|

It

is time for everyone to get on board the train

for Dulles. By this we mean:

Unless

all the stakeholders who want to see METRO

extended to the Centre of Greater Tysons

Corner and on to Dulles International Airport

get on the same train very soon, there will be

there will be no METRO extension to Dulles.

(See End

Note One.)

There

may be future options to connect the Centroid of

the National Capital Subregion with Dulles

International Airport via a shared-vehicle

system, but not with a METRO extension. Further,

we predict that any new system – a sketch

outline of such a system can be found in “Rail-to-Dulles

Realities” (Jan. 5, 2004) – will be a

long, long time in coming.

Those

who follow The Shape of the Future

columns may jump to the conclusion we have

written all we could about “Rail To Dulles.”

(See End

Note Two.) That is not the case. In the

light of recent events and further analysis,

this column rearticulates, expands and amends

what we wrote about METRO to Dulles in September

2006 (“Two

Steps Backward”) and in recent posts on

the Bacon's Rebellion Blog.

The

Headlines

The

30 March Dulles Transit Partners, LLC, press

release and the 31 March WaPo coverage

seems to close the door on a tunnel for a METRO

line through Greater Tysons Corner. (See “Contract

Set for Rail Line To Dulles: Prospects Look

Dim For Plan to Tunnel Beneath Tysons Corner”

by Bill Turque, and End

Note Three.)

The

new contract may not end the tunnel vs

overhead debate. However, further arguments

over tunnel vs overhead will compound the

already substantial hurdles to be overcome if

there is to be METRO compatible

Rail-to-Dulles in our lifetimes.

This

was the message of Doug Koelemay’s column in

the 21 March edition of Bacons Rebellion (“Tunnel

Vision”). Koelemay expressed well the

“do not let the perfect chase out the good”

argument that is a mantra of Business As Usual.

In this case, Koelemay is probably right. There

are so many other barriers that a prolonged

tunnel vs overhead conflict may kill the project

as now envisioned. METRO is a 50-year-old

technology, and few citizens favor the high-density

settlement pattern that METRO-like systems best

support.

There

is another important reality:

If

METRO through the Centre of Greater Tysons

Corner consists of an elevated track that in

any way resembles the graphics that the WaPo

has published, it will be the kiss of death

for any evolution of Greater Tysons Corner

into a functional, urbane, much less Balanced,

Community.

If

the “photo simulation” of the proposed rail

is representative of what is actually built,

there is no way to put lipstick on this pig. The

overhead photo simulation is not merely ugly: A

METRO line on stilts in a roadway median will

not provide mobility and access for Greater

Tysons Corner. This configuration will leave the

Autonomobile as the preferred way to get to,

from and around-in the Centre of Tysons Corner.

Roger Lewis articulates this view well in “Why

Going Underground Makes Sense in Tysons

Corner” in the 17 February 2007 WaPo.

Upon

Further Review

Back

in September we castigated Governor Kaine for

withdrawing his support for tunneling under all

of Tysons Corner (“Two

Steps Backward,” 17 September 2006).

Conventional wisdom holds that the only

civilized way to locate a high-capacity,

shared-vehicle system in an urbanized area is to

put it underground. Many also argue that

tunneling is the only strategy that makes

economic sense in the long-term. Based on past

experience, elevated lines are often equated

with blight. See the Roger Lewis column cited

above.

This

preference for underground Metro is based, in

large part, on the fact that almost all good

examples of high-capacity,

shared-vehicle-system-served urban fabric have

the transport system underground. The

Underground (aka, Tube) in London, Metro in

Paris, U-Bahn in Berlin, Tunnelbanan in

Stockholm, Subway in Toronto, BART in San

Francisco, MARTA in Atlanta – almost every

high-capacity system in the First World (except

Miami) runs primarily in tunnels within the

Centre (aka, “downtown”). Closer to home,

tunnel advocates point to the Centre of the

Federal District and to the Rosslyn-Ballston

Corridor.

Upon

further review the absolute necessity for a

tunnel is not as clear cut as I suggested it was

in September:

-

In

all of the examples cited above, the pattern

of land ownership (and buildings) as well as

the streets and roadways to serve urban land

uses were in place before the shared-vehicle

system was installed under the already-urban

streetscapes. For reasons we will explore in

some detail below, this is a critical issue.

This condition is unrelated to the broad

arterial rights-of-way that the METRO line

extension is planned to follow through

Greater Tysons Corner.

-

In

the “Two Steps Backward” column we

spelled out several possible silver linings

from the Kaine decision. One was the

potential to abandon all efforts to “save

Tysons Corner” and to shift the focus of

urban activities in the Radius = 5 Miles to

Radius = 25 Miles Radius Band from Greater

Tysons Corner to Greater Reston, Greater

Fairfax Center, Greater Springfield, etc.

This “silver lining” assumes that there

will be the public and private resources

necessary to cover the cost of abandonment

and rebuilding elsewhere the urban fabric

capacity that is now present in the Centre

of the largest Beta Community in the

Virginia portion of the National Capital

Subregion. That well-spring of resources may

not exist in the future.

-

Finally,

and most importantly, the National Capital

Subregion is facing a major Mobility and

Access Crisis (as well as an Accessible and

Affordable Housing Crisis and a

Disaggregation of Settlement Pattern Crisis)

that is already impacting every citizen of

the Subregion and of the Washington-

Baltimore New Urban Region.

As

we have been arguing since 1982 and have been

writing for the last 20 years, METRO is the only

mobility and access system that has excess

capacity. Most METRO trains still leave most of

the METRO stations most of the time essentially

empty. (See “It

Is Time to Fundamentally Rethink METRO.”)

A

key to solving the crises facing the National

Capital Subregion is to rationally use METRO

station areas and the METRO system capacity.

Intelligent design, and implementation of METRO

in creating Rail-to-Dulles and Rail-to-Tysons

Corner, could be an important first step.

The

next Rail-to-Dulles milestone is May, when the

Federal Transit Administration is scheduled to

conclude a “risk assessment.” The biggest

“risk” is that someone in the administration

will see federal money spent for Rail-to-Dulles

as a threat to some other administration

program. The more parties that are on the same

train, the less likely any individual obstacle

will kill the prospect of Rail-to-Dulles for the

foreseeable future.

We

also have a personal reason to look for a basis

for consensus. We have traveled to Cleveland,

Chicago and Atlanta to ride the shared-vehicle

system to the airport. We have gone out of our

way to do the same in Paris, Roma, Munchen and

London. We hope to do the same in Dulles, having

been professionally involved in Rail to Dulles

since the early 80s.

Some

will recall that we suggested repeatedly, from

the mid 80s onward, selling the National Airport

site and using the funds to extend METRO to

Dulles Airport. Given the...

-

current

expansion of Dulles capacity

-

flat

air travel demand since 11 September 2001

-

growing

concern for noise generated by flights to

and from National Airport, and

-

many

good economic and ecological reasons that

air travel numbers should not grow

...the

sale of the National site might have been a very

good idea.

The

“Sale of National” idea’s time may come

again. Think how much better it would have been

to have the Air and Space Annex at a METRO stop

and a historic airport. But that is another

story.

Broad-Based

Support

Right

now it is hard to find anyone who thinks it is

not a good idea to extend METRO to Tysons

Corner. Support for extending METRO to Dulles

via Greater Reston is almost as strong. That has

not always been the case. (See End

Note Four.)

Right

now it is hard to find anyone, except a few who

live very close a specific rail station, who

does not think it is a good idea to put

intensive development in METRO station-areas. In

March, the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors

adopted a new policy on this issue. The 13 March

2007 WaPo article, “Dense

Development Sought Near Transit: Fairfax

County Policy Will Promote Pedestrian-Friendly

Areas Near Stations,” by Amy Gardner and Bill

Turque is a generally factual report of what

went on when the Board of Supervisors adopted

new, and very intelligent, .25- and .50-mile

radii policy criteria for METRO and VRE station

areas. The story is, however, woefully weak with

respect to the history of METRO station-area

policy and action in the County.

