns.

Before

we get off the horse, there is one more point to

be made. If horses did not solve the urban

Mobility and Access problem and Autonomobiles (aka,

Large, Private Vehicles) only made it worse,

what about small cars? We will explore small,

cheap and sequentially shared cars below but for

now there is a four-legged way to put this

“solution” into perspective:

Visit

Cluster- and Neighborhood-scale urban enclaves

in many parts of the Spanish and Italian

Countryside. Our favorites are the Pueblo Blanco

in the South of Spain. To this day one can find

tiny donkey stables tucked under and between

shops and houses. These little stables take up

less space than would be needed for a horse,

especially a large draft horse. However, a small

stable is still a stable. It still takes up

space and it still smells, especially in the

summer. Every morning the owner loads up a pack

box with donkey manure and hauls it out to a

field.

Lewenz's

Village

There

is another way to get a handle on the fact that

Large, Private Vehicles take up too much space.

Claude Lewenz has recently written a book titled

“How to Build a Village.” (See End

Note Forty-two.)

Jim Bacon has written a review

(see"_____________,") and EMR is

planning to write one, which will appear in

Chapter 17 of BRIDGES. We can say from initially skimming the

book that it contains a number of useful ideas

and insights.

For

the purpose of this Backgrounder we only cite

Lewenz's “definition” of his Village:

“The

Village: A 5,000 to 10,000 population,

self-contained community built around multiple

plazas with cafes, shops, workplaces and artist

guilds and no cars within. With its own local

economy, affordable housing and environmentally

sustainable design, it offers a fulfilling,

wonderful place for all ages and diverse

peoples. Where everything is within a ten-minute

walk.” (See End

Note Forty-three.)

The

Myths

One

other element of the space issue is the focus of

“A

Yard Where Johnny Can Run and Play,” 1

December 2003. This column explores The Big Yard

Myth and documents how the mythology surrounding

the aim of providing a good home for raising

children undermines most of the other needed

resources, including the need to use an

Autonomobile to achieve Mobility and Access.

Myths that perpetuate dysfunctional patterns and

densities of land use will be explored more in

depth in THE USE AND MANAGEMENT OF LAND,

forthcoming.

What

Citizens Value Most

Perhaps

the most important issue to address in any

review of the spacial impact of the Autonomobile

is the misconception that more efficient, non-autocentric

patterns of settlement are characterized by

crowded, rat- infested hovels. People jammed

together against their will. This is another

aspect of the “Manhattan” syndrome noted

above.

Suffice

it to say, as documented in The Shape of the

Future, column after column, when given an

alternative and where there is even a threshold

attempt to make a fair allocation of

location-variable costs, citizens prove in the

market that they prefer non-autocentric

settlement patterns. It is not just singles and

empty nesters that favor these environments.

Even if it were, that covers nearly 75 percent

of the Households in the US of A.

In

spite of what the 12 ½ Percenters would have

one believe, the 87 ½ Percent Rule is based

on hard data that shows that the vast majority have already

chosen to buy, rent and live at the Unit and

Dooryard scales in patterns and at densities

which could be part of functional human settlement

patterns if located in well-designed Clusters,

Neighborhoods and Villages. Same house, same

builder, different location -- studies have

documented this reality for years.

A

Parade of Non-Solutions

In

the following section we review an array of

attempts to avoid reality. These attempts

fail to recognize the need for:

Fundamental

Change to create functional human settlement

patterns in Balanced Communities and

Fundamental Change in government structure to

accomplish the evolution to functional human

settlement patterns.

Zoning.

One response to the settlement pattern

dysfunction that resulted in horse congestion

and then in Autonomobile congestion were

municipal land use controls. The most famous

being “zoning.” Zoning has roots in pre-industrial

revolution regulations and grew in popularity

due to horse congestion. Zoning spread like

wildfire from urban enclave to urban enclave

after being sanctioned by the U.S. Supreme Court

in Ambler Reality vs. The Village of Euclid in

1926.

The

early model zoning ordinance provided a

simplistic non-solution that plagues urban

functions to this day. Zoning excludes some

“noxious” land uses from some parts of the

urban fabric. Not unexpectedly, zoning and the

market created mono-cultures of land uses.

Mono-cultures

in turn generate the demand for far more vehicle

miles of travel. The same is true for scattered

Big Boxes as noted in PART III. It took Jane

Jacobs’ book "Life and Death of Great

American Cities" to popularize the many

downsides of urban fabric monocultures.

If

municipalities intelligently applied the whole

arsenal of “planning” tools including

Official Maps, Capital Programs and

“comprehensive” planning, the results would

have been different. By “comprehensive”

planning we mean “real” comprehensive plans

at the Regional, Community, Village,

Neighborhood and Cluster scales. Such plans

included the concept of Balance. Balance was an

element of the best of these plans as late as

the '60s.

