|

You

start to understand how seriously Northern

Virginians take their commuting when you step

into one of the three Commuter Stores in Arlington

County. Set in typical retail locations -- the

Crystal City store is located directly across from

the Hamburger Hamlet -- these shops are jam-packed

with information about different ways to get around

Arlington and the rest of the metro area.

Want

Metro rail schedules? Got 'em. Want bus schedules

for every bus system in the region? Got 'em. Want

info about car-sharing services like ZipCar and

FlexCar? Got it. If you're a technophile, you soak

up information through PCs, digitized maps or watch video

commercials displayed on big-screen TVs. If you

crave human interaction, a store clerk can walk you

through the choices.

The

three stores, located in Rosslyn, Ballston and

Crystal City, generate about 250,000 visitors per

year -- in a jurisdiction of 200,000. Remarkably, 40

percent of the patrons don't even live or work in

Arlington. They come because the stores make it so

easy to find the information they're looking for.

The stores also sell about $7 million in rail and

bus tickets annually.

Arlington

County doesn't operate the stores for profit -- it

provides them as a service. The goal, explains Chris

Hamilton, commuter services chief for the county, is

to provide the information that people need to get

out of their cars. "My group's mission is all

about providing accurate and timely information and

service to make it easy for people to use options

like transit, biking and walking. We try to get

people to change their behavior."

The

Commuter Store in Crystal City

The

Commuter store is just one of the tools Arlington

County uses to combat traffic congestion. Arlington

is the leading jurisdiction in Virginia -- and a

pace-setter nationally -- in creating innovative

alternatives to the auto-centric society. It has

come as close as anyone to finding the formula for

reconciling population growth, commercial

development and quality of life.

In

contrast to most urban-core jurisdictions,

Arlington's population is growing -- faster than one

percent per year since 2000. What's more, Arlington

is growing up, not out, which means that population

density is increasing. At 7,700 inhabitants per

square mile, Arlington's density is exceeded in

Virginia only by Alexandria's. It is three times

that of neighboring Fairfax County.

Remarkably,

new development is concentrated overwhelmingly in

the 11 percent of the land that is zoned commercial.

Since 1970, the square footage of office space in

the Ballston-Rosslyn corridor has increased from 5.5

million square feet to 20.5 million, the number of

jobs from 22,000 to 90,000 and the number of

residential units from 7,000 to 26,200. Developer

proposals for that kind of focused,

high-density growth are normally met with fear and

loathing across Virginia.

In the public mind, density = congestion. But, as

Arlington has irrefutably demonstrated, density need

not creation congestion at all.

The

proof is in the numbers. While secondary roads

across Virginia are clogging up with more traffic,

several Arlington thoroughfares have seen less

traffic over the past 10 years. Most show modest

growth, averaging around 1/2 percent per year. Admittedly, some

major traffic corridors like Interstate 66 are

overloaded, but they facilitate regional traffic

flows for the most part and are funded, designed and

maintained by the Virginia Department of

Transportation.

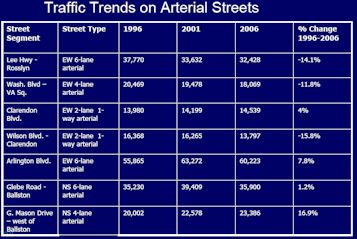

This

table from an Arlington County PowerPoint

presentation shows how traffic has declined or

stabilized in selected arterial streets over the past 10 years.

To

understand how Arlington has vanquished the density

demon, it is necessary to look at three distinct but

interrelated sets of policies: (1) Creating

transportation options, (2) enforcing appropriate

land use policies, and (3) marketing the one-car

lifestyle to citizens.

Arlington

enjoys a significant asset that few Virginia

localities can match: ten stations in the Washington

Metro heavy rail system. Five reside in the

oft-celebrated Ballston-Rosslyn corridor, and five

are located in a line that runs from Washington

National Airport, past the Pentagon, to Arlington

Cemetery.

Some

may argue that the existence of the subway makes

Arlington useless as a model for other

jurisdictions. But remember three things. First, heavy

rail is not a panacea. The presence of Metro has

made little difference to congestion in neighboring

Fairfax County. Second, other communities are

contemplating Transit Oriented Development: notably,

in Norfolk and along the Virginia Railway Express in

Northern Virginia. Third, as Paul Ferguson, chairman

of the Arlington County Board of Supervisors, points

out, it's entirely possible to

promote "smart growth" in neighborhoods

served by bus, not rail, as evidenced by what Arlington

has done in the Shirlington Town Center. (See "Libraries

as Liberators" for a discussion of

re-development in Shirlington.)