This

level of citizen and political “leader”

support has not always been present. Support for

specific station-area, METRO-related development

was written into the Comprehensive Plan in the

70s but removed in the 80s. (See End

Note Five.)

Even

many of those who live near a METRO station and

do not want “transit-oriented development”

at their station agree that, in general,

METRO-supportive station-area development is a

good idea. Many think that station-area

development should be a monoculture but that is

also another story.

A

Different Vision

Given

the fact that the existing development in the

Centre of Greater Tysons Corner is nothing like

what existed when METRO came to the Centre of

the Federal District or to the Rosslyn-Ballston

Corridor, the “Four Billion Dollar Question”

is:

What

could be done in the Centre of Greater Tysons

Corner so that METRO on stilts does not look

like the current “photo simulation?

Let

us wipe the slate clean and consider a real

alternative to a tunnel or a naked track on

stilts in the median of a busy arterial.

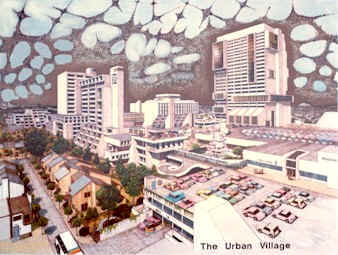

The

first image of a real station-area alternative

that I recall seeing was a low oblique

perspective of a multi-use, shared-vehicle

station-area termed “The Urban Village.”

It was drawn by Richard L. Thornton in the early

1970s. Rich was a recent Georgia Tech

graduate in architecture who worked with me at

RBA (nee, Richard Browne Assoc.) As I

recall, Rich’s sketch was drawn to illustrate

what a station area might look like in connection

with RBA’s bid to do design work on the East

Line of MARTA in the Atlanta New Urban Region. (For

background of this and related drawings by

Thornton See End

Note Six.)

Other

illustrations may have predated Thornton’s

drawing but his is the one that sticks in my

memory. The image was more complex – more

buildings, more architectural interest and

larger in scale – but had some of the flavor

of the Disney World Contemporary Hotel, which

had a monorail station in the lobby.

Thornton’s

drawing represented a fundamental shift from the

schematics that influenced the design of the

above- ground METRO stations in the National

Capital Subregion, the BART stations in the San

Francisco New Urban Region and later the MARTA

stations.

Rich’s

graphic was also dramatically different than the

recent renditions of “transit oriented

development” by New Urbanist designers. New

Urbanist drawings almost always have the station

located at the edge of a meadow or facing a

large plaza. (That is, if the station is not

underground along a boulevard that looks like

Champs Elysees.) The “town square”

station-area is a pleasing visual element and it

allows the transit operator to see their pride

and joy – the station and the train – front

and center across a greensward or plaza.

Architects

of all persuasions (and their clients) prefer to

show off their buildings fronting on a plaza or

other open space. Most of the graphics depicting

shared-vehicle stations (and the design of the

stations) are paid for by the shared-vehicle

system operator or by those who want to please

or impress the system operator.

On

the other hand, what shared-vehicle system

riders do not want when they step from the car

onto the platform is the prospect of a long

escalator to ride, a wide street to cross or a

long pedestrian bridge to navigate. They

especially do not look forward to a big plaza or

greensward to slog across – especially in hot,

cold or wet weather.

Most

riders got onto the system to travel to a

destination and that destination is not often a

park. If a park is the destination, then the

park should be a main use in the station area

such as the Montreal Zoo at the Angrignon

station. In most cases the open space should be

accessible but not take up the space between the

car door and the destinations of the majority of

the riders.

Marriott has for several

years advertised the redesigned of Courtyard by

Marriot hotels as being “designed by business

travelers, for business travelers.”

Shared-vehicle systems need to be designed by

system riders for system riders. If they were,

they would look more like Rich Thornton’s

drawing and less like a station in a park.

Pyramid

Strategy, Not a Pyramid Scheme

From

a distance a station-area should look like an

attractive, well-articulated “pyramid” with

the highest intensity of land use (and thus the

centroid of origins and destinations of travel)

close to the center where the platform is

located and with lower-intensity uses feathering

out from the center.

In

fact this is exactly what a shared-vehicle

system does under market conditions unless

governance land-use controls interfere. The

Montreal Metro was developed as a part of the

EXPO 67 (1967 Worlds Fair) initiative. We recall

looking out across the Centre of Montreal from the

roof of a downtown hotel just a few years after

the Metro system opened. By 1968, one could

already identify the locations of the stations

by the clusters of new buildings at the Metro

station sites. Now a visitor does not need a map

to follow the Metro lines when the Core of the

New Urban Region is viewed from Parc du

Mount-Royal. The same is true for the Subway in

Toronto when viewed from the CN Tower.

Both

Montreal and Toronto New Urban Regions have made

far better use of shared-vehicle systems in

shaping the urban fabric than have New Urban

Regions in US of A. For example a more

disaggregated pyramid form can be observed in

the aerial views of the Rosslyn–Ballston

Corridor found in Blueprint. A close examination

of a the Rosslyn–Ballston Corridor air photo

with .25 and .50 mile radii circles shows that

much of the prime access (aka, “front hook”)

area is taken up by streets. That is one reason

we have created the sketch plan process that

follows.

But,

first, an overarching station-area concept is

important to bear in mind: The METRO station

must be integrated into the surrounding urban

fabric. (For a survey of examples from Europe

and the US of A, see End

Note Seven.)

From the outset METRO has been

about “building a railroad” and not about

creating functional urban fabric. There are

thousands of examples from Wien to Vancouver and

from Oslo to Madrid where below-grade, at-grade

and above-grade stations could have been

improved and still could. It took a third of

century to finally start to cover the

escalators.

With all these shortcomings, the

worst mistake has been the failure to

accommodate the interest and need of METRO

passengers to access the places they are going

to into the design of the facilities.

Why

"Transit" Works

It

is important at this point to make it very clear

how and why high-capacity, shared-vehicle

systems support functional settlement patterns

in a METRO station area.

Shared-vehicle

systems do not provide access and mobility

because all those who live, work or seek

services and recreation in the station-area

jump on the train to meet their every travel

need.

Shared-vehicle

systems "work" because they support some

high-value trips for many who live, work

or seek services and recreation in the

station-area. By doing this, the shared-vehicle

system facilitates and serves patterns and

densities of land use that allows most

workers, residents and visitors to meet many of

their needs without resorting to any vehicle.

Many

“mode split” calculations intended to show

that transit only serves a small percentage of

the travel demand are bogus because they do not

address the ability of many in well functioning

station-areas to assemble a quality life without

using any vehicle.

Many residents can

prosper with an occasional vehicle rental, a

shared private vehicle (formal – zip car,

etc,. or informal) or at most one car per

household. Further, the autonomobile trips they

do take are often in off peak times and

directions. Beyond that, the vehicle storage

(parking) can be at the fringe of the station

area and does not disaggregate the critical,

synergistic elements of the station-area

settlement pattern.

In

summary: The flux of activity (aka, land use

density / intensity) supported by

high-capacity, shared-vehicle systems such as

METRO allow many “trips” that would

otherwise be vehicle trips to become “stops

on a pleasant walk.” The key here is

“pleasant.” More on that below.

The

requirement to meet a range of needs is why

station-area land use mix and “Balance” is

so important and why system-wide Balance of all

station-areas is required to maximize the

functionality of any shared-vehicle system.

These are the reasons a station area Pyramid

Strategy is so important.

A

Do-It-Yourself Sketch Plan Process for Readers

The

design and function of shared-vehicle system

station-areas are critically important because:

Functional

station areas are critically important because

Autonomobile- dominated settlement patterns are

dysfunctional and cannot provide mobility and

access for large New Urban Regions.

How

does one lay out a shared-vehicle

system-serviced Centre for Tysons Corner?

The

following is what every citizen should have

learned in grade school along with why it is

important to get enough exercise and sleep, eat

the right foods and avoid excess television and

video games. (The prerequisites of enough sleep,

good food and avoiding the illusion of escape

via television and games were laid out in Jim

Bacon’s column, "Brain

Games," on 2 April, 2007.)