Zoning

is not, in and of itself, a “bad” idea as

some more recent reality based (aka “Form

Based”) code concepts demonstrate. (See “The

Role of Municipal Planning in Creating

Dysfunctional Human Settlement Patterns,”

22 January 2002.)

An

Alternative to Cheap Gasoline. As noted in

PART I, the very first “problem” with

Autonomobiles that occurs to many citizens is

that gasoline is no longer cheap. There is no

rational expectation that gasoline will ever

again be “cheap” unless there are no

Autonomobiles to burn it.

Alternative

fuels are a major topic of debate and fantasy

among those who live by the Large, Private

Vehicle Mobility and Access Myth (aka, Private

Vehicle Mobility Myth).

Alternative

fuels are not a solution for two reasons:

With

dysfunctional settlement patterns and Large,

Private Vehicles, there will be no better

Mobility and Access even if renewable sources

of energy like solar, wind and wave energy can

be delivered at prices comparable to gasoline

in 1973.

The

details to support this reality are beyond the

scope of this Backgrounder, but here are some

landmarks for future exploration:

Without

vast reductions in cost, reliance on new

sources of energy will widen the wealth gap

and thus threaten the existence of democracies

with market economies.

A

good example of why energy will cost a lot is

the potential development of Household-scale

nuclear reactors. (See “Mini

Nuclear Reactors for All,” Bacons

Rebellion blog, 20 December 2007.)

Raising

the topic of nuclear fission or fusion means

both high costs and long-term risks and dangers

unless the release of energy is controlled in

large, expensive facilities and waste programs

made safe in large expensive depositories.

There

is more: The heat must be used near the facility

because heat does not travel well. The same is

true for electricity which is, as noted below,

inefficient to move long distances or to

distribute widely at low voltage.

As

S/P has noted in other contexts:

Renewable

sources of energy – wind, solar, wave,

geothermal and others – are “thin”

(widely distributed) while existing urban

energy demands are “thick” (focused on

less than 5 percent of the land area).

Concentration,

storage, transmission and distribution from

renewable energy is expensive even if the basic

source is “free.” Add to this reality that:

Renewable

sources of energy are location-constrained.

Renewable

energy sources are great for farms, forest

maintenance facilities and other dispersed

activities. Small wind turbines have been used

to generate electricity on farms for a 100

years. Black water barrels have been a feature

on roofs in the tropics for longer. Water wheels

and wind mills to supply mechanical power have

been common for longer yet. (See End

Note Forty-four.)

As

noted above, when the “thin” renewable

sources are converted to electricity they are

very inefficient to transport. The US of A now

wastes half of all energy put into electrical

production in generation, transmission and

distribution to end users.

There

are some who dream of a “hydrogen economy”.

Hydrogen does not occur naturally in a free

state. How much energy from other sources is

required to isolate the hydrogen to replace

gasoline? How much will hydrogen power supplies

cost to produce and deliver? Will they power

Large, Private Vehicles for every one in the

economic food chain or only those at the top?

From

what we already know of the problems with

biomass generation of energy, the hydrogen

options appears to be just a dream. Biomass is

reasonable only if applied to waste. The waste

stream is something that needs to be reduced,

not expanded just to be a source of energy.

In

retrospect, gasoline was a magical elixir.

Everywhere one turns, the alternatives are

expensive or dangerous.

Small

Cars. Another topic that keeps coming up is

smaller, and more energy-efficient Private

Vehicles. We raised this issue in the context of

donkey stables above. There are a range of macro

and micro economic impacts of small cars in both

the First World and the Third (aka,

“Developing”) World.

In

the First World, the GDP impact of shifting to

small Autonomobiles would be traumatic, as

suggested in PART I. In the Third World, selling

every Household a small car would be dramatic as

well. Even a few gallons of gasoline a week

multiplied by billions of uses is a lot of

gasoline, a lot of CO2 and a lot of other

negative byproducts. The big issue, however, is

the disaggregation of human settlement patterns

and the impact of the inevitable, advertising-

driven Small, Private Vehicle myth.

The

prospect of Tata’s Nano, a four-passenger and

one- suitcase vehicle priced at $2,500 brings

these realities into perspective. Richard

Register and others articulate the need to

reconsider the glory of the small car as well as

the Prius and other hybrids. (See End

Note Forty-five.)

The

MainStream Media provides coverage of

alternative size and alternatively fueled

vehicles but to get a clear picture of what

advertising-besotted consumers drool over and

what the Autonomobile manufacturers want them to

buy, check out the programs for 2008 “Auto

Shows” from Paris to San Francisco.

Speed,

power and gadgets along with NASCAR drivers,

sports “personalities” and cheerleaders are

on the front burner at these shows. There is no

difference between the Auto Show hype for

Autonomobiles and the conspicuous consumption

focus of “Boat Shows.”

Tune

in to any athletic event coverage, check out the

Superbowl ads. Big, flashy, sexy. Mobility and

Access is not the focus and neither is

sustainability. What is the bottom line in the

real world?

