|

The

proposed extension of the Washington METRO system to Dulles Airport is one of the most expensive

infrastructure projects ever conceived in the state

of Virginia. The projected cost is $4 billion,

assuming no expensive delays or overruns. "Rail

to Dulles," as the project is known in

shorthand, is vitally necessary for the economic

health of Northern Virginia. But, as currently

conceived, the project would precipitate a

multibillion- dollar transfer of wealth from

taxpayers and commuters to politically powerful land

owners.

The

plan for financing Rail to Dulles has three main

components: The federal government will pay 50

percent, the state will pony up 25 percent, while

Fairfax County, Loudoun County and the Metropolitan

Washington Airports Authority will chip in the other

25 percent.

Where

will the state get its $1 billion share of the

money? From the commuters who drive along the Dulles

Toll Road -- commuters who had been promised that

the tolls would be scrapped once the original

construction bonds had been paid off.

And

who will benefit from Rail to Dulles? Commuters will

receive some benefit, to be sure, in the form of

reduced congestion. The METRO line, which will run

down the Toll Road right of way, will divert some

traffic from the highway to rail cars. But the

biggest winners will be the owners of land near the

11 new rail stations.

To

get an idea of how much wealth will be created by

Rail to Dulles, consider this: The current assessed

value of the commercial property in just the Phase 1

special tax district, concentrated in Tysons Corner,

is $9 billion to $10 billion.

Fairfax County is contemplating changes to its

comprehensive plan that would increase allowable

square footage of non-residential development

(offices, retail, hotels) by 43 percent and

residential development by 151 percent.(1)

Those zoning

changes in Tysons Corner potentially could translate into an

additional $4 billion in property assessments. And that

doesn't include the boost to property

within walking distance of the METRO stations, which

could easily double in value.

Add

it all up, and the increase in property values for just

Tysons Corner could well exceed $5 billion. But

the contribution of commercial property owners to

Phase 1 METRO financing would be capped at $400 million.

The

mismatch between property owners' contributions to

financing Rail to Dulles and the benefits they can

anticipate receiving are unconscionable. How

Republicans, who supposedly abhor government

giveaways, can tolerate such a lopsided distribution

of benefits is beyond

me. That Democrats, who purportedly believe in

transferring wealth from the wealthy to the poor -- not the

reverse -- can

countenance this arrangement is even more of a

mystery.

Rail

to Dulles has so much bureaucratic momentum behind

it, however, that it may be impossible to derail.

Suggestions that a Bus Rapid Transit system could

provide comparable mobility at a fraction of the

cost(2) have been swept aside. And, as intriguing as

the concept is, Personal Rapid Transit, a

21st-century permutation of mass transit(3), is still too

untested and unproven to gain popular support within

a politically acceptable time frame.

Given

the political realities that something must be done

now, and it must be done within the broad framework

already in place, there are two key points I

would emphasize:

First,

Rail-to-Dulles must be built. The project is crucial

to the economic vitality of Northern Virginia for

two reasons: (a) It will relieve traffic congestion

by taking thousands of cars off the region's roads,

and (b) it will provide the impetus to re-fashion

Tyson's Corner from the jumbled mess that it is now

into a world-class, transit- and pedestrian-oriented business

center.

Second,

sufficient economic value will be created that

everyone can come out a winner. There is no need to

plunder the mostly middle-class commuters who ride

the Dulles Toll Road. The tools exist to make

commercial property owners pay the full cost of the

project and still come out ahead.

Tysons

Corner is the most important business center in

Virginia. It accounts for more economic activity

than downtown Richmond, downtown Norfolk or even the

burgeoning Reston-Herndon technology center to the

west. The concentration of technology expertise,

human capital and entrepreneurial ferment has few peers around the country.

In

a testament to its business vitality, Tysons

prospers in spite of its grave flaws as a locus of

urban activity. Although

individual buildings may have architectural flair,

the business district is an aesthetic disaster. Visually, there are few memorable vistas or

focal points. A flotsam of mid-rise

buildings is awash in expansive parking lots, and

development is bifurcated by streets designed to move cars, not

people. Functionally, there is no pedestrian life:

It's easier to cross the street by driving from one

parking lot to the next than to make the trip on

foot.

Perhaps

most serious of all, there is a massive imbalance

between commercial and residential development. As a

consequence, tens of thousands of employees converge

on Tysons every morning from around the region,

adding immeasurably to traffic congestion in the

business center itself and the arteries leading

into it.