Patrick

Kane has shown by his “Boom Town”

interactive game that fourth graders have the

experience and knowledge to intelligently lay

out Planned New Community components (and thus

shared-vehicle station-areas). They are

better equipped for this task than adults. In

fact, they are far more adept at creating

Balanced sketch plans than teams of

“professionals.”

Until

there is a revised public school system and a

well-informed staff in the Main-Stream Media you

are going to have to do the job yourself. Here

is the first of two sketch exercises:

The

18 February 2007 WaPo lead Metro Section story

headline reads: “Next

Stop, Tysons: Fairfax County Planners See

Ballston Neighborhood as Model for

Transit-Oriented Overhaul of Sprawling Business

Center.” The story by Alec MacGillis compares

Tysons Corner to the Rosslyn–Ballston

Corridor. (See End

Note Eight.) For now the important thing is

that the story includes a somewhat out-of-date

air photo of the Centre of Tysons Corner via

Google with the four proposed METRO stations

located.

The

following is a step by step walk-through of the

process that allows readers to create a

quantified sketch plan for the four Greater

Tysons Corner METRO stations. We could just

provide a graphic and go on but it is much more

effective if the reader does the drawing and the

calculations. We provide metrics to help guide

the process and our version of the exercise as

Graphic One in the Gallery at the back of the

End Notes.

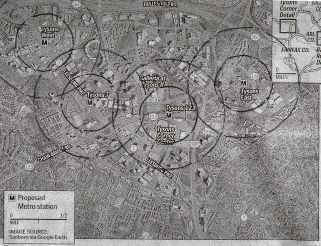

| Step

One: |

Go

to the print edition of the 18 Feb WaPo

story about Greater Tysons Corner and the

Rosslyn Ballston Corridor. Take the photo

of Greater Tysons Corner to the copy

machine and blow it up 200 percent. (In

the alternative, use the air photo at the

current scale with a magnifying glass.)

You can use any current air photo of

Tysons Corner and then locate the stations

from the WaPo story or other sources.

Using a map rather than an air photo will

distort the results due to factors

explored in Chapter 16 of the Shape of the

Future. |

| Step

Two: |

This

is the important part: Draw Circles with

.25 (1,320 feet) and .50 (2640 feet) radii

around the four stations. The R=.25 circle

contains 125 acres, the R=.50 circle

contains 500 acres. |

The

first thing you will notice is that much of the

land within .25 miles (1,320 ft.) of the station

platform is within public right-of-way. This

should set off alarm bells. Building a Four

Billion dollar METRO extension and then

reserving the land accessible to the most

important stations for roadway makes absolutely

no sense -- regardless of whether the train is

in a tunnel or on stilts.

The

second thing to note is that the existing

concentrations of buildings, e.g. those along

the Dulles Access Road, are some distance from

the stations. Many of the largest existing

buildings fall in the R= .50 mile circle and

many are more than .50 miles from any station.

This provides a glimpse of how much vacant and

underutilized land there is if the existing

right-of-way determines the METRO alignment. The

distance of the stations from concentrations of

trip ends is a result of letting roadway

alignments determine the track layout.

The

next step is to quantify the air photo with the

four bulls-eye station areas:

Get

out a calculator, a ruler and a blank sheet of

paper. To answer the question,

“How much land is in the public

right-of-way,” one needs a ruler and one

metric: There are 43,560 square feet in an acre

of land. Use a ruler and the scale of the map to

figure up how many square feet are in the

right-of-way. One can also figure up how much

private land outside the right-of-way is within

.25 miles and is vacant or underutilized.

To

answer the question, “How much building area

would this land support,” one needs an

additional metric: The Floor Area Ratio (FAR)

over the entire area within .25 miles of the

METRO platform (125 acres as noted above) might

rationally be pegged at 8.0 for a system with

METRO’s capacity.

To

answer the question, “How much is the building

area over public right-of-way worth,” one

needs an additional metric. An average value of

$300 per square foot of built space would be a

conservative benchmark.

The

totals may vary from reader to reader in this

sketch plan process depending on the assumed

location of the edge of the right-of-way. The

way we figure it, within .25 miles of the

platform at FAR 8, the potential exists to build

about 14 million square feet of space per

station, and with a pyramid configuration, about

six million square feet over the right-of-way at

each station. Most important is that all of

the most valuable space – the tallest part

of the pyramid – is located over public

right-of-way.

That

should be seen as a very good thing. The public

already owns land that will be much more

valuable when the public invests in a METRO

platform in the right of way. More on that

later.

To answer the last question, readers need

to decide how much a square foot of building is

worth. Today’s prices ($300 per finished square

foot) implies a value of $1.9 billion worth of

Class A space for each of the four stations. How

much would a knowledgeable developer pay for a

99-year lease to build six million square feet

over a public right of way adjacent to a METRO

platform? That will depend on what conditions

are put on the sale but it is a good guess that

it would be enough to pay for an extended

platform and for enhancements plus a

contribution to cover other capital costs of

extending METRO.

Before

we start counting the public revenue chickens,

there is one big constraint. The development

over public land for the four stations at FAR 8

totals over 24 million square feet, and within

.25 miles the total is more than 56 million

square feet. It will take years for the market

to adsorb that much space. All of Greater Tysons

Corner now totals in the neighborhood of 35 million

square feet of non-residential space.

From

our first sketch exercise we can conclude that

if we run METRO under or over VA Route 123 and

VA Route 7, there is a huge difference between

using or not using the land over the public

right-of-way.

So,

let us stop for a moment and consider what it

means for the public to own this land.

Public

Way Rights

The

term “air rights” carries unfortunate

connotations, as if the right to build over

public rights of way was something airy, or

lacking in substance. The expression also stirs

up Business-As-Usual forces, who go to great

lengths to discredit it. Accordingly, it seems

wise to coin a word that puts the focus on the

public interest. Henceforth, we call the right

to build over public rights-of-way “Public Way

Rights.”

Building

the area around METRO stations to optimum

density generates hostility from adjacent

landowners. While they are keenly aware

development over the public land would make

their own land more valuable eventually, they

would have to wait until a market materializes,

and the interest clock is running on their own

investment. One way to sweeten the pot for

adjacent owners is to give them a right of first

refusal and/or a density bonus if the public and

private land in any quadrant of a station-area

is developed as a single, phased project.

This

incentive was built into the 70s-era Fairfax

County Comprehensive Plan for the Vienna /

Fairfax / GMU station-area – and wiped out by

the actions of Del. Scott and Supervisor Hanley,

as noted in End Note Five.

The

reason readers have not heard much about Public

Way Rights in the discussion of rail-to-Dulles

is that Greater Tysons Corner land owners would

not benefit as quickly from METRO if the most

important station-area land was developed first.

These propertied interests have paid for

studies, made political contributions to

officials at the municipal and state levels,

funded much of the earlier “tax district”

phase of the Rail to Dulles effort as noted in

“Rail-To-Dulles

Realities,” and they funded

TysonsTunnel.org. They want pay-off sooner

rather than later.

One

cannot blame these parties for wanting to

build on their own vacant and underutilized

land. But this is where those elected to

represent the public need to step in to create

a balance of public and private interests.

Readers

also will not hear about Public Way Rights from

those who want to get the contract to build the

rail system because they would not make more

money from such a strategy. Indeed, under a

Public Way Rights arrangement, station-area

developers would play a key role at each station,

which might reduce the role of, and the payoff to,

the system builder.

Readers

will not hear about Public Way Rights from

governance practitioners because it is the land

owners and those who want to build the railroad

who make the political donations.

The

only constituency that would really benefit from

extensive use of Public Way Rights would be the

system riders and the general public, and they

do not yet understand why they should be

interested. That is why education and general

public understanding is so important. WaPo

has spilled a trainload of ink on Rail to Dulles

and,

still, most citizens have no clue what

their stake is in either Rail-to-Dulles or

Rail-to-Tysons.