Beyond

the hype there is some sound analysis to be

accessed via MainStream Media. Where? Why Warren

Brown in the WaPo,

23 March, of course.

We

have cited Brown’s insight in past columns and

Backgrounders. On Sunday 23 March, Brown goes beyond his usual excellence in “Checking

the Extremes at the New York Show.” We have

fond memories of the New York Show in the late

60s where we checked out the then-new MGB-GT,

which we later bought, and then sold, after the

1973 OPEC Oil Embargo.

The

entire column is worth a careful read. We will

come back to Brown regarding Smart Cars but here

is a quote that reflects Brown’s insight:

“It

does not matter what automobile manufacturers

propose, or governments dictate; consumers

will have the final say on what will be done,

how it will be done, and at what pace it will

be done. But the problem, as I have noted in

this space previously, is that consumers are

of varying, often contradictory minds, wanting

to have their oil and burn it too; and wanting

to do it at the cheapest possible price.”

That

is why it is so important for citizens to

receive sound information. (See THE

ESTATES MATRIX.)

Let

us be very clear:

Small

is better, shared is better, small and shared

is better yet.

Any

car, even a “small” car, takes up space.

With vast reductions in size, weight and speed

of vehicles along with a vast increase in the

sharing of vehicles, there could be some

improvement from renewable energy sources and

new technologies. However, the real benefit will

only accrue to citizens if there is also

Fundamental Change in human settlement patterns.

To

maintain anything like the current lifestyles

over the next two or three decades, citizens

would have had to initiate Fundamental Change in

1973. Starting the change in 2008 will be more

dramatic and more painful. If started in 2012

(after the next general election) it may be

impossible.

Smart

Cars in America, Not. Perhaps the best place

to get a grasp of the dynamics of more efficient

vehicles is to tune in on the history of

“Smart Cars.” This history is nearly as

enlightening as a blow-by-blow review of the

demise of interurban trolleys and streetcars

starting a century ago.

Small

cars are common in Europe and have been on the

roads in the Countryside and the streets in the

Urbanside since World War II. This is in

contrast to the US of A, Canada and other

nation-states where almost all Autonomobiles

have grown in size, weight and horsepower. Of

course, a wide array of mopeds, scooters and

motorcycle rickshaws are common in the Third

World, but Europe is the place where the

contrast in size is most dramatic.

Three-wheeled,

two-passengers-and-a-box "scooters” have

been used for farm-to-market travel in Italy and

Spain for years. Some small cars -- Renaults and

VW bugs -- have been sold both in Europe and in

the US of A.

The

post-1973 small vehicle that aimed to provide a ride

that many would consider “safe” is the

“Smart car”. If memory serves, we first saw

what is now termed a “Smart car” on the

streets of Wien in the 80s. As the years went

by, we began to see these vehicles with more

frequency in Europe. We took photographs of a

very sporty model that by this time had a

Mercedes hood emblem in Kobenhavn in the Spring

of 1991. By that time we would have seriously

considered buying such a vehicle, if it were

available in the US of A.

By

2000, Smart cars were common on the streets of

Berlin and other Zentra where two of them were

frequently seen parked nose-to-the-curb with two

in a single parking place. They could also be

seen in smaller urban enclaves and, yes, even on

the Autobahn.

We

have contended for years that there was (and is)

a market in the US of A for Smart cars. Now,

over 20 years after we first thought we might

buy one, Smart cars are now becoming available.

Warren Brown addresses this issue in the column

noted earlier. He allows Anders Sundt Jensen,

the Global Marketing Director, to state the

company line:

“It

would have been impossible to bring that car

here then,” Jensen said. “How could we

possibly have done that? You had the world’s

cheapest gasoline. Trucks and sport-utility

vehicles were 51 percent of your new-vehicle

market. No one in America would have looked at

a Smart car then.”

We

do not buy this excuse for a second. We would

have considered it 20 years ago and so would

others.

Why

so long? The Autonomobile manufacturers,

especially after Mercedes-Benz also bought

Chrysler, make more money producing Large

Vehicles.

Our

neighbor across the back fence put down a

deposit for a Smart Car as soon as he found out

they were available. Months later, last

week, he has finally moved off the waiting list

and has been able to order a specific model and

color. He expects delivery at mid-year. He

introduced us to www.smartcarofamerica.com. Go

to the fora on this site and check for yourself

the number of people who are clamoring for a

Smart Car.

As

the Brown column makes clear, the market is

there. This is a perfect example of where the

current market does not “work” and it does

not work for the reasons Robert Reich lays out

in "Supercapitalism." Citizens would have

benefited 20 years ago from having a Smart car

choice.

Parking

for Recreation, Big Boxes and For Everything

else Too

Now,

with the hard part out of the way, we move to

the easy part of driving a stake through the

heart of the Autonomobile.