Addressing

these deficiencies, even in part, could create a

world-class business district. However, a makeover

will cost billions of dollars. Extending METRO

through Tysons Corner is the only way that would

stimulate the level of investment required.

|

|

Under

existing plans, the Rail-to-Dulles extension

would tie into the Washington METRO line near

the West Falls Church station on the orange

line. It would run north to Tysons Corner and

then hook up with |

the

Dulles Toll Road. In Phase 1, a $1.8 billion

project, the METRO would extend as far as Wiehle

Ave. on the eastern fringe of Reston.

In

Phase 2, the METRO would thrust past the employment

centers of Reston and Herndon, loop down to Dulles

Airport, and then continue west into Loudoun County.

In total, eight stations would reside in Fairfax

County, one in Dulles Airport and two in Loudoun

County.

The

first benefit to Northern Virginia would be

congestion relief. Rail

boosters assert that peak hour capacity would

equal four new lanes on the Dulles Toll Road,

accounting for an estimated ridership of 35,000 to

38,000 daily boardings. (Assuming most passengers

account for two daily boardings, one each way, that

would translate into 17,500 to 19,000 passengers per

day.)

That

aspect of the plan has gotten most of the attention

-- down here in Richmond, at least. But

equally significant, perhaps more so, are the

changes to Tysons Corner land use. The high-density

development that would cluster around the four METRO

stations would be so profitable that developers

could afford to bulldoze many existing

buildings, parking lots, side streets and related

infrastructure and rebuild the urban fabric from

scratch.

As

just one example of what could be in store for

Tysons Corner, consider Tysons Corner Center, a

project of the Macerich Company. Macerich, a

California-based Real Estate Investment Trust, is

one of the largest owner/ operators of regional

malls in the country. With anchor tenants such as

Nordstrom, Bloomingdale’s, Hecht’s and Lord

& Taylor, Tysons Corner Center, located on Rt.

123, is one of the largest malls in the Washington

metro area.

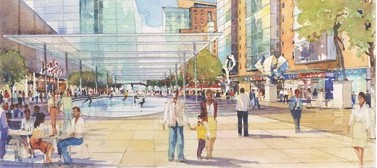

Rendering

taken from the www.tysonsfuture.com

website.

Under

the Macerich plan, the mall would remain in place,

but the land around it -- including a Circuit City

store and acres of parking lots -- would be

transformed. The company's ambition is to create

"a world-class community around the center

where people can live, work, walk and shop in a

vibrant, connected neighborhood." Plans call

for adding:

-

Four

office buildings containing 1.4 million square

feet

-

Four

residential buildings offering up to 1,250 new

units

-

A

240-room hotel

-

Street-level

restaurants and retail adding up to 200,000

square feet

-

An

ice rink, plaza, courtyards, water fountains,

performance stage, sky terrace and public art.

As

a mixed-use, "transit oriented

development," Tysons Corner Center would plug

directly into a Metro Rail station. Macerich would

make improvements to Rt. 7 and Rt. 123, and it would

provide connectivity by means of sidewalks, bike

paths, walkways and

improved bus/shuttle service. In marked contrast to

the auto-centric pattern of development that exists

now, this new community would encourage people not

only to use the METRO but to walk, bicycle, take

shuttles and ride buses -- eliminating thousands

more automobile trips every day.

Rendering

taken from the www.tysonsfuture.com

website.

One

of the most ambitious projects on the Fairfax County

drawing boards, Tysons Corner Center exemplifies the

grandiose scale of the redevelopment that could take

place, transforming Tysons Corner beyond

recognition. Given the square footage that would be

added by the zoning changes under discussion, Tysons

could accommodate another dozen Macerich-scale

projects. Rail to Dulles would catalyze billions

of dollars of real estate investment over a 10-

to 20-year period. The economic development

potential is breath-taking.

As

spectacular as the benefits of transit-intensive

development would be for Fairfax County, the positive

impact would ripple across Northern Virginia -- even

beyond the metropolitan fringe. The 12,500 housing

units built in Tysons Corner -- providing shelter

for some 25,000 residents -- would not have

to be built in Fauquier County, Stafford County or

western Loudoun County.

I cannot emphasize enough: The only way to prevent

hop-scotch, disconnected, low-density development on

the metropolitan periphery, where such development

is expensive, disruptive and unwanted, is to create more compact, densely

settled communities in metro Washington's core

jurisdictions. (The same logic applies on a lesser

scale to metropolitan Richmond and Hampton Roads.)

In

sum, Rail to Dulles is crucial to the future not

only of Fairfax and Loudoun Counties but to all of

Northern Virginia and all the counties in its

economic orbit.