The

bottom line is that Public Way Rights are a

key to access and mobility in Greater Tysons

Corner -- whether METRO is in a tunnel or on

stilts.

Development

over public rights of way provides far greater

“connectivity” between METRO and the places

the METRO riders want to go. “Connectivity”

is the term Patrick Kane has used in his

teaching, consulting and writing on Rail to

Dulles.

In

fact, Public Way Rights are not just a good idea

in Tysons Corner but in many other places as

well. We have noted elsewhere that the 45 acres

of potential Public Way Rights in the

Vienna/Fairfax/GMU station area would

accommodate all of the AOL and WorldCom campus

jobs as well as places where many workers could live and seek weekly

services. And that was when their buildings were

fully occupied.

Across

the US of A, some of the land best

located for urban uses is now devoted to

over-designed 1950s “cloverleaves” at 150

acres at a pop. (See End

Note Nine.)

To

Tunnel or Not to Tunnel

Now,

let us explore the question of a tunnel vs an

overhead METRO line: Take a look at photo in 13

March or the 31 March WaPo stories. It looks

bad, but if we hire an Italian engineer, paint

the stilts sky blue, plant a lot of trees...

No, cosmetics will not help.

The

first thing to do is look at the air photo and

the bulls-eyes in the first sketch exercise. It

is clear that with...

...there

would be very little naked elevated track visible.

This fact weakens the “eye-sore” argument.

(See End

Note Ten.)

Now,

let us turn to the real reason citizens will

ride the METRO extension to, from and between

stations in Greater Tysons Corner, and the

reason that a tunnel may not be as good as an

elevated line.

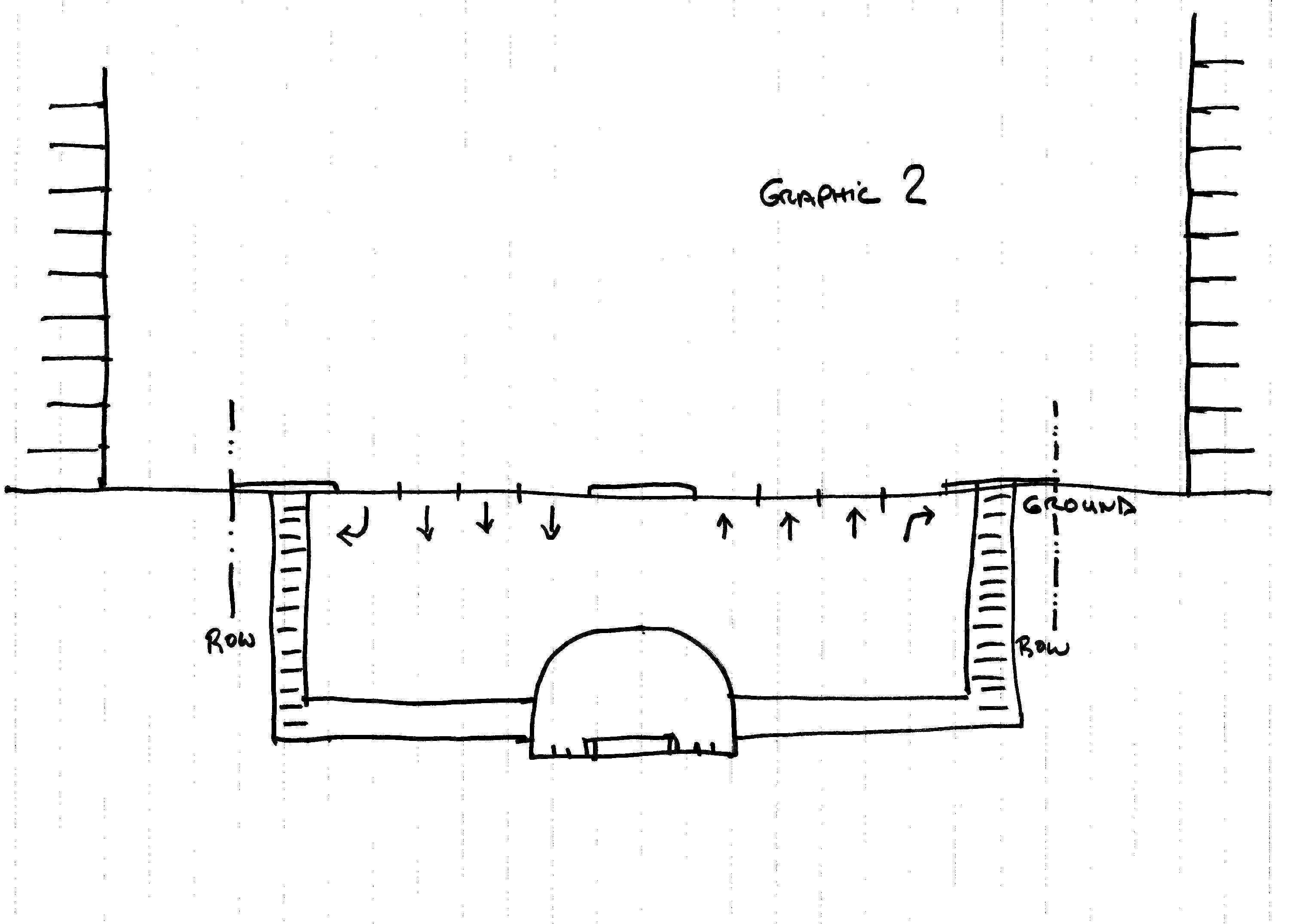

It

is time for more sketches: We provide our own

version of these sketches in Graphic

2, Graphic 3 and Graphic

4

in the Gallery at the end of the End Notes but

it is much more effective if readers do the

sketches themselves.

| Step

One: |

Take

out three pieces of lined tablet paper.

A legal pad works well for this exercise.

On the first sheet draw a vertical line

down the middle of the page, then turn the

paper to the “landscape” orientation

and label this line “ground.”

|

|

|

| Step

Two: |

Select

a scale for your sketch – 30 feet to the

inch works well because the distance

between the lines on a legal pad are about

10 feet at 30 feet-to-the-inch. This is

also the nominal distance from one floor

to another. Do not have a scale? Make one

by marking off the tablet lines widths on

a 3X5 card to create a 30-scale ruler in

10-foot increments.

|

|

|

| Step

Three: |

On

your first sheet, scale off 150 or 250

feet – the right of way for VA Route 123

and VA Route 7 varies through the Centre

of Tysons Corner. Now, in the middle of

the street go down 30 feet and draw an

archway representing the METRO tunnel at a

station with platforms.

|

|

|

| Step

Four: |

Next,

assume the same station design criteria

for underground stations as the existing

stations in the Rosslyn – Ballston

Corridor. (The streets in the R-B Corridor

are far narrower but we will get to that

in a moment.) Because most folks want to

exit the station on a sidewalk, not in the

median, draw tunnels to within 10 or 15

feet of the edge of the right-of-way and

then add escalators. Pause to envision the

fun one has walking in the pedestrian

tunnel under the street. (Hint, it is

similar to the walk from the station

platform to the plaza at the Courthouse

station.)

|

|

|

| Step

Five: |

Finally,

on this first sketch, go outside the right

of way five or 10 feet and sketch in the

buildings at 10 or 20 stories. Now, set

sketch aside for a moment.