There

is one place citizens can enjoy a quantum leap

toward understanding the dysfunction caused by

Autonomobiles. This path to understanding

comes not from an examination of where and how

Autonomobiles are driven but where they are

parked and who pays for parking opportunities.

This

is an area that has been well researched, but

logical actions are, as yet, infrequently

implemented. The field of parking - pun intended

- is far less complex and provides a far easier

to understand illustration of the limitations of

Autonomobiles than even recreation and

entertainment venues or Big Boxes. In addition,

UCLA Professor, Donald Shoup, has laid out the

“problem with parking cars” in clear terms

in op eds, academic research and in books for

general audiences. (For an introduction to the

topic of parking see Jim Bacon’s column “No

Such Thing as a Free Park,” 4 December

2006.)

The

work of Professor Donald Shoup is cited in

Jim Bacon’s column, and those concerned with the

issue of parking will want to follow up with

more reading of Shoup’s work. (See End

Note Forty-six.)

By

applying a commonsense approach to the price of

parking, Shoup has helped eliminate congestion

in a number of contexts. More importantly, when

there is a fair allocation of the cost of

parking, then more incentive exists to find

alternatives to the Autonomobile.

The

bigger issue, however, is that parking takes up

space and disaggregates human settlement

patterns in many places even more than roadways

and streets.

The

data is overwhelming. There are over eight

parking spaces for every Autonomobile. That

means there are over seven million acres or more

of empty parking spaces at any given time

because the car can be in only one of them --

assuming it's not on the roadway.

The

examination of parking is an easy way to grasp

the Large, Private Vehicle problem. The space to

park vehicles disaggregates critical mass

and destroys the ambiance of the places that

visitors seek to access. This is documented in

Part II concerning recreation and entertainment

venues. Good examples are the Main Street

Villages noted in the exploration of

recreational and entertainment venues in PART

II. The same is true for employment, commercial,

retail and residential land uses.

Yet in the face of this reality, retailer after

retailer lobbies municipal official after

municipal official for more parking spaces and

more parking subsidies. An excellent example can

be found in recent action by the Montgomery

County, MD council. (See End

Note Forty-seven.)

Part

V: What

Hath Man Wrought?

The

15th of May 2007, as documented on the front

page of the Business Section of WaPo,

might be thought of in years to come as “The

Ides of May for the Autonomobile Industry.”

There were four major stories on the front page

of the Business section and thee of them dealt

with the future of Autonomobiles.

The

big story was that Daimler Chrysler was selling

off Chrysler to Cerberus Capital Management. The

essence of the Chrysler “sale” was best

captured by the subheading of Alan Sloan’s

“Deals” column: “Daimler Pays to Have

Chrysler Towed Away.”

The

lead story, “Cerberus’ Sharp Tooth Ways:

Firm has History of Turn Around Fueled by

Cuts,” suggested a number of possible future

scenarios for Chrysler. For the auto industry in

general, the sale means the end of the 1948

“Treaty of Detroit” -- labor peace in

exchange for job security. The importance of the

“Treaty of Detroit” is spelled out in

Reich’s "Supercapitalism."

The

third story on the fateful 15th of May is

headlined: “Bush Calls for Cuts in Vehicle

Emissions: Agencies Urged to Draft New Rules.”

At the time, this story was noted as a major

departure from the Bush administrations’s

prior stance with respect to Autonomobiles.

It

turns out that this story foretold a revolution

in Elephant Clan policy. It was the first chink

in six-plus years of stonewalling any link

between Autonomobiles and Energy Security or

Climate Change by the Bush administration. Since

that time, administration policy has started to

reflect the growing Enterprise, Institution and

citizen concern for the role of Autonomobiles in

both Energy Waste and Climate Change. Perhaps it

was only a reflection of the need to create a

credible position in light of the upcoming 2008

elections, but whatever the cause, it was a

fundamental shift. (See End

Note Forty-eight.)

In

future decades observers may look back on the

15th of May 2007 and suggest that in fact this

was the “Tipping Point” that was made

inevitable by the Arab OPEC Oil Embargo of

October 1973.

The

34-year lag in doing something significant about

Autonomobiles and the consumption of imported

natural capital will have a dramatic impact on

the level of pain that is caused by finally

addressing the Mobility and Access Crisis in an

intelligent manner.

The

Blame

The

Autonomobile Era can be bracketed between the

terms of William Howard Taft and George Walker

Bush. Taft and his wife were autonomobile fans

long before Taft was inaugurated. By his

enthusiastic support for Autonomobiles,

including having the government buy

Autonomobiles for his use while President, Taft

became “The First Automobile President.” As

suggested by the Ides of May, George Walker Bush

will hopefully be considered “The Last

Autonomobile President.”

It

may not be fair to tag just these two heads of

state. Had Taft’s predecessor, Theodore

Roosevelt, not been such a bull-headed advocate

of horses there might have been a more rational

identification of useful roles for Autonomobiles.