As

an integral player in the Metropolitan Washington

Area Transit Authority, Arlington enjoys the benefit

of regional bus service as well as heavy rail. Plus,

the county has upped its commitment to bus transit,

operating its own system of smaller, feeder buses.

Serving routes that Metro doesn't, the ART

(Arlington Transit) buses -- they're big vans,

really -- funnel passengers to Metro stations and to

stops on Metro bus routes.

Arlington

also has invested in bicycle infrastructure: 36

miles of multi-use, off-street trails and 50 miles

of on-street connecting bicycle routes. The county

goal is to build a 111-mile system within 20 years.

To encourage cycling, the county requires developers

to include bike racks in their projects and, in new

projects, to

equip office buildings with shower facilities where

cyclists can change from their biking clothes into

their work clothes.

But

simply providing the rail service, buses routes and

biking amenities will not get people to use them. Transportation

facilities must be integrated with each other, and

with the urban fabric. As Bob Brosnan,

director of the county planning department, puts it,

"We wanted a transportation system, not just a

commuter rail line running through our

community."

Density

around the Metro stations is key. People are

generally willing to walk a quarter mile to catch

the Metro. That means filling the space around the

Metro stations with buildings, not parking lots.

Arlington has encouraged "pyramid" style

development around its Metro stations, in which the

tallest buildings are clustered around the station,

and buildings drop in height the nearer they get to

surrounding neighborhoods of single-family

houses.

Arlington

County encourages mixed uses: office buildings apartment/condominium buildings,

with restaurants,

shops and services accessible in street-level

store-fronts. Adding 19,600 housing units since

1980, the Ballston- Rosslyn corridor accounts for

most of the county's residential growth.

Planners and developers work hand-in-glove to create streetscapes where

people feel comfortable walking, sitting and

congregating. The five Metro station areas in the

Ballston-Rosslyn corridor are adorned with wide

sidewalks, shade trees, mini-plazas and pocket

parks. Corridor streets are narrow, with no more than four

lanes of moving traffic, and speed limits are low --

crossing the street on foot is a normal experience,

not an intimidating one. Although the county

provides limited on-street parking, there are very

few parking lots -- most parking is located

underneath the buildings.

The result is a string of

urban islands where people can reach many of their

destinations -- including the Metro -- on foot.

According to Arlington County statistics, 10 percent

of the people living in the Ballston-Rosslyn

corridor walk to work. The number for the county as

a whole is six percent -- about six times the

national average. (The bicycling program, by

contrast, has yet to make a serious dent. The

percentage of Arlington workers biking to work is

about one percent, in line with national

averages.)

Infrastructure

and land use are critical, but there's one more

essential step: marketing. Americans are so

accustomed to relying on their automobiles, they

need some hand-holding to learn how to use the

subway and bus. That's where Chris Hamilton's

commuter services come in. Arlington County

aggressively markets the transit alternatives.

Besides supporting the three

commuter stores, Arlington maintains an elaborate website,

a call center and an outreach program with major

employers.

The

employer outreach program is particularly effective.

The county's Arlington Transportation Partners

program encompasses 600 companies, representing

about 125,000 employees or two-thirds of the

workforce. The county works with the companies to

set up programs to encourage Metro ridership and

telework. "There are all

kinds of business reasons why an employer should

care about an employee's commute," says

Hamilton. Employee productivity and health are

foremost among them

Recently,

the county has designed three different types of

kiosks that employers can install in their

buildings: stand-alones, desktop models and

wall-mounted models. Employers can pick the one that

works the best. Displays provide a map of Arlington,

a map of the immediate vicinity and schedules of

local routes. Commuters can pick up fliers, which

the county keeps scrupulously stocked, or access

more information on the Internet.

A

common thread of Arlington's outreach program is

promoting the one-car lifestyle: Save money by

driving less. With the average cost of automobile

ownership accounting for 17 percent of household

expenditures in 2001, the county pitches,

Arlingtonians can stretch their paychecks by getting

rid of a car.

County

numbers show that households in the Ballston-

Rosslyn corridor own 1.13 vehicles on average,

versus 1.53 in the rest of the county. Thirty-eight

percent of Ballston-Rosslyn corridor residents used

public transit to get to work, according to 2000

Census statistics, compared to 10.4 percent in the

"inner suburbs." As noted previously, 10

percent walk to work.