|

|

|

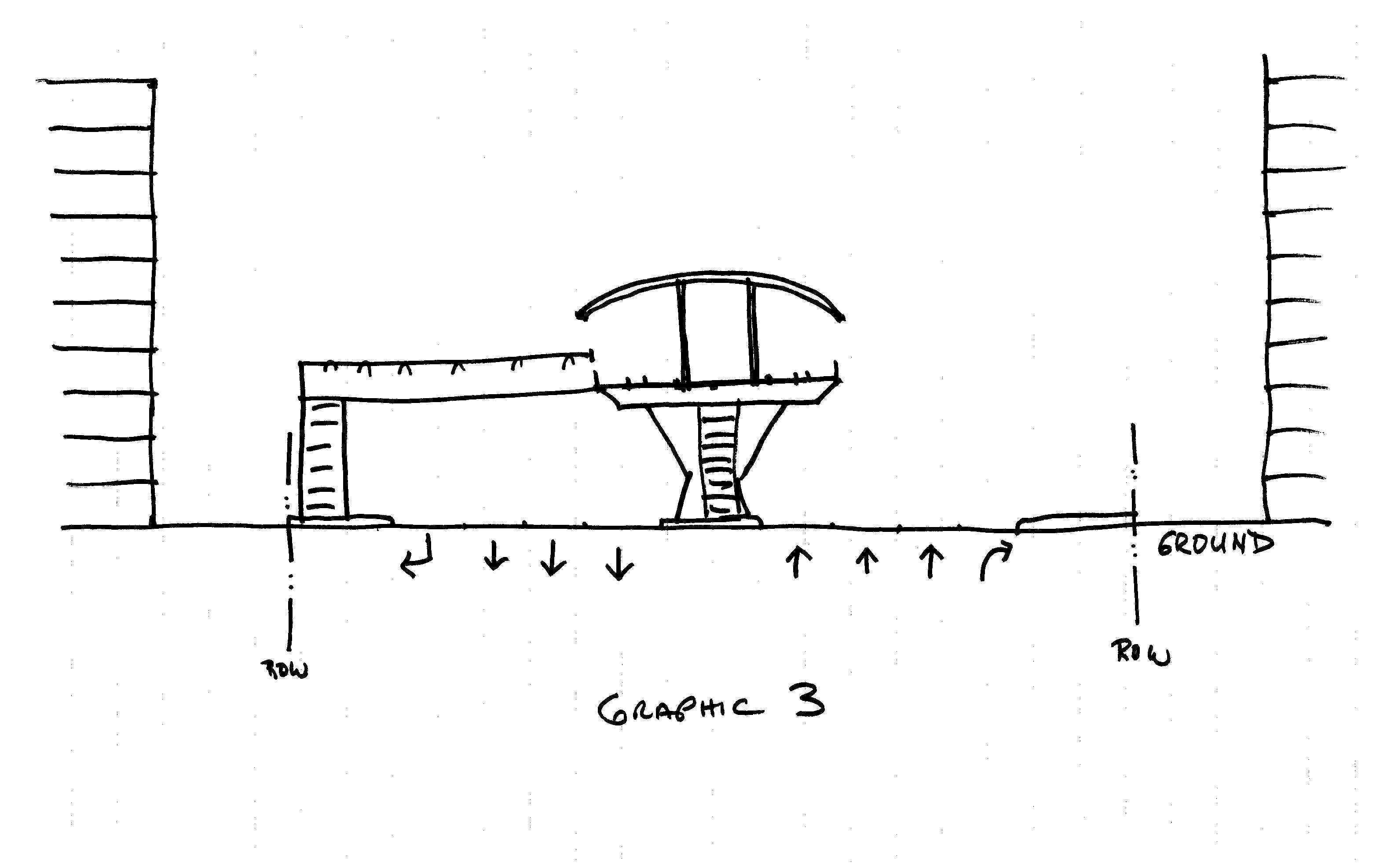

| Step

Six: |

On

the second sheet draw in the vertical

line, turn the paper to landscape

orientation and put in the roadway

right-of-way. Next locate the track level

30 feet in the air. Now sketch in the

track and station platform based on the

photo simulation that WaPo has published.

Next, add the stairs/ escalators over or

under the tracks to get from one platform

to the other and the cross-walks or

pedestrian bridges to get to the

sidewalks. Next, add the buildings. If you

want to be fancy, put in both ground and

elevated level entrances to the

buildings.

|

|

|

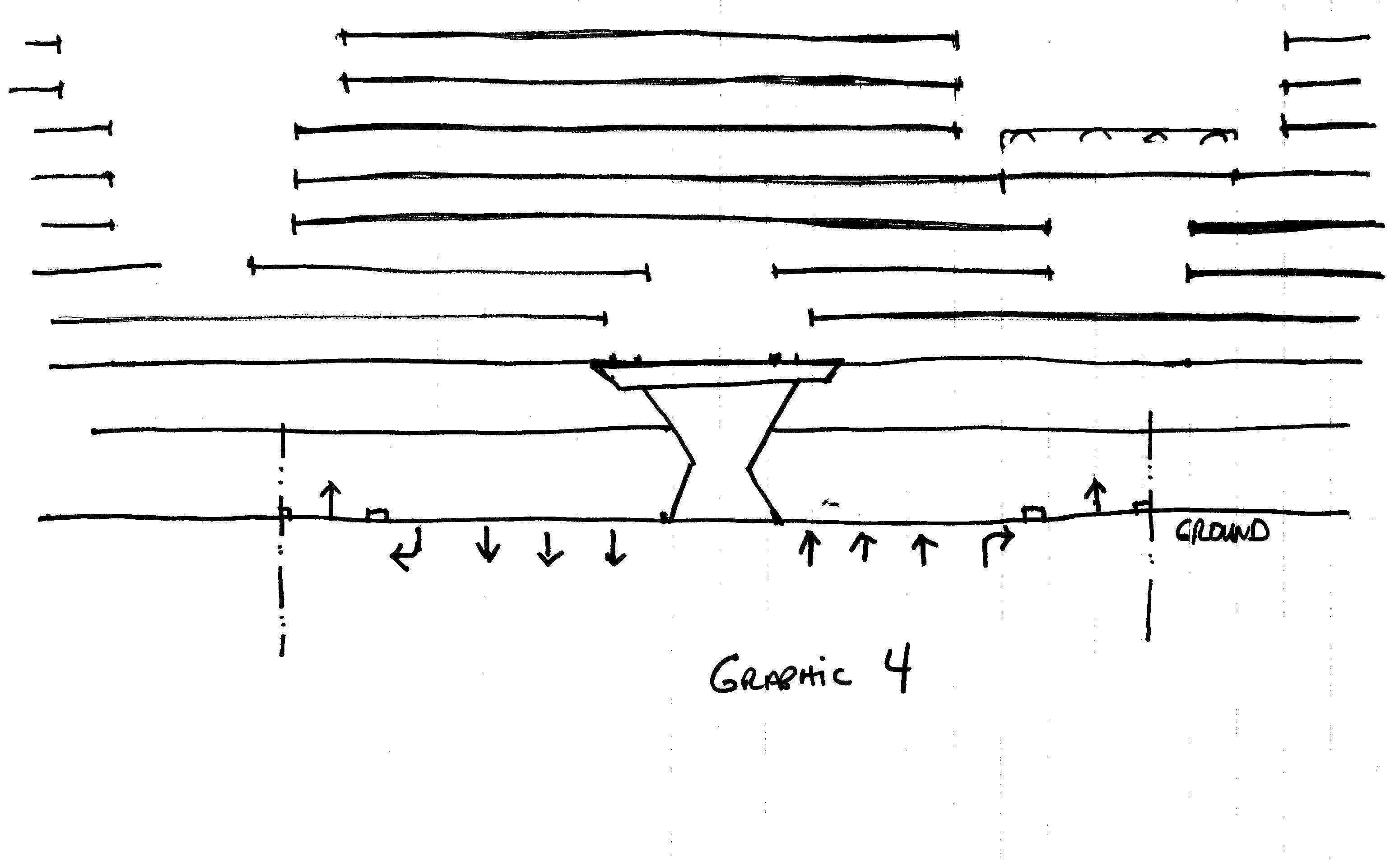

| Step

Seven: |

We

are almost done. Take the third sheet of

paper and follow the same steps as in Step

Six up to the track and station platform.

Next, draw horizontal lines every 10 feet

to represent the floors of a structure

built on air-rights over the right of way.

The lines can go all the way to the edge

of the paper. Now take an eraser and

create atria, walkways and plazas where

ever they will work well. The level

between the street and the platform can be

a service level for deliveries, storage,

and utilities.