A

more enlightened use of Autonomobile in the

United States was a possibility because even at

the dawn of the 20th century, citizens and

scholars raised the alarm about potential

negative impacts of Autonomobiles. With a

different federal policy, it may not have taken

98 years to learn what we should have learned

from use of the horse in urban settings as noted

earlier in PART IV.

More

recent administrations also share the blame.

World War I generals lobbied for a better way to

move armor and other heavy military equipment

across the country. They developed the

“Inter-Regional Highways” proposal in the

'20s. The idea came to fruition as the

Interstate Defense Highway program while a former

general, Dwight David Eisenhower, was president.

The booming Autonomobile industry that dominated

the shaping of human settlement patterns in the

'50s, '60s and '70s had far too much political

swat for the nation-state’s future

sustainability.

Many

citizens and their governance practitioners were

deluded by the slogan “What is good for

General Motors is good for America.”

Had

Gerald Randolph Ford, Jr. not feared the results

of further alarming the population following the

Richard Milhous Nixon scandals, he might have

taken far more decisive action -- programs that

reflected the post-Arab OPEC Oil Embargo

reality. Had James Earl Carter, Jr. not

abandoned the 50-cent-gas tax... Had Ronald

Wilson Reagan been more interested in

conservation and less interested in whatever

form of Mass OverConsumption helped

“conservatives” get elected in the short

run... Had George Herbert Walker Bush not been

such good friends with the Saudi’s... Had

William Jefferson Clinton not tried to make

excuses for why the US of A consumed so much

gasoline... (See Chapter 1 of The Shape of

the Future.)

With

any of these recent changes, the US of A could

have started decades earlier to transition

away from Autonomobile dominance. In fact,

every president from Theodore Roosevelt

forward had an opportunity to inspire and

implement a more intelligent Autonomobile

strategy.

The

rational voices of the '20s, '30s, '40s, '50s,

'60s and '70s were drowned out. Some criticized

the decisions to subsidize the demise of

Interurban Trolleys in the '20s and '30s, and

many opposed the subsidized demise of Street

Cars in the '40s and '50s. As pointed out in The

Shape of the Future, Benton Mackaye,

Louis Mumford, Wilfred Owen and others were

marginalized and relegated to working on trail

systems, academic explorations and advising

Third World governments. In the '50s and 60s the

most intelligent voice, that of Will Owen, was

marginalized by his superiors and successors at

the Bookings Institution. (See End

Note Forty-nine.)

All

this is entertaining to speculate about but in

the last analysis, in a democracy with a market

economy, it is citizens who are to blame. Yes,

they were mislead by trillions of dollars in

advertising and fooled by public subsidies for a

strategically unsustainable mobility system.

However, in a democracy the buck stops with

well-informed citizens, otherwise it is not a

real democracy. With glossy ads in Motor Trend

magazine setting the pace, Autonomobiles roll on

to an ignominious conclusion - The Crash.

The

Unsustainable Trajectory

Contemporary

society is headed for The Crash. “Collapse”

is the term used by Jared Diamond in the book of

that title. In the vocabulary of physics “The

Crash” will cause a “Collapse” on an ever

steeper road to entropy.

The

Crash on the road to entropy is what we mean

when we refer to an “unsustainable

trajectory for contemporary civilization.”

No one with an understanding of science, a

grasp of macro-economics or a lick of common

sense can look at the consumption data and not

identify the unsustainable trajectory. (See

End

Note Fifty.)

Some

are blind to the trajectory towards the Crash

that is inevitable if the US of A continues to

rely on Autonomobiles for Access and Mobility.

On 17 April 2007, the Wall Street Journal

published a special section titled “One

Billion Cars.” Jim Bacon summarizes the

material in two Blog posts on 18 April “A

World With One Billion Cars” and “Easing

the Logjam.”

Taken

together, the two Journal stories attempt

to whitewash the prospect of the Crash. The five

ways to ease traffic congestion noted in the

Journal stories are superficial. These

“solutions” (or the more comprehensive list

under the heading The Private Vehicle Mobility

Myth in PART I) would provide nothing beyond a Band-Aid.

They could be helpful tactics on the road to

Fundamental Change but would provide a benefit

only if work is started immediately on a new

trajectory, otherwise they are just feel-good

bromides.

What

If a Different Road Had Been Taken?

There

were warnings a century ago about the impact of

Autonomobiles. Some were just hysterical Ludditisms

but others were well founded. The better

substantiated concerns have been repeated and

confirmed at regular intervals over the past 90

years. It did not have to end in The Crash.

Think

of where citizens would be if only the

leadership of the US of A had paid attention to

the clear warning of October 1973.

Unfortunately, at no time has there been the

political will to make Fundamental Changes

needed for the unsustainable trajectory to be

abandoned and the current condition turn out

differently.

Some

citizens, including the author, took decisive

individual and small group actions. From time

to time, some take such actions to this day.