But as much as the initiatives like

Tysons Corner Center should be encouraged, it would

near-criminal folly for state and county policy

makers allow landowners like Macerich to reap 90

percent of the economic value created by

construction of the rail line paid for with 90

percent public funds.

In

an ideal world, it would

be possible

to finance the construction of Rail to Dulles without

creating massive transfers of wealth to rich

landowners. Here's a schematic outline of how it can

be done if special-interest politics doesn't interfere.

First

some background: Fairfax

County has established a special tax district that

allows the County to levy an additional tax -- $0.22

per $100 of assessed value -- on commercial property

owners within the district. That rate could increase a few

pennies, but under no circumstance can it exceed

$0.40 per $100 annually. Furthermore, the

total tax obligation is capped at $400 million. As

things now stand, that is the full liability of

property owners for Phase 1 of the project.

Not

all landowners will come out ahead under the current

financing scenario. Those whose properties are

located closest to METRO stations will see the

greatest increase in value, while those located more

than a half mile distant will see only marginal

increases in value. Some landowners will get

fabulously rich from METRO while others will get

very little from it. Yet everyone within the tax

district would pay on the same basis. Bottom line: The tax

district is an engine of inequity

and it needs to be deep-sixed.

But

first things first. Before creating a new tax

district, Fairfax and Loudoun County planners need

to figure out what kind of land use they want around

their METRO stops. I would argue that the counties'

comprehensive plans should permit extremely high

densities above the METRO stations, should tone down

the density within a 1/4-mile walking distance, and should let densities taper off at greater

distances. In effect, there would be a central,

high-density point at each METRO station surrounded by concentric rings of

diminishing density, modified by geographical

features such as streams, gullies, major

thoroughfares, existing town centers and the like.

Then,

and only then, would planners configure Community

Development Authorities (CDAs) over the high-density

zones. The CDAs would have the power to issue bonds

to pay for their share of the METRO stations, rail

line, parking decks and other improvements required

to enhance the accessibility of the stations.

Landowners

near the METRO stations would get a giant two-fer from this arrangement: (1)

a massive increase in permitted density, and (2)

proximity to a METRO station. Spread across 11 METRO

stations, the real-estate value added

would amount to billions of dollars.

Under

the cost-sharing formula now in place, state and

local authorities will have to pick up a total of

$2 billion -- perhaps more in the event of cost

overruns or design changes such as running the

Tysons METRO line underground. If the debt were

spread across 11 stations, each CDA would need to

issue on average about $200 million in bonds. The

annual debt service on 30-year notes would be, in

very rough numbers, about $10 million per year.

To

pay off the bonds, planners

then would superimpose special tax districts over

the CDAs. Under this arrangement, only the landowners who benefited most

directly from the public improvements would be

forced to pay the special tax. Landowners outside a

1/4-mile to 1/2-mile radius, who enjoy neither increased density

nor proximity to METRO stations, would not pay the

higher tax rate. Commuters using the Dulles Toll

Road, who have already paid for construction of

their highway, would not have to continue paying

tolls to fund construction of the METRO as well.

(Maintaining tolls may be justified as a means to

continue funding improvements to the toll road, but

that's a different issue.)

Ideally,

the CDAs and tax districts would be structured to

ensure that nobody loses and everybody wins: Those

who pay the taxes would be more than compensated by

the soaring economic value of their property and the

returns they could generate from it.

As long as

their riches aren't coming at the expense of someone

else, I have no problem with landowners like

Macerich Company making loads and loads of money.

That's capitalism, baby! You gotta love it. But if

their riches come at the expense of other landowners

and powerless commuters, I have a huge problem.

That's state-sanctioned theft.

The

Kaine administration undoubtedly feels under

pressure to get the project moving -- that's why it

turned over responsibility for the project to the

Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. Finding

an alternative to the current, patently unjust

funding formula could delay the project for months,

so I don't imagine that the people in charge have

any appetite for

reopening discussions. But if the Kaine crew

stumbles blindly ahead on its current course, it will play Robin Hood in reverse:

robbing middle class commuters and giving to the rich and

powerful. Among voters, there will be far more

losers than winners, and they may find a voice come

election time.

--

May 15, 2006

Footnotes

1.

These numbers come from a Fairfax County

planning department PowerPoint presentation. See the

tables on page 19 of the document.

2.

See William Vincent's column, "Three

Big Ideas," Jan. 16, 2006.

3.

See Ed

Risse's column, "The

Problem with 'Mass' Transit," May 15, 2006

|