(Parking

for the buildings, greatly reduced thanks

to METRO access, would be located off the

drawing in locations convenient to

surrounding streets, not from the arterial

that conflicts with the pedestrian

movements.) |

Now, let us assume you have a 10 a.m. meeting in

the building closest to the “Tysons 123"

station platform. Which sketch works best for

you? When citizens get on a shared-vehicle

system, it is not to joy ride but to get to

where they want or need to be. We know that the

closer to the car door the destination is, the

more likely citizens are to ride a

shared-vehicle system.

In

your diagrams, which scheme has the greatest

access to origins and destinations for

shared-vehicle system riders in the buildings

closest to the station platform?

If

one assumes a station-area pyramid of land-use

flux, which of the station area cross section

sketches serves the most riders and eliminates

the most need for Autonomobiles?

The

Magic One Quarter Mile

When

discussing station-area planning, one frequently

hears that .25 miles is a magic number and the

limit of shared-vehicle system impacts. Others

say some will walk farther but that “no-one”

will walk more than .50 miles. These arbitrary

numbers are silly. Distance and other barriers

of pedestrian travel in the station-area are

psychological as well as physical.

The

key to pedestrian travel is interest and

ability. Most will cross a street to be in

contact with their love interest. A few look

forward to a walk from Springer Mt., Ga., to Mt.

Katahdin, Me.

How

far a person is willing to walk depends on

interest, time, resources, and health/mobility.

The key for most walkers is to make the

station-area travel diverse, complex,

stimulating, but above all

interesting/satisfying and safe. For some that

requires higher levels a security/ safety, for

others higher levels of diversity, interest and

excitement. That is why a functional station

area must have a network of pathways that

provide a variety of alternative experiences and

a minimum of obstacles like wide streets, long

tunnels, long empty bridges, abrupt changes in

level, etc.

The

word “willing” in the phrase “willing to

walk” is also critical. In our years living

and working on small Caribbean islands, we

seldom found workers who would rather walk to

town, regardless of the spectacular scenery.

When they did, there was always someone or

something they hoped to encounter along the way.

The

same parameters, as we will see in Exercise Two,

apply to above or below ground. As with other

parameters we call The Natural Laws of Human

Settlement Pattern, the exact radial distance

from the station platform is not the issue. The

design of the station area should rely on three

factors. Functional station-area strategy is a

matter of:

-

Scale

-

Intensity

and Flux

-

Balance

Scale.

With respect to scale, if one uses a .50-mile

radii, then the Village Scale station-area is a

mile from edge to edge. It is not the station

platform alone that should be accessible but the

entire station area.

Intensity.

If there are 500 acres in the station-area (.50

mile radii) then one spreads out the uses and

there is a loss of connectivity, adjacency and

synergy. In terms of form for a large

station-area, think “mesa” rather than a

“pyramid.” A station-area of 500 acres at

higher intensity (2.5 vehicle trip ends per

square foot of ground) requires three system

stations with METRO capacity (or two stations

serving different systems) such as the Centre of

Paris served by Metro and RER.

Balance.

The big issue is Balance. The station area needs

to be large enough to have Alpha Village scale

diversity and small enough to have functional

access to the destinations needed to assemble a

quality life.

Mystique

of the Grid

Yes,

pedestrian spaces for strolling and sitting

along urbane “boulevards” can be attractive

in good weather. These amenities can be

accommodated in the Pyramid Strategy but they

would be on streets running perpendicular

to the METRO line. Before going whole hog for

sidewalk cafes, however, consider how many

people really like to sit along a boulevard

carrying as much traffic as VA Route 7,

especially when it is cold, hot or wet?

When

planning to introduce a new shared-vehicle

system, a grid is fine if the grid already

exists. The street and ownership pattern

provides an historical and psychological

orientation to the redevelopment that will

result from added access and mobility provided

by the public investment in a shared-vehicle

system as happened in the Rosslyn–Ballston

Corridor.

A

grid of streets is not a cure-all to solve

Tysons Corner access and mobility dysfunction.

What is important is a web of pedestrian

access, not streets to accommodate

Autonomobiles or roadways that are dominated

by Autonomobiles. (See comments in the

Bacon's Rebellion Blog “Ballston

on the Half Shell.”)

Public

Way Rights and Pyramid Strategy development can

create a grid of pedestrian access but it will

not be simple to design or cheap to build. Yes,

there can be tree-lined boulevards with sidewalk

cafes in some locations and, yes, ventilation

and sound deadening will be more expensive, and,

yes, views can be provided... (For further

exploration of the shortcomings of the grid, See

“Myth of the Grid” Sec X, # 5 in Handbook,

First Edition.)

The

bottom line is citizens are spending $4 billion

to build a system to get as many citizens as

possible from where they are to where they

want or need to go. It is clear that Public

Way Rights and Pyramid Strategy are the way to

go, be the rail line tunneled or elevated.

Unfortunately,

despite many examples of this sort of

development, these ideas will never see the

light of day in MainStream media because none of

those who have staff, hire consultants and

public relations spinners and write press

releases are interested in “solutions” that

are anything beyond Business As Usual.

Prize-Winning

Illustration

Exploration

of a fundamentally different station-area design

strategy brings out the dissenters just like air

rights and Henry George. (See End

Note Eleven.)

The

discussion of the Fundamental Changes to the

tunnel and the grid raises

many questions, among them are:

“Given

what you have learned from these two exercises,

how does one illustrate the wisdom of using the

land that citizens already own to support

evolution of functional settlement patterns

supported by the extended METRO system?"

“How

does one illustrate the shortsightedness of

insisting that a tunnel and a grid of streets is

the ‘only’ solution?”

The

recent award of the coveted Pritzker Prize in

Architecture to British architect Richard Rogers

inspired a possible way to put these questions

in context. The series of three sketches

outlined above were a first step.

Those

who have been to London (Lloyds of London

Building) or Paris (Georges Pompidou Centre) and

have seen Richard Rogers’ most highly regarded

buildings may guess where we are going. The

Lloyds of London Building which was designed to

fit an irregular lot in the heart of the

financial district in “The City” is the best

example for this illustration. In this

structure, Rogers pulled the elevators and the

stairwells out to the corners of the building

footprint. Pulling the elevators, stairs and

services to the corners rather than putting them

in core (center) of the floor plates, leaves the

entire floor open for an atrium and for maximum

flexibility of floor planning.

To

illustrate the silliness of a METRO of stilts

but with no Public Way Rights development,

assume that the Lloyds of London building was

located on a typical Tysons Corner building pad

and that Rogers had put the elevators, stairs

and other core functions not at the

building corners but in the middle of the

surrounding roadways. That is exactly what

putting METRO in a tunnel or on stilts without

Public Way Rights would do.

Think

of METRO as a express horizontal elevator. It

needs to have its stops near where the riders

want to be.

The

alternative is to put the station platform where

it looks best to the shared-vehicle system

architects and the system operators and serves

best the private land owners but leaves out

those who use and pay for the system, the METRO

riders and the general public. The current

trajectory will waste the $4 billion it will

cost to build the METRO extension because it

will leave the Autonomobile as the preferred way

to access buildings, goods and service in the

Centre of Greater Tysons Corner.

The

"Fixed Price" Is a Mirage

Other

issues need to be mentioned briefly in context

of Rail to Dulles.

The

idea that the “negotiating fixed price” is a

real “fixed price” is frightening. The facts

of the Dulles Transit Partners LLC “fixed

price” discussion

reminds us of a conversation we had in an

airport lounge with a well-to-do, 30-something

from Hollywood a few years ago. This is a

paraphrase of a 10 minute conversation about a

new house he was having built:

“We

have a fixed price with our builder. He will

charge us $1,273.95 for the front doors. We are

working with the builder and others as we go

along to tie down the other costs of our 5,900-square-foot-house

on an adobe hillside covered with manzanita

overlooking the ocean.”