These actions are not, however, backed by

Agency, Institution and Enterprise initiatives

of meaningful magnitude. Since October 1973,

there has never been a critical mass of citizens

willing to change enough to make a difference

with respect to Autonomobiles.

What

happens when there is no feedstock for

gasoline?

(See

End

Note Fifty-one.)

Where

is the energy going to come from to isolate

hydrogen gas for fuel cells?

The

existing Big Grid electrical energy system

wastes as much energy in generation,

transmission and distribution as is delivered

to the end user.

What sense does it make to dump

more natural and financial capital into a

leaking system?

As

noted above, beyond the issue of fuel

availability and cost, no new fuel will solve

the problem of Large, Private vehicles. That is

a matter of physics not policy or politics.

What

happens to Households, Enterprises, Institutions

and Agencies that rely on auto-exclusive

development patterns when the percentage of

adult citizens who cannot afford to drive a

Large, Private vehicle grows from 20 percent to

80 percent?

What

happens when the cost of Large, Private Vehicles

reaches the point that only the rich can afford

Mobility and Access? There is reason to believe

it will foretell the end of democracies and

market economies.

One

thing left off the list of the Problem with Cars

in PART I was an indirect cost:

The

cost of traffic accidents beyond the fatality

toll.

See

“The

Truthful Cost of Traffic Accidents,” 5

March 2008.

Perhaps

the most compelling problem on the horizon is

that there is no alternative mode of

transportation to support dysfunctional

scatteration of human settlement that has been

generated by, and now requires the extensive use

of, Autonomobiles to achieve Mobility and

Access. (See the description of the Sao Paulo

New Urban Region in “The

Whale on the Beach,” 28 August 2006) and

the false hope of being able to fly in “The

Skycar Myth,” 15 November 2004.

Had

things been different, citizens would now

consider it logical to acquire an interest in a

small, recycled low energy-consuming vehicle

every 15 years instead buying a Large, Private

Autonomobile every one, two or three years. With

these vehicles, the settlement patterns would

have evolved to reduce travel demand.

Most

important, the US of A would have the moral high

ground and be able to lead international efforts

to achieve a sustainable future trajectory for

civilization. The US of A has wasted decades in

denial. For over a decade, the elected

leadership US of A has rejected and attempted

the discredit the concerns expressed at Kyoto.

Now the “leadership” is supportive of “voluntary” actions. As Reich points out in

"Supercapitalism," voluntary restricts are an

exercise in futility.

Instead

of setting an example, the US of A is a laughing

stock of First World nation-states and has no

grounds for criticizing China or India about

grossly expanding per capita energy consumption

and equating the rise of Autonomobile ownership

with “progress.”

Strategies

that Start Citizens in the Right Direction

In

PART III-Learning from Big Boxes, several

immediate steps to curtail Big Box-related

Autonomobility were noted. In this section,

other ideas to move beyond Autonomobility are

summarized.

A

comprehensive survey of the six overarching

strategies necessary to implement Fundamental

Change in human settlement patterns and

Fundamental Change in governance structure are

presented in Part IV (Chapters 23 through 30) of

The Shape of the Future. The

following are highlights related to transport,

Mobility and Access.

Chapter

23 deals with Sustainability. Use of

Autonomobiles to provide Mobility and Access is

not sustainable based on the criteria explored

in this chapter.

Chapter

24 documents that the first step toward

achieving a sustainable trajectory for

civilization is for Agencies, Enterprises and

Institutions to create citizen (individuals and

Households) understanding of the need to fairly

allocate the full location variable costs of

goods and services. As suggested in THE ESTATES

MATRIX, S/P suggests that it is up to citizens

to evolve an information gathering and

dissemination function in the Fourth Estate.

Agencies, Enterprises and Institutions will not

do this.

Autonomobiles

and the Large, Private Vehicle System (L,PVS)

are prime targets for education and immediate

action. The current direct cost of moving an

Autonomobile from point A to point B is NOT

the cost of relying on Autonomobiles for

Mobility and Access.

There

are also indirect costs of the A-to-B trip that

are not yet even recognized. These include the

impact on air and water quality and the

overarching impact on Climate Change, land

misuse, etc. These are costs of current

strategies to rely on Autonomobiles for Mobility

and Access.

Next

there are the costs of maintaining the roadway

system. The reason there are multi-billion

dollar infrastructure shortfalls in every New

Urban Region, including bridges that fail, is

that the current system is not paying the total

direct cost. (See End

Note Fifty-two.)

Next

there is the cost of parking which is said to be

96 percent subsidized by non-vehicle use related

payments. OK, even if the number is only 90

percent... Fair allocation of the cost of

parking would yield a more efficient use of

parking, but more importantly, it would put a

spotlight on the failure of the Autonomobile as

a mode of transport to achieve Mobility and

Access.

The

big ticket item, however, is that the space

required to drive Autonomobiles and park them

when in use disaggregates human settlement

patterns, and thus all human activity, in such

profound ways that the cost of almost every good and service

is impacted.