In

another indicator that the Arlington model reduces

the number of automobile trips, Metro ridership

continues to surge, decades after the rail system

was built, as new development adds offices, apartments and condos

within walking distance of Metro stations. The

chart below shows the gains at four of the five

stations in the Ballston-Rosslyn corridor. In total,

the increase in Metro ridership

eliminates more than

45,000 automobile trips each day.

|

|

|

Average

Daily Ridership

|

|

|

1991

|

2006

|

|

Rosslyn

|

13,637

|

31,662

|

|

Court

House

|

5,561

|

14,199

|

|

Clarendon

|

2,964

|

8,190

|

|

Ballston

|

9,482

|

24,150

|

|

Total

|

31,644

|

78,201

|

|

|

Arlington's

one-car lifestyle isn't for everyone, but its appeal

is growing. In his book, "How to Live Well Without

Owning a Car," author Chris Bailish contends

that Americans can save $25,000 to $30,000 over a

five-year period by dispensing with just one car. And that doesn't

include the health advantages of walking/cycling

more or the environmental benefits of burning less

gasoline. The county was so taken by Bailish'

message that it partnered with him to re-publish the

book with a chapter devoted to car-free living in

Arlington County.

The

message seems to be sinking in as Arlingtonians

discover that they truly can live with a single car.

(See "Loving

the One-Car Lifestyle," in the Bacon's

Rebellion blog.) A measure of the growing trend

is the growing market for Zipcar and Flexcar,

companies that provide hourly car rental services

for those occasions when subscribers just absolutely

have to have a car. Between them, the two companies

have nearly 4,000 customers in Arlington, says

Hamilton. The county provides on-street parking

where the cars are parked between jaunts. Demand has

gotten so strong that the county is planning to double the number of

car-sharing slots on the streets.

It

should be clear to any open-minded observer that Arlington

County has tackled the traffic congestion problem

more successfully than anyone else in Northern

Virginia. If you don't find the traffic statistics

convincing, take the

trouble, as I did, to spend a day -- including rush

hour -- driving and walking around the Ballston-Rosslyn

corridor.

The

big question is this: How much does it all cost?

Heavy rail, buses and commuter stores don't come

free. If Arlington County is subsidizing alternative

transportation, how much comes out of the pockets of

county taxpayers?

According

to Arlington Communications Director Diana Sun, the

major expenses can be summarized as follows:

|

Local

Tax Support for

Alternate

Transportation

|

|

(in

thousands of dollars)

|

|

|

FY

2006

|

FY

2007

|

FY

2008

|

|

Metro

Rail and Bus

|

13,000

|

14,700

|

17,400

|

|

Local

Bus (ART)

|

7,331

|

6,382

|

6,614

|

|

Commuter

Services

|

538

|

186

|

186

|

|

Total

|

20,869

|

21,268

|

24,200

|

It's

important to note that those numbers may understate

the total subsidy for alternate transportation. They

don't include state or federal contributions to the

programs, or miscellaneous items such as the in-kind

value of providing free parking spaces to Zipcar and

Flexcar. But it provides a reasonably fair account of what

Arlington taxpayers are paying.

The

expenditures for Fiscal 2008 work out to about $120

per Arlington County resident. If you're a

dual-income family that can dispense with one of its

two automobiles costing $5,000 a year, the $240 you

pay in taxes represents one

heck of a positive cost-benefit ratio, even after

deducting for the cost of Metro fares and

car-sharing rentals. If you're a

family of four living in a traditional two-story

house on a traditional tree-lined street, the

payback on your $480 tax contribution isn't so

direct. But the benefits are tangible nonetheless:

Streets are less congested than in neighboring

jurisdictions.

If

$120 per capita still sounds like a lot of money,

compare it to the roughly $200

per resident per year that Northern Virginians will begin taxing

themselves, under newly enacted legislation, to fund

road and highway improvements. Even proponents

concede that the spending program will only blunt

the inevitable increase in congestion, not reduce

it.

The

important lesson that Arlington teaches is this:

Density need not create congestion.

Poorly conceived re-development projects may well

create problems, but transforming low-density

"suburban" districts into Arlington-style

"urban" districts can help alleviate

gridlock. Rather than block high-density development on the grounds that it

will aggravate traffic congestion, as many

neighborhood groups do,

citizens should focus on making sure the development

is done right. They need go no farther than

Arlington County to see how.

--

August 13, 2007

|