The

Public Needs Help

There

is a long ways to go to get rail to Tysons and

then on to Dulles. Everyone must get on

the same train if there is to be any train, any

time soon. There is every reason for all to

agree. With Pyramid/Public Way Rights strategy, even

the adjacent land owners who will not make quite

as much money in the short run, will be much

better off in the long run. Bickering will

result in the demise of the Rail-to-Tysons and

Rail-to-Dulles efforts.

By

laying out the two sketch exercises, we hope to

have outlined a prototype tool for citizen

understanding and participation in the evolution

of human settlement pattern. Creation of these

tools requires time and effort that does not

forward the specific short-term interest of any

existing enterprise, agency or institution.

Preparation of such tools and carrying forward a

participatory public process is an important

role for a public architect / urban designer.

Most

regional and large municipal governance entities

in Europe have staffs to do this work. Most of

the large municipal governments in the US of A

do not have a public architect or an urban

design staff that focuses on the public interest

issues. “Planners” push paper and words.

They rely on private architects and designers

who are working for private or public clients to do the design work. Both have

similar “I want my structure or facility to be

seen, or better yet, to dominate the urbanscape”

perspectives. (See “The

Role of Municipal Planning in Creating

Dysfunctional Human Settlement Patterns.”)

Where

to From Here?

Politics

is broken and there is a critical need for

Fundamentally Change in governance structure.

This will happen only by getting politics and

governance out of the grasp of special interests

and political contributions, and by freeing

governance from the influence of widely held

Myths.

There

is also a critical need for Fundamental Change

in human settlement patterns. This will happen

only by getting the evolution of these patterns

out of the grasp of special interests and

political contributions, and by freeing

settlement patterns from the influence of widely

held Myths.

Freedom

of movement is not free, it comes at a cost.

Travel

takes interest and health for the short haul.

Travel

takes time and resources for longer

destinations. The farther you go and the faster

you want to travel the more resources it takes.

If wishes were horses, beggars would ride.

In

large New Urban Regions reliance on private

vehicles (Autonomobility) for more than a small

percentage of the trips is

an economic and ecological dead end. Autonomobility as expressed by

The Private Vehicle Mobility Myth violates the

laws of physics and economics and is the obverse

of reality.

The

word “Balance”

in “Balanced human settlement patterns”

means a configuration that suits the largest

number of citizens with the least expenditure of

time and resources.

Those

who live in a fantasy land and/or make money

from dysfunction hope citizens will not come to

understand reality before that make as much as

they can.

Citizens

are running out of time to make changes. An

intelligent strategy for Rail to Tysons and Rail

to Dulles would be a good place to start.

EMR

As

always, special thanks to all those who reviewed

and commented on the draft of this column.

--

April 16, 2007

End

Notes

(1).

The current proposal is for METRO to be extended

in Phase 1 from east of West Falls Church to the

Centre of Greater Tysons Corner and on to Wiehle

Avenue in Greater Reston. In Phase 2,

METRO is to be extended from Wiehle Avenue to

Dulles International Airport and on to Greater

Ashburn / Broadlands in eastern Loudoun

County.

(2).

In June 2004 we wrote “Rail-to-Dulles

Realities” concerning the inappropriate

boundaries of the then-proposed tax district to

support construction. We also examined the

interests of property owners, the benefits of

Public-Way-Rights and alternative shared-vehicle

systems.

In October 2004 in “Rethinking

METRO” we provided a new “foreword” to

round out a decade of analysis contained in “It

is Time to Fundamentally Rethink METRO,”

which was republished as a Backgrounder at the

same time.

In January 2005 we examined the

use of METRO and Commuter Rail as ways to solve

“The

Commuting Problem” and suggested that

there is no solution for “commuting.”

In May of 2006 we considered the alternatives to

traditional “heavy rail” and why

alternatives are not being seriously considered

in “The

Problem with ‘Mass’ Transit.”

Finally,

in September 2006 we castigated Governor Kaine

(“Two

Steps Backward”) for abandoning support

for the tunnel and what we believed at that time

to be the “only” way to ensure a functional

future of Greater Tysons Corner. We have now

reconsidered this position.

(3).

The press release (but not the WaPo

coverage) notes a “2,100 foot tunnel.”

In all likelihood this tunnel goes under the

highest point in the Centre of Greater Tysons

Corner where VA Route 123 and VA Route 7

interchange and this “tunnel” is not

associated with any station. A full Tysons

Corner tunnel would be about 3.5 miles (18,480

feet) long.

An earlier 9 March 2007 WaPo

Metro Section lead story set the stage.

The headline reads: “Tunnel at Tysons Would be

Costly Risk, Study Says: State-ordered Analysis

a Setback to Fairfax County Group Opposed to an

Aboveground Line.” This story, by Bill

Turque and Lena Sun, includes a rendering of an

elevated track in Greater Tysons Corner , which

will be the subject of the second phase of the

self-help design process outlined in this

column.

(4).

The original plan for METRO in the 1960s

considered ending the Orange Line at Tysons

Corner rather than at Vienna / Fairfax / GMU.

After review, Tysons Corner was considered to be

so auto-dominated that it had no potential to

become a supportive context for a shared-vehicle

system terminal. On the other hand, at the Vienna / Fairfax /

GMU site there were 800 acres of vacant and

underutilized land that could evolve into a

supportive Orange Line terminal station-area.

This decision was reconsidered and reaffirmed in

the 70s before the Orange line extension from

Ballston to Vienna / Fairfax / GMU was

started.

(5).

Former Fairfax Board member and current Virginia

Delegate Jim Scott as well as former Fairfax

Board member and later Chairperson and now

Secretary of the Commonwealth Kate Hanley

derailed METRO-supportive development in the

Vienna / Fairfax / GMU station area in the mid

80s. See End

Note Nine in “The Problem with ‘Mass’

Transit,” and “METRO West – 22 Years too

Late” at the Bacons Rebellion Blog.

(6).

Richard L. Thornton, AIA’s drawing is included

as Graphic 5 in the Gallery at the end of the

End Notes. Rich called his drawing “The Urban

Village.” (See Graphic 5.)

The term Urban Village became a

frequently used word in the late 1970s and early

80s, at the time we were planning the Fair Lakes

and participating in the 50 / 66 Fairfax Center

planning process. Richard is now practicing in

Talking Rock, Ga., and he was kind enough to

send along copy of the drawing that I recalled

from the early 70s.

When

I saw it again last week for the first time in

three decades, I was surprised that I had

recalled the perspective as being from a greater

distance. In the full-scale drawing, at the far left edge one can see the

“pyramid” of the next station-area. Many

similar drawings zoom in too close to show overall massing of the

pyramid form we discuss later. Designers

like to space out buildings for “light and

air” because clients want visibility.

Light and air is good but there needs to be a

balance with connectivity when station-area

planning is the issue.

I

am not the only person to recall Rich’s

drawings. In 1976, I left RBA to establish my

own firm and Rich left soon afterwards. He

went to work for the City of Atlanta on contract

while he earned a masters in city planning.

A primary focus of his work was to prepare the

urban design plans for the Midtown section of

Atlanta. His designs had the flavor of The

Urban Village drawing. The main building

in Midtown was the Bell South building over a

MARTA station, perhaps Atlanta’s best early

example of pyramid station area design.

The surrounding area was low-rise and seedy, as

we recall. Now, almost 30 years later

Midtown is part of Downtown Atlanta.

Rich

left the Atlanta area for 18 years and on return

was surprised to see development had followed

his early urban design sketches. Most of

the buildings shown on the urban design sketches

were hypothetical footprints. The architects who

designed the high-rise offices and apartments in

Midtown designed the real buildings to match

Rich’s footprints.

Rich

received an even greater surprise about two years

ago. There was a tract of land on the west side

of the Downtown Expressway just north of Georgia

Tech, which in the 1970s was occupied by

Atlantic Steel. The City of Atlanta wanted

the plant out of the Downtown area since it

produced a lot of toxic fumes. Officials asked

Rich to illustrate a mixed use - mid-rise

development in its place. Since his

contract was about to expire when they made the

request, he slightly modified The Urban Village

conceptual drawing to fit the Atlantic Steel

property. During the time he was away from

Atlanta, Atlantic Steel moved to Cartersville,

Ga., and the site sat empty for many years. In

the early part of this century, a consortium of

Atlanta interests redeveloped the Atlantic Steel

site and named it Atlantic Station. The finished project is easily recognized

from the drawing Rich did for RBA down to the

townhouses in the foreground with 1970s-style

architecture.