If

the costs were fairly allocated far fewer

would drive Large, Private Vehicles and shared

vehicle systems would be a much more highly

appreciated bargain.

Chapter

25 suggests that Agencies, Enterprises and

Institutions embrace new Mobility and Access

strategies based on the realization that

Autonomobiles (and trucks) are inefficient

vehicles to overcome space and distance. In

fact, as we have outlined in this Backgrounder,

Autonomobiles disaggregate urban settlement,

which generates economic, social and physical

dysfunction. A comprehensive Mobility and Access

strategy requires the evolution of:

While

longer-term and more Fundamental Changes are

made in the allocation of location-variable

costs and creation of new Mobility and Access

systems, there are immediate steps to take to

start to level the playing field:

Chapters

26, 27 and 28 explore strategies beyond

transport policies and programs. There are many

other actions that would impact settlement

patterns and make them more supportive of

shared-vehicle systems. The most important one

is a tax on land instead of improvement to

discourage speculation and encourage the full

use of existing public services. (Hello again,

Henry George!)

Chapter

29 documents that to achieve a full, fair

allocation of the location-variable costs,

including Autonomobiles, there must be a

Fundamental Change in nation-state, Regional and

Community governance structures.

Portal

to Portal Wages

Here

is something to chew on that you may have heard

about half a century ago but has not been

seriously thought of since.

Before,

during and just after World War II, labor unions

representing coal miners sought “portal to

portal” wages. The problem was that after the

miner entered front gate of the mine property,

they waited for a vehicle to take them deep into

the mine. The miner’s pay did not start until

they reached the mine face - the place they

started loading coal onto the mine cars. The unions

argued that pay should start when the miner got

to the mine property (the portal) because the

mining company was in control of the speed with

which they got to the place where they went to

work.

Now

there are Agencies handing out subsidies for

Enterprises to create jobs: for instance,

warehouses for Big Boxes noted in PART III.

These are not new jobs in Balanced Communities,

they are jobs in remote and scattered locations.

Almost without exception, the new job holders

have to drive long distances to work.

Why

not institute a modest program that requires any

Enterprise receiving a job-creating subsidy to

be take an interest in where the workers live.

Under such a program, the Enterprise would pay

the workers for any travel time beyond the first

and last 10 minutes of their journey to and from

work. After five years, if there is Affordable

and Accessible Housing in close proximity to the

job, the employee holding that position does not

collect “New Portal to Portal Wages.”

This

program would put any subsidy applicant on

notice that creating new jobs far from the

resources needed to support a labor pool is not

a good idea. More importantly, it will cause

everyone involved to consider the need for a

jobs/housing Balance, the first step in creating

a J / H / S / R / A Balance needed to create

Balanced Communities. This type of

new policy requires Fundamental Change in

governance structure - that is also a good

thing. Creative thinking would turn up other

contexts to introduce New Portal-to-Portal pay

or other ways to level the playing field.

A

Modest Prediction

More

than the atomic bomb, poison gas, drug resistant

disease, pharmaceuticals in the water supply,

genetic engineering of plants and animals or

nanotechnology gone bad, over population, Mass

OverConsumption and Autonomobile driven

dysfunctional settlement patterns will be seen

as the primary instruments of destruction of

21st Century First World Civilization.

The

Autonomobile is the tool that has provided for

the mechanized disaggregation of human

civilization.

The irony is that Agencies and

Enterprises have required almost every Household

to acquire the instrument that distributes,

deconstructs and disaggregates society.

Transport is the canary in the minefield of

dysfunctional human settlement patterns.

Autonomobility

is the canary in the minefield of human

civilization unsustainability.

PART

VI

Postscript

In

this Backgrounder, we have noted genetic

proclivities of humans that favor Large, Private

Vehicles that underlie the Private Vehicle

Mobility Myth. We have also noted genetic

proclivities that drive the market for Big

Boxes. The current governance structure has

demonstrated a lack of political will to make

changes necessary to address the forces driving

unsustainable trajectory of contemporary

civilization.

As

we were completing the editing of “The Problem

With Cars” it occurred to us that it is

altogether possible that the genetic

proclivities of humans which have driven them to

achieve the current status of society are not

capable of carrying humans further and thus have

put civilization on an unsustainable trajectory.

This is not a completely new insight.

We address this issue in Chapter 10 Box 4,

"The Evolution of Brain Power," and in

Chapter 23 of The Shape of the Future,

which examines the issues of sustainability.

In

"Collapse," Jared Diamond suggests

there are two overarching prerequisites avoiding

a catastrophic end to a society:

Perhaps

the ability to reconsider genetic proclivities

is a key element of the second criteria. (See End

Note Fifty-three.)

Beyond

strategies that focus on evolution of functional

patterns and density of land use there must

evolve an ethic of community responsibility and

sharing at all scales. Citizens must learn to

temper proclivities to acquire goods and enjoy

them in private with complementary proclivities

that support Alpha components of human

settlement patterns, including Communities and

New Urban Regions. These might be termed

actions to establish a Balanced between

individual rights and community

responsibilities. You may have heard of that

element of Balance from the Communitarians.