(7).

There are many station areas on high-capacity

shared vehicle systems such as Tunnelbanan,

Underground, Metro, U-Bahn and METRO that meet

some, but not all of the criteria for well

conceived Pyramid Strategy station-area design.

Here are a few which we recall off the top of

our head from 30 years of riding the

rails:

The

Tunnelbanan stations serving the Centres of

Planned New Communities in the Stockholm New

Urban Region such as Farstra, Vallingby and

Kiska exhibit many useful attributes.

The

Post WWII Planned New Communities in Great

Britain are beyond London Underground service

area but the 19th Century “suburban village"

Hampstead is a good example of the timeless

potential for urban-fabric regeneration in shared-vehicle station

areas.

The

Kaisermuhlen Station on the Wien U-Bahn serves a

pyramid of international agencies in the Vienna

International Centre but the station platform

itself is off set from the pyramid.

The

RER stations serving the planned expansion of

Paris in Marne La Valle are pyramid examples

that are visible from Tour Eiffel.

Scale

is an issue at both ends of the spectrum.

There are numerous examples of lower-capacity

systems (“commuter-rail,” trolleys,

“light-rail,” strassenbahns, etc.) serving

lower intensity areas that do not create

critical a mass of activity to result in

Balance.

At the other extreme, a good example of

over-sized station area development is La

Defense on the Paris Metro system. From a

distance, say the Arc de Triomphe, it seems to

be a pyramid but upon arrival one finds a huge

plaza and “ground level” that looks like a

set from a Start Wars movie not yet released.

The

Docklands in London is another bigger than one

station example. There is just one station on

the new Jubilee Line of the Underground but

there is also a horizontal elevator (Docklands

Light Railway) that connects Greenwich on the

south side of the Thames with four Docklands

stations and continues on to tie in with the

Underground near the Tower of London and St Mary

Stratford Bow church.

There

are examples in the US of A from which ideas

could be gleaned: The park in public-way-rights

over I-5 in Seattle. The elevated monorail

station attached to the multi-story Seattle

Center shopping and eating emporium built by the

Rouse Company.

Public

Way Rights

are used over Mass Pike in Boston. All of

Park Avenue in New York is over rail lines and

rail yards. There is a monorail station in

the lobby of the Contemporary Hotel at Disney

World. The list goes on and on and

includes examples of public-way-rights

development in Bethesda and plans for

development in the Rail-to-Dulles corridor.

Because of the enormous width of the Dulles

Airport Access Road (DAAR) right-of-way and the

fact that Reston was conceived of, designed and

viewed by residents as a single community on two

sides of an already existing limited access

highway, Reston has attracted a plethora of

public-way-rights schemes. We have

collected these over the years and two stand

out. One is by Patrick Kane, Guy Rando and

others and one by the architectural firm of

Davis and Carter. Both have strong points

but neither is a good example of a station-area

pyramid.

The

Kane / Rando scheme has buildings along the DAAR

from end to end, not concentrated at the

stations. The station platforms are in an

atrium and, in cross-section, the rail line is in the

bottom of a canyon with buildings terraced up

some distance away on both sides. One

drawing shows

a parking garage with parked cars having the

best view of the atrium. The drawings

illustrate 20 or

more buildings with from 4 to 6 million square

feet of built space but not focused on the

station platform.

The

Davis and Carter drawing depicts a cluster of

buildings at the Reston Avenue station area

directly over

the rail line and the public rights of way but

to show

off the buildings has the project surrounded by

looping ramps and access roads that would

isolate the mesa of buildings from the

surrounding land uses.

In

Tysons Corner itself, drawings by Davis and

Carter for the Tytran- sponsored exploration of

shared-vehicle oriented development by Patrick

Kane and others provides insight. Here the

intent is to show how infill could enhance a

site that is already among the most intensely developed

sections of Tysons

Corner just west of the Tysons II Mall. The

drawings illustrate an elevated elevator people

mover, perhaps assuming that METRO would be

located in the median of the DAAR.

The

best example off the top of our head is the

Nordwestzentrum station-area on the U-Bahn in

the Frankfurt Am Main New Urban Region (NUR).

Nordwestzentrum is on an extension of the

NUR’s U-Bahn. But this is an extension

with a twist. Instead of expanding

mindlessly into the periphery of the urban area,

this line takes a U turn and heads back toward

the Centroid to serve an area in a gore

between diverging radial U-Bahn lines.

Nordwestzentrum is an island of more intensive

urban land uses serving an already existing area

of lower intensity. The U-Bahn extension

runs in the median of a limited access roadway

but swings off the right-of-way to place a

station under a large superstructure that forms

the base of a pyramid of more intensive use.

Conceptually

Nordwestzentrum is first rate. In the

early execution it was not. When we were

working on the plans for Virginia Center, a

multi-use station-area development at what is

now the Vienna / Fairfax / GMU terminal station

of the METRO Orange Line, the Fairfax County

Planning Director, Sid Steele suggested that our

field work include a visit to Nordwestzentrum.

We

have slides from two visits in November 1984 and

December 1985. The combination of gray, New

Brutalist architecture, gray skies and dirty

snow recall frigid, uninspiring experiences.

When we were later in Frankfurt Am Main we did

not bother to visit. Through the wonders

of the Internet, you can Google

“Nordwestzentrum” and see what 20-plus years

of prosperity, new structures and sunny weather

can do to enhance the reality of a great idea.

(8).

When readers have completed reading this column

and the two-step sketch processes, they will be

able to critique the WaPo story of 18

February and identify why comparing Tysons

Corner and the Rosslyn– Ballston Corridor is a

red herring.

(9).

Public Way Rights are a good idea in many

places. Over the past five decades

Autonomobility advocates and their facilitators

have rammed over-designed limited access

highways and wide primary arterials through

thousands of Neighborhoods. (See "Interstate

Crimes," 28 February, 2005.) These roadways

have shattered Beta Neighborhoods into

dysfunctional Beta Clusters and Beta Dooryards

instead of uniting them into Alpha Neighborhoods

and Alpha Villages. These disaggregated

Beta Neighborhoods are home to millions of

citizens in Beta Communities with 100s of

millions of citizens. Instead of wasting

$Billions “rebuilding” Iraq, why not use a

carbon tax to build strategically located

air-rights platforms to reconnect the urban

fabric of the US of A in locations where access

and existing fabric create the market and

support for revitalization and reaggregation of

the settlement pattern?

(10).

Some have suggested that a

“benefit” of the elevated line would be the

“view from a train.” However, not many

shared-vehicle riders are thrilled by views from

a car window on an elevated line. Shared-

vehicle system riders are, in general, in a

hurry to get somewhere. Occasionally, there

exceptional views, such as those from the

bridges on Stockholm’s Tunnelbanan. To

the extent views are desirable, even with

Pyramid Strategy development, views could be

incorporated. But “the view from the train”

should not be used as makeup for the porker.

(11).

During a recent multi-party mass email exchange

on the deplorable state of the “recovery”

efforts following hurricane Katrina, we

witnessed the rejection of mild support for

Fundamental Change offered by Paul Spreigegen

the author of the landmark 1965 book, “Urban

Design: The Architecture of Towns and Cities.”

See "Down

Memory Lane With Katrina.”

Gallery

Graphic

1: WaPo Air photo of the Centre

of Tysons Corner showing the four METRO stations

with .25 and .50 radii around each station

superimposed.

Graphic

2: Underground

rail scenario

Graphic

3: Above ground

scenario

Graphic

4: Pyramid Strategy with Public Way

Rights scenario.

Graphic

5: Richard L. Thornton rendering

|