The

Autonomobile and the settlement patterns driven

by the Autonomobile reinforce the opposite

result. It is time to right the Balance.

--

April 7, 2008

End

Notes

(39).

In the column “Regional

Rigor Mortis,” 6 June 2005 (and in several

subsequent columns) we suggest that Sao Paulo,

Brazil, provides a powerful

three-dimensional portrait of future immobility

and isolation unless there is Fundamental Change

in human settlement patterns and Fundamental

Changes in governance structures.

(40).

Morris, Erik,; “From Horse Power to

Horsepower,” Spring 2007, Access, the

quarterly magazine of the University of

California Transportation Center.

(41).

There are interesting examples of places

where streets were designed for horses. Streets

in Santa Maria, Calif., which was laid out as an

agricultural service center, were designed to be

wide enough so that two bean wagons pulled by a

6-horse team could make a U-turn in the middle

of any block. The streets in Salt Lake City were

also designed for easy maneuverability of

horse-drawn vehicles.

(42).

Lewenz, Claude. “How to Build a Village,”

Village Forum Press, Auckland, New Zealand.

(43).

Lewenz’s Village could be an Alpha Village

and there are many potential places within New

Urban Regions and Urban Support Regions for such

a Village to exist.

(44).

Think how great it would have been if the

Rural Electrification Administration (REA) had

developed small, self-installed and

self-maintained generation facilities for farms

instead of a long, low voltage distribution

systems that wasted billions of kilowatt hours

in generation, transmission and distribution.

This waste of energy and the subsized

“rural” telephone service was, and is, a

prime driver of the scatteration of urban

dwellings across the Countryside. At least, as

of March 2008, REA is no longer getting low cost

loans to build coal-fired generating plants to

produce electricity for sale to urban consumers.

(45).

For a review of Nano’s impact, see

“World’s Cheapest Car Goes on Show Tata

Motors Has Unveiled, ” www.BBC.co.uk 10

January 2008; Kamdar, Mira, “The Peoples Car:

It Costs Just $2,500. It’s Cute as a Bug. And

It Could Mean Global Disaster,” Wapo 13

January 2008; Applebaum, Anne. “Tiny Car,

Tough Questions,” Wapo 15 January 2008.

Richard Register posts his views of hybrid cars

and related topics at www.ecocitybuilders.com.

(46).

Professor Shoup provides an easy-to-understand

profile of one aspect of the parking issue in

“Gone Parking,” an op ed in the 29 March

2007 issue of the New York Times.

Shoup’s signature book is “The High Cost of

Free Parking.” In this book he argues that the

capital value of parking ($2.5-trillion) exceeds

the value of vehicles ($1.1-trillion) and of

roadways ($1.4 trillion) in the US of A. This

observation substantiates the reason Big Boxes

seek cheap sites as noted in PART III.

(47).

WaPo “Council repeals Parking Increase:

Broad Criticism Stuns Montgomery,” by Mariana

Minaya, 1 August 2007.

(48).

The September 2007 “Climate Change Summit”

turned out to be a toothless volunteer exercise

in futility but it acknowledges that the

majority of the citizens now believe that

Climate Change is real and that humans are

contributing to this world wide change.

(49).

Add to this list Kenneth Schneider, who in

1971, two years before the OPEC Oil Embargo,

published “Autokind vs. Mankind: An Analysis

of Tyranny, A Proposal for Rebellion and A Plan

for Reconstruction.” This book, called to our

attention by Richard Register, supplements the

volumes cited in End Note Five.

(50).

Among the data that needs to be examined in

this context:

Some

of the current trends can be turned around in

the short term, but most are driven by and will

be changed only by Fundamental Change in human

settlement patterns as documented in The

Shape of the Future.

(51).

Every alternative fuel that has been

suggested has a major downside: Corn requires

more energy to grow, distill and transport than

is produced by the ethanol to which it is

converted. Converting corn to ethanol is already

raising the cost of basic food products. Land

for raising sugar cane to produce ethanol in

Brazil clears existing forest which now acts as

a sink for carbon. This reality plus

inefficiencies of production and transport

results in more energy being consumed than saved

by burning sugar-based ethanol.

(52).

The Victoria Transport Policy Institute has

data on this and other currently unmet costs.

(53).

Jane Jacobs died between the time Jared Diamond

wrote "Guns, Germs and Steel" and the

time he wrote "Collapse." Before she

died, Jacobs wrote "Dark Age Ahead,"

published in 2004, in which she sketched out out

what she “thinks” Diamond might conclude if

he were to write a book on the topic of

"Collapse." She highlighted the need

for a human society to maintain creative vigor

if it is to avoid a “dark age.” The topic of

proclivities will be important to explore in the

future.

|